Federal Government Uses ‘Crack House’ Statute in Attack on Overdose Prevention Sites

Advocates said by taking legal action against harm reduction facilities, the federal government is saying "the law is the law and if more people die, tough shit."

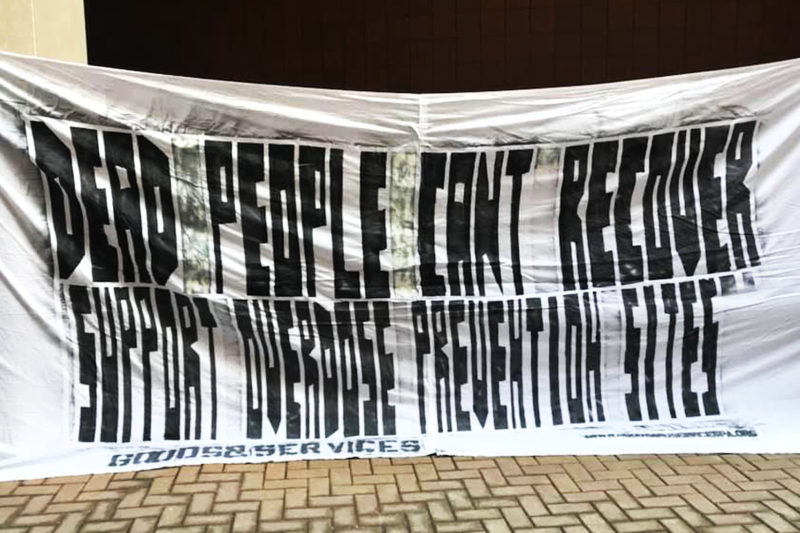

Advocates for a more humane approach to treating people with substance use disorders say they’re ready for the upcoming legal fight against the Trump administration’s attack on overdose prevention sites.

The U.S. Department of Justice took aim last week at the movement to open a supervised consumption site in Philadelphia. U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania William M. McSwain on February 6 announced his office had filed a civil lawsuit—the first of its kind—against Philadelphia-based nonprofit Safehouse, asking the the U.S. District Court to rule that safe injection sites violate federal law. SOL Collective and the Philadelphia Drug Users’ Union helped organize a group of community advocates to protest outside the U.S. Attorney’s Office that afternoon.

Ronda B. Goldfein, vice president of Safehouse, the legal entity that plans to open a safe injection site, said the federal government is using the “crack house” statute in the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. Goldfein said this law was intended to prevent businesses from profiting off drug consumption, and that Safehouse is intended to prevent further overdoses from being added to the opioid crisis’s vast death toll.

Supervised consumption sites—also known as supervised injection facilities, safe injection sites, and overdose prevention sites—provide a safe environment to consume drugs that are not prescribed by a doctor, including heroin and fentanyl, under professional medical care. At these facilities, people with substance use disorders have access to treatment referral services, counseling, and other community resources. Rooted in principles of harm reduction, these facilities are designed to fight social isolation many people who use drugs experience due to stigmatization by bringing them back into a supportive community.

“Our purpose is to save lives,” Goldfein said. “Our purpose [is] to have eyes on and reverse that overdose before it becomes fatal. Our purpose is also to get people into treatment.”

Organizers in the city’s harm reduction movement are also involved in Prevention Point, a nonprofit providing services like drug treatment, HIV testing, overdose reversal trainings, and needle exchange program to the surrounding North Philadelphia community. ACT UP Philly, a local direct action group formed in reaction to the HIV and AIDS crisis, was instrumental in forming Prevention Point, said Jose de Marco, a community organizer with ACT UP.

“By my volunteering there a great deal [and] working there, I’ve gotten to know a lot of the people that use the services at Prevention Point, and I’ve seen a lot of the people, that I personally know, have died from overdose, and they didn’t have to if they had a safe place to inject,” de Marco said. “You build relationships with people, you get really close to them, and then you come in the next day and someone says to you, ‘XYZ person died last night two blocks away.’”

The complaint against Safehouse cites the Controlled Substances Act, a federal law signed by President Richard Nixon in 1970 that led to the formation of the Drug Enforcement Administration. The law classifies heroin as a schedule I drug, alongside cannabis even when used for medicinal purposes. The law considers schedule I drugs to have a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use.

“[McSwain is] talking about law, and we’re talking about saving human lives,” de Marco told Rewire.News. “To me, [that] translated to you know, the law is the law and if more people die, tough shit.”

This isn’t the first time the federal government has threatened the proposed safe injection site in Philadelphia. In an October 2018 interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer and Daily News, McSwain said he was planning to stop Safehouse, dismissing supervised consumption sites as “fundamentally illegal.”

U.S. Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein during an interview with NPR member station WHYY in August 2018 claimed supervised consumption sites normalize drug use, arguing that people struggling with substance abuse need treatment and dismissing how effective these facilities can be in preventing overdoses.

In a recent policy paper, experts in public health law from Georgetown University Law Center and Arizona State University wrote that such facilities can substantially decrease overdose-related deaths.

The paper cites facilities in Australia, Spain, and British Columbia that have successfully curbed and prevented opioid-related deaths since opening their doors. Notably, a facility in Sydney reported no overdose deaths out of 5,925 overdoses from 965,000 supervised injections between 2001 and 2015.

Data from Sydney, Barcelona, and Vancouver have debunked the myths that rates of drug trafficking, assault, and robbery would increase in neighborhoods with a supervised consumption site. But the paper’s authors noted that to assess how effective these facilities are in the United States, they need to be tested. There aren’t any facilities in the United States from which to assess data, which makes the fight for Safehouse in Philadelphia critical for harm reduction advocates.

Other cities fighting for supervised consumption sites also face opposition from government officials. In California, for example, former Gov. Jerry Brown (D) vetoed a state bill that would have allowed for a supervised consumption site last fall, despite recommendations from drug policy experts, reports Mother Jones.

“We are continuing discussions with neighbors about where an appropriate site would be,” Goldfein said. “We are continuing to talk to folks about financial support. While we are respectful, we are going to maintain our disagreement [with the U.S. District Attorney] and move forward, even though we’ve gotten a clear indication that’s not what they want us to do.”