#HelloHyde Erases My Lived Experience

#HelloHyde seeks to celebrate the supposed one million lives “saved” by denying low-income individuals with Medicaid insurance access to abortion care. As the product of an unplanned pregnancy, I find this goal to be offensive, malicious, and enraging.

As abortion access advocates have made a renewed push this fall to end the Hyde Amendment on its 40th anniversary, anti-choice groups have been waging a campaign of their own. Organized by Secular Pro-Life, whose mission is “to end elective abortion,” #HelloHyde seeks to celebrate the supposed one million lives “saved” by denying low-income individuals with Medicaid insurance access to abortion care.

Among the goals of the campaign are to “expand the Hyde Amendment to cover children in every state and children conceived through violence, and cut the abortion industry off from all sources of taxpayer funding (not just Medicaid).”

The group asserts that “the Hyde Amendment caused between 18% (1 in 5.5) and 37% (1 in 2.7)” of women on Medicaid to give birth instead of receiving abortion care, which means around one in four people on Medicaid who are pregnant and don’t want to be are forced to carry to term against their will. I was only pregnant for nine weeks as a 30-something woman with access to health care and it felt like my body had been invaded; every day was a hormone-fluctuating, headachy, exhausted nightmare. Secular Pro-Life wants as many people as possible to go through that experience.

On a personal level, as the product of an unplanned pregnancy, I find this goal to be offensive, malicious, and enraging. I am not celebrating a policy that has harmed millions of people or a campaign that erases the lived experiences of my family.

The longer I work in reproductive health advocacy—fighting to expand abortion access specifically—the more I understand what a sacrifice my birth mother made and what she possibly has gone through since giving birth to me. Should I someday have the resources to find her (adoptions were almost all very closed with records permanently sealed in the 1970s), I would want her to know that I honor her pain and her love—and that I’m going to spend the rest of my life working to ensure as few people as possible endure what she went through.

***

I was conceived in 1978, just two years after Hyde was first attached to the federal budget by a legislator who readily admitted he “would certainly like to prevent, if I could legally, anybody having an abortion.” Apparently, he settled for denying Medicaid recipients access to basic health care for politically convenient reasons.

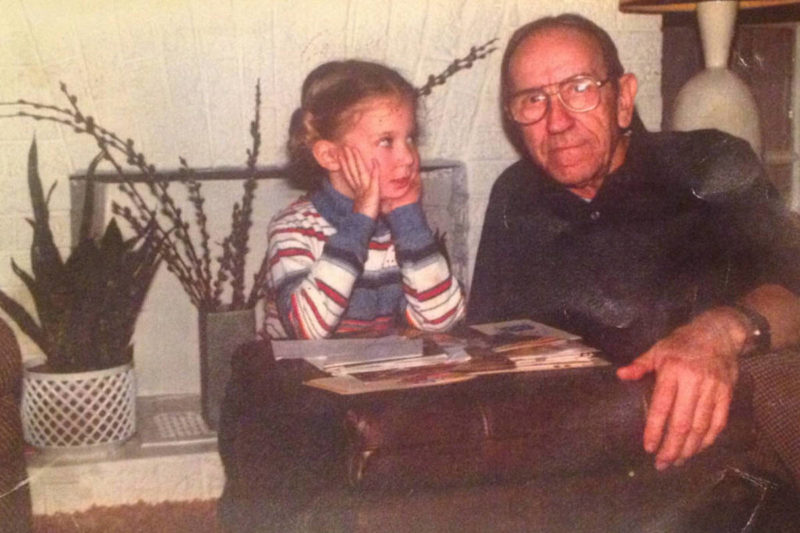

As my adoptive parents have told me over the years, my birth mother was a teenager living in the small, very religious town next to the one in rural Indiana where I grew up. She would have been finishing the first semester of her senior year when she found out she was pregnant, and graduated at a visible seven months along. Medicaid would have been the only avenue to health care for her and the likelihood that she would have had a sympathetic adult to turn to is heartbreakingly slim. Just five years after Roe v. Wade decriminalized abortion, it would have been at least as hard—if not harder—to find a provider in northern Indiana as it is today. (Thanks to all manner of omnibus anti-abortion laws and systematic defunding of clinics, including the Planned Parenthood locations that didn’t provide abortion care, only four of Indiana’s 92 counties have a provider.)

