With Gang Allegations, Educators Are Funneling Migrant Teens Into a School-to-Deportation Pipeline

“Children deserve to be able to go to school in a safe environment, without having to worry that a basketball jersey could mean deportation.”

![[Photo: Three students sit in a classroom]](https://rewirenewsgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/shutterstock_583892368-800x533.jpg)

This is the second article in a two-part series at Rewire.News on the school-to-deportation pipeline. Read the first piece in the series here.

One year after a 17-year-old asylum seeker fled El Salvador to escape gang violence, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) arrested the teen at his home on Long Island as part of a raid purportedly targeting MS-13 gang members. Known as LVM in court documents, the teen had no criminal record, no known gang affiliations or involvement, no history of disciplinary issues, and had never been arrested, or charged for a crime. He had, however, been suspended from school for flipping off a classmate, who he said reciprocated the gesture.

A faculty member who witnessed the motion—LVM raising both middle fingers to a fellow student—claimed that the teen had flashed a gang sign, prompting his suspension. And because the school district cooperates with law enforcement, which shares information with immigration officials, ICE arrested him in July 2017 at his home as part of Operation Matador four months after his suspension.

The 30-day enforcement operation in the New York metropolitan area netted 39 supposed MS-13 members, many of whom, like LVM, lived on Long Island. Advocates and legal experts say that these teens got on ICE’s radar because of information provided by their high schools to federal immigration agencies.

Under the Trump administration, schools are quickly becoming unsafe spaces for undocumented students. For young, Central American migrants in particular, navigating adolescence has become a minefield. Wearing fashionable clothing or flashing a peace sign in a Facebook picture can trigger an accusation of gang membership, which can in turn spiral into an event that leads to detention and deportation.

“Gang membership” and “gang association” are not defined in immigration statute, and definitions of a “gang” differ among law enforcement, state, and federal agencies. Yet school officials are funneling young Central American migrants into a school-to-immigration detention pipeline based on false accusations of gang membership, subjecting already vulnerable kids like LVM to even more trauma. As school officials are watching these students suspiciously, local law enforcement is monitoring their use of social media. Emboldened under the Trump administration, ICE agents are then quick to arrest and deport these young people. This culminates in, as an Immigrant Resource Legal Center (IRLC) report put it, families “being torn apart by deportation” and immigrant youth “seeing their futures destroyed at the hands of an often-false allegation or past mistake.”

While there are multiple court cases taking the Trump administration to task for violating the due process rights of immigrant minors accused of gang involvement, it seems little has been done to hold schools accountable for the ways in which they are funneling students into the detention system. And, since U.S. citizens are not unaffected by these educators’ decisions to turn school children in to the police, “this country’s stated commitment to fairness, due process, and equality is being called into question.”

“Progressive Discipline”

On paper, the South Country Central School District appears invested in student success and mindful of the costs of imposing harsh punishments on young people. A manual featuring the district’s code of conduct and approach to discipline and intervention outlines its use of the “progressive discipline” model in which discipline is considered a “teachable moment” and young people who have engaged in “unacceptable behavior” can, in part, “be given the opportunity to learn pro-social strategies and skills to use in the future.” The district also asserts that it is “committed to providing a safe and orderly school environment where students may receive and district personnel may deliver quality educational services without disruption or interference.” These strategies, however, weren’t offered to LVM during his time at one of the district’s schools, Bellport High School, nor was he able to continue his education “without interference.”

District staff consider a range of factors when responding to inappropriate conduct, including a student’s disciplinary record and the nature, severity, and scope of the behavior. “Infraction levels” range from “uncooperative and noncompliant behavior” to “seriously dangerous or violent behavior,” according to the school district’s rules. For young students—like LVM—in grades 6 through 12, “using profane, obscene, vulgar, or lewd gestures or behaviors” is only a level 2 infraction and should have resulted in a student/teacher conference, a parent conference, detention, or another mild disciplinary action. Instead, after an April 2017 hearing regarding LVM’s behavior, in which he and his mother were not provided counsel or translation services, school officials suspended the teen for 39 days.

The school district does clarify that its “progressive discipline” and “standards of intervention” are procedural guidelines that do not limit the administration from taking additional steps. But it’s a decidedly extreme disciplinary approach to contact the police and funnel a young person into the immigrant detention system for what the school’s own guidelines deem a minor infraction.

The specifics of how LVM got on ICE’s radar are murky because the school district has refused to respond to state Freedom of Information Law requests from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and has refused multiple interview requests from Rewire.News. What the attorneys in the case presume is that ICE was acting on information provided to it from the Suffolk County Police Department, which has also refused Rewire.News requests for an interview. Officials finally gave the information shared between the two agencies to LVM and his mother through LVM’s attorney at a custody hearing in December 2017, after the Office of Refugee Resettlement had already had the teen in custody for several months.

