Racism Kills: What Community-Level Interventions Can Do About It

One such program is a school-based model in Portland, Oregon, called 3 to PhD.

For more anti-racism resources, check out our guide, Racial Justice Is Reproductive Justice.

This is the third part of a Rewire.News series on potential interventions for the health impacts of racism. Read part one here and part two here.

In the first two installments of this series, we addressed promising approaches for buffering the impact of racism on health—learning cognitive and emotional strategies, known as self-regulation, for coping with stress and building cultural connections that buffer the impacts of toxic stress. Both of those arenas are born out of social science research showing a connection between these elements and improved health outcomes, even in the face of significant adversity.

But these individual approaches beg a larger question: If we address the broader, community-level conditions that shape individual well-being, could we improve people’s health? The answer is probably, according to existing research focused on the impact of community support and systems on the health of people who have experienced adversity, as well as interventions designed to do so. While these broader interventions are more complex to implement, the benefit is that they may prevent some adversity before it ever occurs.

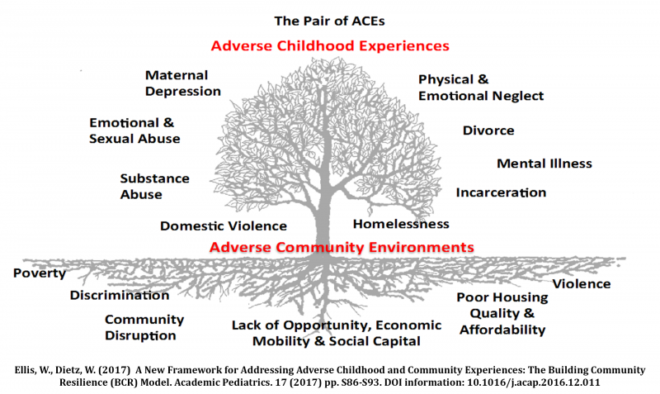

Wendy Ellis works at the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University and is the co-principal investigator and project director of the Building Community Resilience Collaborative. She and her team have developed a model to explain the connection between individual adversity and their community. In their model, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are influenced by, and maybe even born from, adverse community environments.

As we explained in part one, ACEs are childhood experiences—like abuse, divorce, or poverty—that result in extended periods of extreme stress. Adverse childhood environments, on the other hand, can include everything from a family unit to a neighborhood to the broader economy that shapes an individual’s life. “It’s not about what the individual can do in the midst of the tangled machine. We need to fix the machine,” said Ellis in a phone interview with Rewire.News.

“Yes, it’s important to treat individuals as these adversities pile up, but we need to fix the machine. Let’s be very thoughtful in thinking about the systemic inequities and access to those buffers and supports. So that we’re not just treating trauma but preventing it.”

One of the ways to quantify the support systems around an individual is to look at their level of social support. While in the last piece of this series we looked further into how cultural connection can improve resiliency in the face of racism, social support is different in that it can be broader, and is not necessarily rooted in a culturally relevant community or practice. Social support can be as simple as whether you have friends you can turn to when you’re dealing with difficult situations or emotions.

Research suggests that social support is a key factor in determining whether a person who has faced adversity will go on to have health problems. “The kinds of resources that seem to be most protective of the negative effects [of discrimination] have to do with the quality of social relationships,” said David Williams, PhD, a sociologist at Harvard University and a central figure in documenting the connection between racism and poor health.

Nicole Racine, PhD, a clinical psychologist at the University of Calgary, is leading a team of researchers that found that among pregnant women with ACEs, those with significant social support have better health outcomes than their peers without social support.

As with the other interventions we’ve covered in this series, researchers think social support has such an impact because of how it can reduce stress. “[W]hen you have less stress, you’re less likely to be sick,” said Racine in a phone interview with Rewire.News. “You also perceive your ability to cope with stressors better because you feel like you have these added resources. ‘I have these people here who will help and support me.’”

While Racine’s study aligns with Williams’ understanding of how social support influences resiliency in the face of adversity, it’s important to note that she surveyed women in Calgary, with a population that is 82 percent white, with the other 18 percent spread widely across other racial and ethnic groups. Because so few of the women she surveyed were racially and ethnically diverse, we can’t draw clear conclusions based on race within this particular study.

Another question underlying this research is whether systemic interventions that increase social support would have the same results. The existing research “really looks at naturally occurring support,” Williams said. “I think it’s actually a different question of whether we can manipulate the degree of support.”

For example, a study might take a group of people who reported experiencing ACEs and low social support, divide the group into two, and enroll half in a program focused on increasing social support, such as peer counseling or a program designed to develop supportive friendships between participants. Then researchers could compare the two groups to see if the outcomes were different, which would allow for conclusions about the role of this kind of social support.

It’s important to parse out this distinction because the findings could shape what kind of larger systemic interventions public health professionals might take on to address this problem beyond the individual level.