I have pictured my birth mother thousands of times over the years as my parents recited the bedtime story of the day I came into their lives. I’m told she was tall like me and blue-eyed like me. “She wanted you to have a better life than she could give you, so she gave you to us to love and take care of,” my adoptive mother would say. The natural skepticism built into my DNA sparked a curious hopefulness about whether that was true around the time I learned Santa Claus wasn’t real at age 8 or 9. I got confirmation that she definitely cared about my well-being in middle school when a letter from her was sent to my adoptive parents through the welfare agency that handled my adoption. She wasn’t with my birth father anymore—by all accounts my adoptive mother researched later, he was not the nicest guy. News travels in small towns, however, and she had heard he died from a rare genetic disease. (Wilson’s disease affects one in 30,000 people and causes copper to collect in the body, leading to a combination of liver disease and neurological and psychiatric problems.)

My birth mother wanted to make sure we knew so I could be tested—a very invasive, extensive, rough process in 1990, back before genetic testing. As traumatizing as it was to find out at 12 years old that I might die before I turned 30, the questions created by my self-doubt about whether she cared about me were settled. It’s quite an extraordinary thing to reach out to the people raising the child you gave up so many years before.

As reported at Rewire two years ago by Randie Bencanann, the co-director of an adoption agency, a study by the Child Welfare Information Gateway found that “three-quarters of birth mothers still experienced feelings of loss 12 to 20 years after placing their newborns.” While pervasive “abortion regret” is a myth (less than 5 percent of people report regretting the decision to terminate a pregnancy), adoption regret and related difficulties are very common.

It cannot be said enough that adoption is not an alternative to an unplanned pregnancy; however, it is an alternative to parenting. Bencanann reports that the majority of her clients were “too late for an abortion, didn’t know where to get one, or didn’t have the money to cover the cost.” They didn’t want to be pregnant, but they were unable to access a procedure to relieve them of the burden they carried.

Before I knew enough to have an evidence-based position about abortion, I was briefly “pro-life” as a religious teenager. I saw my status as an adopted child as indisputable reasoning supporting my position. “My mother could have aborted me,” I’d say calmly, but firmly, to people at my college who wanted to debate the concept of abortion in theory. “I wouldn’t be here,” I would add, giving a flesh-and-bone example of the potential harm done by abortion that rendered most of my friends speechless. I patted myself on the back for the mic-drop moment.

But that was almost 20 years ago. I’ve grown up a lot since then. In the decade between graduating college and getting into advocacy work I learned what life is like when you don’t have monetary or human support resources. I learned what it’s like to be in an abusive relationship. I learned what it’s like to get pregnant knowing that you could never, ever let that person become a parent. These days when I think of my birth mother, I wish I could hug her rather than the understandable, yet juvenile desire to be hugged by her. The more I learn about what people who give a child away go through, the more intense that desire becomes.

Bencanann described in her Rewire article what it’s like to assist those who end up in her office:

It was very difficult to watch these women go through the adoption process: undergoing nine months of pregnancy, withstanding inquiries from family or acquaintances about their plans for a baby, allowing near-strangers or people they had only come to know in the last few months to love and nurture their child, and then trusting those people to follow through on post-placement contact agreements. Some women were, and are, able to get solace from providing a good home for their child and giving joy to new parents. Even so, though, the process also nearly always involved anxiety and long-term sadness.