As Julie Mao, an attorney with the National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers Guild, told the Intercept in February, “It just becomes a cascading cause and effect, where you have perhaps a school administrator accusing someone of being ‘gang’ based on very thin evidence, and that becomes something that is written and put into that student’s file. Maybe there’s a suspension or some kind of school-related proceeding where there’s a paper trail—that often gets passed to the local police agency if local police is in that school, and then that gets passed on to immigration.”

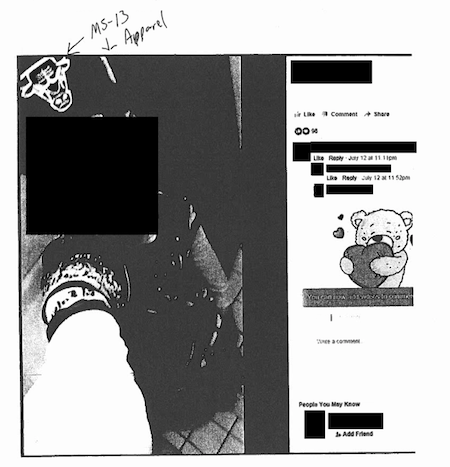

In Department of Homeland Security (DHS) referral notes from when LVM was first detained, the agency identified the teen as a MS-13 gang member and this identification was based on the classification given to him by the Suffolk County Police Department. The notes also referenced his suspension for “flashing gang signs” and his “use of apparel and clothing associated with MS-13.” The apparel and clothing are not described and, according to Paige Austin—an attorney with the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) and the lead attorney on a class action lawsuit against ORR in which LVM is a representative plaintiff—to this day, LVM and his mother still have “no idea” what clothing is being referenced. The notes also assert that LVM admitted to gang affiliation and has gang tattoos, both of which he denies.

Some of the circumstances related to LVM’s case are eerily similar to those of Daniel Ramirez Medina, a Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipient arrested at his home by ICE agents. Agents that day had an arrest warrant for Ramirez Medina’s father, but asked Ramirez Medina if he was “legally here.” When he explained to agents he had DACA, they should have released him. Instead, they detained him. ICE alleged that while still in his home, Ramirez Medina admitted that he “used to hang out with” and “still hangs out with” members of two gangs, an allegation the then-23-year-old said was a lie. According to Ramirez Medina, the questioning about gang affiliation didn’t come until he was already in ICE custody. The only corroborating evidence ICE has ever offered for its assertion he is in a gang, besides the supposed confession, comes in the form of a tattoo on Ramirez Medina.

A federal judge recently ruled that ICE had lied and as Slate noted in coverage of Ramirez Medina’s case, “ICE routinely alleges that Latino immigrants with no indication of gang affiliation are members of a gang in order to detain and deport them.”

LVM doesn’t have any tattoos, nor did he ever admit to gang membership, according to court documents. DHS also alleged that LVM appeared in a video flashing gang signs, but court documents indicate that such allegations by DHS were copied and pasted from “allegations made against other immigrant children alleged to be gang members.”

Prolonged Detention of Immigrant Teens

Because of LVM’s supposed affiliation to MS-13, ORR held him at a secure facility in Virginia from July 7 to August 18. As Rewire.News reported, these “juvenile delinquency facilities” are effectively “prisons that lock up kids,” as Austin put it.

When young people in ORR custody are detained in a “staff-secure” setting, which is the second highest security level in ORR, they are eventually “stepped down” to shelter care. This transition is an essential precursor to release, but under the Trump administration, this process now takes months, especially for children like LVM alleged to have gang involvement. This is true even when shelter staff or immigration judges have rejected the gang allegations against a child.

“In New York, we see this a lot. Kids are forced to remain in secure facilities because of allegations they are gang members, but the allegations are usually unfounded and the kids had no criminal record. The accusation has come directly from their school and it’s been filtered out to law enforcement and then ICE,” Austin said. “The facilities, to their credit, have been pushing back and trying to get the kids transferred out of secure detention environments, saying there’s no reason for them to be there.”

Indeed, staff at LVM’s facility described his behavior as “excellent,” according to court documents, and a dangerousness assessment conducted on August 8 ended with the recommendation that LVM be “stepped down to shelter care,” a less strict setting that did not require the teen have constant supervision. This effectively meant that the secure facility’s staff did not think the teen posed a danger to himself or others.

Once transferred to a staff-secure facility called Children’s Village in Dobbs Ferry, New York, the staff there had trouble getting LVM relegated to the lowest level of security available at the facility, despite reports of his “exemplary” behavior, according to court documents. Because LVM was detained as part of Operation Matador, Children’s Village staff could not initially get the teen the clearance needed.

It wasn’t until November 22, 2017—after four months in ORR custody—that LVM entered the lowest level of security at Children’s Village.