Ellis feels strongly about taking a systemic approach to reducing the impact of adversity, which is partially born from her own personal experiences as a Black woman. “I have an extremely high ACE score,” Ellis said. “I know a lot about resilience from the multiple supports at the family level and community level. [I had] access to quality public schools, affordable after-school activities, a strong faith community. My family also had a lot of family as well as community supports. All of those things we know can contribute and offset that exposure. All of these things were in place.”

Ellis, after starting out in journalism, decided to shift to public health because she wanted to have a greater impact on the well-being of children. Ellis and her team at the Building Community Resilience Collaborative have developed a model they call the “Pair of ACEs” to illustrate how the environment also contributes to adversity for individuals. They work with programs around the country that try to “fix the machine” by connecting “community organizations (through a church health ministry or trusted food pantry, for example) with larger systems (including those in health care, education, business, law enforcement) [to] begin to build a durable network to improve community well-being.”

One such program is a school-based model in Portland, Oregon, called 3 to PhD. That program centers the Faubion School, which Ellis said was “one of the area’s underperforming schools and in an area that had one of the highest concentrations of poverty. Ninety percent of the children were eligible for free and reduced lunch.”

While Portland has a reputation of being very white, Ellis explained that this school has a “large portion of Latino and African American students.” The pre-K through eighth-grade school built a partnership with nearby Concordia University and introduced a number of new services and programs for their students.

First, the university began “co-locating some of their college courses, and doing their practicums through the Faubion School,” Ellis said. They also added a wellness center as well as a pantry inside the school where parents can use SNAP benefits or pay by cash or credit card. “They are providing access to nutrient-dense food not available in the neighborhood,” Ellis said. The approach to teaching also has shifted to a “trauma-informed” model. A YouTube video about the program put out by Ellis’ team explains: “Instead of asking what is wrong with you, we seek to understand what has happened to you.”

“The school itself can’t change everything that is happening around [the students],” Ellis said. “But they can provide a healthy environment.”

The program sees the school as a “wellness hub,” and that hub is already showing positive results seven years into the program. “They have reduced absenteeism, they have reduced their out-of-school suspension rate,” said Ellis. “There has been a marked increase in their reading levels as well as their teacher retention.”

While the researchers don’t yet have data on health outcomes for the student population, Ellis says they are planning to track those in light of a new health center on campus by their partner Kaiser Permanente.

“Our system is designed for the outcomes we see,” Ellis said. “You have to have the will to do the system redesign.”

Because of her approach, Ellis’ work often includes conducting research beyond the traditional public health arenas. In Washington, D.C., her organization worked with Unity Health Care, a Medicaid provider but also the primary health provider within D.C. jails. “We were doing a series of focus groups with them to answer the question of what can we do to improve the health outcomes of individuals in our care?”

Ellis says the answers were not what they expected. Instead, ”the number one adversity, the number one stressor, and the biggest barrier to being healthy was interactions with Metropolitan Police Department (MPD). It’s the anticipation of the negative interactions.” So they launched a project to “facilitate dialogue between MPD and residents. To increase understanding and hopefully get to the point where there is some sort of improved relations—at least reducing stressors. We’re really trying to influence how we address some of the community-embedded adversity.”

This work with the MPD fits into the larger framework of trying to prevent adversity before it even begins. “What can we do to transform our work environments, school environments, where we stop discrimination before it occurs?” asked Williams. “Where we create a culture and a context where certain types of behavior and treatment is unacceptable and doesn’t occur?” This includes work to reduce racial prejudice and implicit bias among those with privilege and those in positions of power.

“There is some evidence of interventions that can be done with the general public that can reduce explicit racial prejudice and implicit bias,” Williams said. “There is promise that that can be done. The challenge we face is how to scale these up and deeply embed them into our cultural transmission systems. So that we can literally transform the culture of our society.”

Systems-wide change is not a small undertaking. Some might argue that the only way to truly eliminate racial bias in policing, for example, would be to eliminate the police altogether. That kind of shift requires a clear vision for the system we would put in its place that, for example, addresses and prevents harm between individuals. The reality is that it is unlikely any single intervention will work at a national level because the needs of each community are unique. The good news is that there are many people testing different approaches, offering an important entry point into this kind of change.

Among those working on this systems-level change, there was one commonality—a strong sense of optimism. Both Williams and Ellis share that approach. “I tend to see the glass as half full,” Williams said. “Even if you think of the work on discrimination. There was a time when I knew everyone doing research on discrimination and health. I don’t now. We now have evidence of interventions that we can do to reduce the negative effects. We have made enormous progress in addressing and understanding the phenomenon.”

Ellis has a similar view: constantly looking for opportunities even within what she described as a “very turbulent time.” “It took us 242 years to see the outcomes that we’re seeing today,” she said. “We’re not going to see things turn around on the dime. I don’t expect this to change in my lifetime. But when we look back on this, we’ll look back at it as a pivotal point in systems design.”

Similarly, Williams is not deterred by the amount of time it’s taking to see real progress. “Martin Luther King best sums up my view toward life: Justice is inevitable at some point even if it sometimes takes us a long time to realize the goal.”