In ‘Highway of Tears,’ a Missed Chance to Hold White Journalists Accountable

The real epidemic is the criminal way in which the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women has been historically overlooked.

“No one knows who the first Indigenous girl or woman to vanish along the highway between Prince Rupert and Prince George was or when it happened,” writes Jessica McDiarmid in her new book, drawing much-needed attention to the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women.

According to the New York Times, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) reports that 18 women disappeared or were found murdered along Highway 16 in British Columbia between 1969 and 2006. The 450-mile road runs through several remote Native communities. Community activists and members maintain the number of missing women is closer to 50.

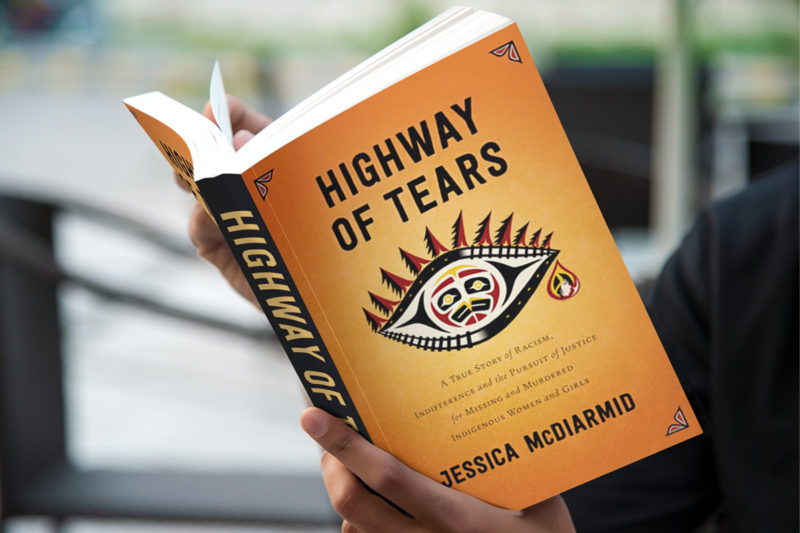

In Highway of Tears: A True Story of Racism, Indifference and the Pursuit of Justice for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, McDiarmid describes the lives of several of these women.

Unlike many other white journalists writing for mainstream outlets, McDiarmid does not dwell on the stories’ gory details. Nor does she resort to describing Native women’s lives through a reductionist lens. Rather, she gives victims and their families the sort of attention typically reserved for middle-class white victims.

Although most of the women and girls were poor, and some were involved in risky behavior such as drinking or using drugs, McDiarmid’s writing helps depict them as complex humans, loved and missed by family. She fails, however, to truly account for the failure among mainstream journalists to recognize missing and murdered Indigenous women as an ongoing crisis.

The fact is that it has been open season on Indigenous women in the United States and Canada for more than 200 years. I am an Indigenous woman: a citizen of the Ojibwe tribe of Wisconsin. Like my mother and grandmother, and likely generations of my women ancestors, I’ve been sexually assaulted, usually by white men. The men attacked us knowing that they were unlikely to face consequences for their crimes. Even if we dared to report them to law enforcement, their actions would be dismissed as youthful exuberance: minor faults of solid, contributing members of the white community. As Native women, we hardly figured as human in the men’s worldview. We were spoils for the victors.

According to the only RCMP report ever produced, there were around 1,200 missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada between 1980 and 2012; according to the Native Women’s Association of Canada, however, the number could be as high as 4,000.

As researchers including Sarah Deer, professor of women, gender, and sexuality studies at the University of Kansas, explained to me for a 2010 article at The Progressive, “Indian women have been viewed as legitimate and deserving targets for sexual violence since the earliest days of colonization. Raping Indian women has essentially been a right of conquest.”

So I can’t entirely hide my exasperation over the complacent manner in which white journalists like McDiarmid announce their discovery of the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women as though it is a recent epidemic. The real epidemic is the criminal way in which this crisis has been historically overlooked. If mainstream white journalists cover sexual violence against or murders of Indigenous women at all, they frequently include descriptions of victims’ risky behavior as somehow inviting violence—when those actions, such as sex work or hitchhiking, are often the only means for survival for the poor. Mainstream journalists seem to reserve their shock and horror over violence for the so-called true innocents: victims like themselves from white, middle-class families.

Were it not for Native families and activists’ relentless crusade via social media, mainstream journalists would likely still be covering this issue as they always have: relying on institution-to-institution communication and dismissing community concerns as unsubstantiated rumors.

Although McDiarmid gives some attention to this disparity in media coverage, she fails to truly hold her colleagues’ feet to the fire. She should interrogate the institutional racism typified by the white male perspective that defines what is considered “legitimate” news among mainstream journalism outlets.

In her extensive description of Indigenous families’ and activists’ struggle to gain the ears and attention of government, police, and press, McDiarmid devotes too much space to white fragility in a seeming attempt at fairness: She allows RCMP investigators and leaders to insist that they conducted a thorough review of the cases. She lays out police officers’ historic lack of access to resources, their sincere desire to solve crimes, and the government’s support for further inquiry. McDiarmid writes of the police’s challenges in determining whether the murders and disappearances are connected to one person. Like many middle-class white people, she cannot seem to bring herself to believe that violence against Indigenous women isn’t necessarily connected to a monstrous random serial killer. She fails to interrogate the deep, colonialist underpinnings of settler entitlement that has created an environment in which Indigenous women are legitimate targets of sexual violence.

McDiarmid does a laudable job of calling attention to the systemic causes of these crimes, such as Canada’s colonial history of theft and exploitation of Indigenous lands with little thought to the welfare of the people there. She describes the shortcomings of Project E-Pana—an RCMP investigative effort that ultimately spent a lot of money but produced few results—and the beleaguered National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, which failed to focus on inadequate police procedures.

Unfortunately, she gives only brief mention to the continued dearth of public transportation along the Highway of Tears. It is this sort of basic infrastructure failure that has been found to contribute to the issue. Women and girls are still forced to hitchhike to activities and medical appointments. According to the CBC, lack of transportation continues to be a “gaping wound” in northern British Columbia.

I began writing about the historic sexual violence toward Indigenous women in 2010; in 2016, I published a series about missing and murdered Indigenous women in the United States for Rewire.News. Since then, not a month passes without a white journalist contacting me in search of sources for their own stories on this topic.

On the positive side, McDiarmid’s book represents the beginnings of settler awakenings to the contemporary human cost of historic policies—at least, I hope so. But I remain disturbed, overall, by my colleagues’ unexamined enthusiasm in using Indigenous peoples’ reliable despair as a career opportunity to be mined for personal gain. This is an issue of life and death: one that demands bold, giant steps away from the salacious details of poverty and violence.