Teens like LVM accused of gang involvement are being subjected to prolonged detention without due process, according to immigration lawyers and advocates. A policy implemented by ORR director Scott Lloyd requires Lloyd’s personal approval before a young person detained in a secure facility can be released to a sponsor. This policy has devastating mental health consequences. The seven months that LVM spent in ORR custody were grueling for the teen and his mother. Previously, the pair were always together. While held at a secure facility in Virginia, LVM’s calls with his mother always ended in tears. The separation caused him “significant anxiety and sadness,” according to court documents.

Once the teen landed in Children’s Village in New York, his mother visited him every other week for two hours, paying a private taxi company $150 to transport her from Long Island to and from the facility. Because ORR only allowed the teen two outgoing phone calls of 20 minutes each week, his mother attempted to call him every day for the allowed ten-minute conversation, according to court documents. LVM often could not connect with his mother over the phone because there was one line being used for the almost 20 young people in the teen’s unit, many of whom were equally desperate to speak to their loved ones.

LVM’s many months in detention complicated the mental health issues he experienced. Compounding the communication issue, the teen reportedly experienced “bullying and social isolation” while in ORR custody, according to court documents.

In FY 2017, the average length of stay for a child in ORR custody was 41 days, but this number is only inclusive of shelters and transitional foster care, according to the agency. LVM spent more time than that in a secure facility alone.

Lloyd’s policy subjecting immigrant children to prolonged detention is the subject of the class action lawsuit filed by NYCLU in February 2017. The lawsuit shows that there are children who were subjected to prolonged detention well before the Trump administration’s appointment of Lloyd. JMRM, for example, had been detained for four years by the time he was 15. (Unlike LVM’s case, JMRM had not been tied to a gang.) Under Lloyd, however, ORR stalled his release because he had spent time in a staff-secure facility due to behavioral issues stemming from mental health issues and past trauma. Shortly after NYCLU filed its lawsuit, ORR released him.

Earlier this month, NYCLU filed a motion asking a judge to halt ORR’s new policy to ensure immigrant teens in custody in New York are “promptly released and reunited with family members,” according to a statement from the organization. Even as the class action lawsuit plays out in courts, Lloyd’s policy is still in place.

“Honestly, a lot of people weren’t aware that a formal policy had been put in place and that’s because ORR never made any statement explaining its policy or why it had imposed the requirement of Lloyd’s approval for releases,” Austin said. “It was through caseworkers repeatedly saying no to attorneys or family members that it became clear it had all of a sudden become really difficult to get kids out of ORR custody.”

NYCLU is currently waiting for a judge to set a hearing regarding its motion, but in the meantime, Austin told Rewire.News she wants people to understand that years before the Trump administration, there were individual reports of children being subjected to prolonged detention. Under Trump, it’s now policy.

“There has been a qualitative change in terms of how many children have been subjected to prolonged detention and now prolonged detention has been systematically incorporated into ORR policy,” Austin said. “Given that only 12 percent of kids impacted by this are being reunited with their families means they are simply being detained indefinitely, aging out and being transferred to ICE, or really just giving up and leaving the United States because they can’t stand to be detained any longer. It’s hard not to see these outcomes as intentional on behalf of ORR, but what has been intentional is the policy change. It’s also unlawful.”

Gang Allegations Have Far-Reaching Consequences

For more than a year, NYCLU has suspected “cooperation between the Suffolk County Police Department, the South Country Central School District, and federal immigration authorities,” which has “led to dozens of children being removed from their families, placed in restrictive detention facilities, and into deportation proceedings based on spurious claims of gang affiliation.”

Around the time that LVM was first detained by ICE in the summer of 2017, NYCLU noted on its website that it began to receive information from families that ICE was targeting their children for removal “based on flimsy evidence and vague criteria” related to gang involvement. But there were other commonalities among some of the young people being targeted: They attended school in the South Country Central School District and before their detainments, they were suspended because of supposed gang affiliation.

LVM isn’t the only student that ICE targeted after Bellport High School suspended him. NYCLU announced in April that ICE targeted two other students because of so-called gang affiliations first alleged by the school.

Perhaps because there have been incidents of gang-related violence on Long Island and President Trump has made repeated visits to the area to conflate young Central American asylum seekers with violent MS-13 members, including one such trip that took place this week, the South Country Central School District has been on high alert regarding gang membership. Advocates say this may be why teachers and administrators are so quick to inform local law enforcement of perceived gang activity.

NYCLU notes that school officials suspended one student for displaying a Salvadoran flag on his personal Facebook page, which they saw as evidence of gang ties. More commonly, the school has used its vague dress code policy to target immigrant students. The policy prohibits clothing determined by police to be gang-related, but neither the police department nor the school specifies what exactly is prohibited. Entire cases alleging gang activity have been built based on one item of clothing. For example, officials suspended one Bellport High school student for wearing a shirt with a small Chicago Bulls logo on it, according to NYCLU.