My heart regularly grieves for my birth mother. Campaigns like #HelloHyde attempt to erase all of that pain, and also all of the strength it took for my birth mother to be pregnant all those months seemingly without help. My adoptive mother was able to find out a great deal about my birth father after he died, and it’s highly likely that saving me from an abusive father was on my birth mother’s young mind. What a burden to carry, along with me.

We don’t support the victims of intimate partner violence in this country and teenagers are the most at risk. According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (NCADV), 20.9 percent of female high school students report being physically and/or sexually abused by someone they’re dating—and they have almost zero legal resources available to them. An NCADV fact sheet explains:

Federal law and many state laws define domestic violence as abuse perpetrated by a current or former spouse, co-habitant, or co-parent. This leaves dating partners without protections afforded to other current or former intimate partners, including access to protective orders and protection from gun violence.

Here, again, my birth mother was likely without options. And #HelloHyde would have us celebrate that I was conceived in violence.

Our society also doesn’t support parenting teens, choosing to shame them instead. I can’t begin to imagine the level of shame imposed on my birth mother in such a conservative religious community almost four decades ago. In addition to concerns about my birth father, it’s likely she either realized she wouldn’t have enough support to parent me herself or never even considered it because of the stigma around teen parenting. I certainly didn’t question that part of my bedtime story. “She was too young,” I heard thousands of times. Maybe she wanted to keep me? I may never know.

Suggesting we celebrate Hyde is also a rather racist proposition. Hyde is more likely to force women of color to give birth often against their will, as they are disproportionately in need of Medicaid coverage thanks to the ongoing structural inequalities in our country. Thirty percent of Black women and 24 percent of Latinas ages 15-to-44 are enrolled in Medicaid, compared with 14 percent of white women, according to the Guttmacher Institute. The first woman to die because of Hyde was a Latina—Rosie Jimenez. The undocumented community is hit particularly hard because of an almost utter lack of access to any legal resources.

My recent need to revise my adoption story thanks to a revelation from my cousin that my adoptive mom was insistent they adopt a newborn that was “female, all white” has confirmed that this nationwide statistic held true even in my rather white town during the time my birth mother was pregnant. It took nearly ten years for my adoptive parents to be matched with me because of her ethnicity restriction; they could have adopted rather quickly had she been more inclusive on the application.

***

I am indescribably grateful to my birth mother. But the reasons have changed over my life as I have gained empathy for the immense challenges she faced and what she likely continues to go through even today. My once-simple, “I’m so glad she chose to give me life when she had other options” teenage thought has grown complicated as I’ve grieved for her. I’m not convinced she had a choice. It’s so probable that she didn’t—or at least she felt as though she didn’t—that I can’t think about her without crying.

The story of my life is so much more complicated than the narrative #HelloHyde would paint. Twisting it to fit into their oppressive campaign to expand the harm done by the Hyde Amendment is a violent erasure that adds to my trauma and possibly hers as well.

I have come to terms with the cognitive dissonance of wishing my mother had a real choice to do what was best for her while knowing that could easily have meant my never having been born. I have chosen to honor both of our lives—where they are inextricably joined and where they diverge—by lifting up our stories to help end the trauma imposed every day on those who live without access to the full spectrum of reproductive health care. As I’m not particularly prone to regret or any of its harmful related notions, I am not, as has been suggested to me several times by anti-choice activists, paying a penance for some offshoot of “survivor’s guilt.” I simply want better for those who are in need now, better than what was given to my birth mother.

#HelloHyde is not about love or honoring the sanctity of life. It’s about reinforcing and expanding four decades of punishing the poor, the young, the undocumented, and communities of color. I will not be erased; I will not allow my birth mother’s story to be erased. We deserve better; we deserve to have our actual lives celebrated—complete with messy, inconvenient, beautiful, traumatic, inspiring narratives. And so, to honor her, I’m going to start a new tradition of donating to an abortion fund on my birthday, with a credit to Secular Pro-Life for inspiring my annual gift.