In the school district’s code of conduct, the sole dress code reference warns students against “wearing clothing, headgear, or other items that are unsafe or disruptive to the educational process.” The only other information on the school website related to dress code protocol instructs students to remove their hats, hoods, bandanas, and doo rags upon entering the school building.

A great deal of space on the school’s website is dedicated to resources for helping parents identify if their children are in gangs. There are guidebooks from the Department of Justice’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) and pamphlets from the Suffolk County Department of Probation, both of which ascribe gang affiliation to behaviors, clothing, and interests that typify adolescence.

For example, the OJJDP cites everything from beaded necklaces and colorful fabric belts to “gangster rap” and “withdrawing from family activities and planned events” as “common gang identifiers” for parents. In a manual called “How To Talk To Kids About Gangs,” written by Bellport High School social worker, Lynette Murphy, the “What Can We Do?” section recommends working with the police, reporting “suspicious activity,” and sharing information, but there is no mention of racial profiling or the conflation of immigration with criminality. Murphy could not receive approval from the district to speak to Rewire.News about any training teachers or administrators receive to identify potential gang members.

A statement to Rewire.News on behalf of Dr. Joseph Giani, the superintendent of the South Country Central School District, said the superintendent would not address LVM’s specific case because “the disclosure of student identifiable information under the circumstances is prohibited by federal law,” but it did say the board of education “is committed to providing an educational environment that promotes respect, dignity and equality.” The statement also contended that it is not the role of the school district to “determine if someone is in a gang,” and that the district contacts the “appropriate local law enforcement agencies for those violations that constitute a crime and/or substantially affect the order of security of a school.”

When asked to clarify if there is a policy in place, or if it is up to the individual discretion of teachers and administrators to choose to contact law enforcement when students make lewd gestures or post a picture of a different country’s flag on Facebook, for example, the district did not respond.

ILRC’s recent survey revealed just how severely schools like Bellport are harming undocumented students by making unfounded allegations of gang affiliation. Deportation By Any Means Necessary: How Immigration Officials are Labeling Immigrant Youth as Gang Members details findings from a national survey of immigration attorneys who have represented young people accused of gang affiliation in immigration proceedings, revealing that 50 percent of immigration attorneys surveyed have seen an increase in allegations of gang involvement against their young, undocumented clients. In more in-depth interviews with a smaller number of lawyers, 73 percent reported they have specifically noticed this increase over the last two years.

Gang allegations can affect immigration status in a variety of ways, according to the report:

In addition to gang-related convictions making immigrants ineligible for various forms of relief from deportation, gang allegations may also increase chances of immigrants being detained during the pendency of their immigration cases, which has devastating consequences for the likelihood of fighting deportation. Additionally, most pathways to lawful permanent residence are discretionary, so a mere allegation can be sufficient for an adjudicator to negatively exercise their discretion. In practice, even the “mere perception of criminality” can impact immigration status because so many decisions turn on credibility determinations.

Judges can deny bond to immigrants based on a young person being perceived as a “danger to the community.” In such cases, accusations of gang affiliation are especially harmful. For adjustment of status, asylum, and deferred action, according to the ILRC, individual judges and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) officers have a great deal of discretion in their decision-making and allegations of gang membership color these decisions.

ILRC’s survey results mirror other circumstances documented in a new report published by the New York Immigration Coalition and the Immigrant and Non-Citizen Rights Clinic at the CUNY School of Law, which also found that gang allegations have far-reaching consequences. As reporter Prachi Gupta put it, they “become the basis for visa application denials, detention without due process, and even deportation. It’s a cycle and a trap: The thing you are being accused of becomes the reason you can’t contest the accusation.”

When immigration authorities target young people because of alleged gang ties and transfer them to ORR custody, their formal education also stops. As NYCLU’s Paige Austin told Rewire.News, “ORR’s educational offerings are very different than a regular school system. All of the kids in the facility are put in one room, meaning kids who only speak Spanish or another language, along with kids who primarily speak English. These are kids of all ages, all grade levels, all abilities in one room. It’s not really an education.”

LVM and his mother asserted in court documents that while in federal immigration custody, the teen received a “lower standard of education than he would in regular school” and that the classes at the facility where he was detained were “not part of a district-accredited program.”

Although Trump and his administration defend their attacks on immigrant children as justified in its war on gangs, the impact these efforts are having on communities is widespread. For the children caught up in the gang dragnet, their lives will forever be altered. As NYCLU Executive Director Donna Lieberman explained in a statement, “No one should be subjected to suspension on a whim, especially when it can lead to immigration officials tearing you away from your home.”

“Children deserve to be able to go to school in a safe environment, without having to worry that a basketball jersey could mean deportation.”

Read part one of the series on the school-to-deportation pipeline here.