‘Ganawenjiige Onigam’: A New Symbol of Resilience in Duluth, Minnesota

The painting is the first piece of public art in Duluth for and by indigenous people, according to AICHO Arts and Cultural Program Coordinator Moira Villiard.

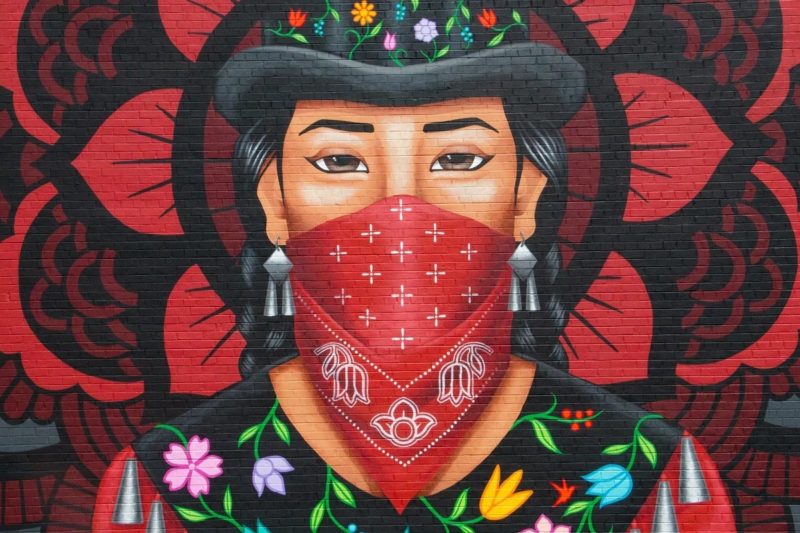

A colorful new mural in downtown Duluth, Minnesota, is a potent declaration of the issues facing Native American women such as violence, sex trafficking, and environmental racism. Primarily, however, the enormous portrait of an Ojibwe woman is a symbol of resilience, according to supporters.

Painted on an exterior wall of the American Indian Community Housing Organization (AICHO), and completed in August, the mural depicts an Ojibwe woman dressed in a red jingle dress and wearing a red bandana covering part of her face. AICHO is the only Native American shelter providing services to battered women and their children in the seven-county area surrounding Duluth. The organization also provides housing services for people suffering from long-term homelessness and transitional housing for survivors of domestic abuse.

Although vibrant and beautiful, the mural is far more than mere decoration. Titled “Ganawenjiige Onigam” (“Caring for Duluth” in the Ojibwe language), the painting is the first piece of public art in Duluth for and by indigenous people, according to AICHO Arts and Cultural Program Coordinator Moira Villiard.

A collaboration between AICHO and Honor the Earth, a nonprofit environmental conservation organization based in Callaway, Minnesota, the mural was created by Mayan artist Votan Ik with the assistance of Derek Brown of the Diné or Navajo tribe.

According to Ik, the bandana covering the woman’s face is a reference to women who participated in the Zapatista uprising in the Mexican state of Chiapas in 1994. After the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), an armed group of indigenous and poor people organized into an army named after Emiliano Zapata’s revolution of 1910. The cornerstone of Zapata’s revolution was protection of Native land and peasant holdings; the Zapatistas of 1994 feared that NAFTA would open the door to sale of their lands to private corporate interests.

“Ik told me that the bandana also refers to the Water Protectors at Standing Rock who often wore bandanas to hide their identities from police and protect themselves from tear gas,” Villiard said.

“The bandana also gives her a more universal appeal as an ‘every woman,’” Villiard noted.

The jingle dress worn by the woman in the mural has special significance to Ojibwe people. A woman dancing in her jingle dress is thought to possess great powers to heal.

There are various stories about the origins of the jingle dress.

“I was told that long ago during a time of sickness, a man dreamed of the jingle dress that would heal the people. He and his wife made the first dress,” said Sarah Agaton Howes, Anishinabe or Ojibwe from the Fond du Lac Reservation in Minnesota.

Howes, artist and entrepreneur, teaches other women how to make jingle dresses.

“Even today, making and wearing the dress helps us heal ourselves,” according to Howes.

Making a jingle dress requires hard work and commitment even for the simplest pattern. The dress holds 365 jingles, one for each day of the year. Each jingle, usually made out of snuff can lids turned into the shape of a cone, symbolizes a prayer. Each jingle must be individually secured to the dress but only after all the ribbons and appliqué are in place. The jingles make a pleasant, “shush shush” sound as the dancer moves.

Wearing the jingle dress also carries a responsibility. “We conduct ourselves with dignity and pride as Anishinabe women when we wear our jingle dress,” Howes said.

“I was told that when I dance jingle, I should keep my steps low and always keep one foot on the ground. I try to dance with intention,” she added.

Now embraced by other tribes, the dress has most recently been worn in red to symbolize and draw attention to the issue of missing and murdered indigenous women.

Red jingle dress dances are now organized throughout Indian Country to call attention to the often-overlooked issue.

Another important message in the Ganawenjiige Onigam mural is a reference to the Ojibwe people, whose traditional homelands include the city of Duluth. Indeed, the region is home to several Ojibwe reservations, including the Fond du Lac Reservation about 25 miles west of the city. The distinctive Ojibwe floral patterns decorating the hat and dress of the woman are important references to the close proximity of indigenous peoples.

“There is nothing in Duluth to let people know they are on Ojibwe land,” Villiard pointed out.

“The mural, however is an undeniable symbol declaring the presence of Ojibwe and indigenous people in general,” Villiard noted.

In the past, Duluth has been cited in the media as an unfortunate example of high rates of sex trafficking and violence against Native women.

According to now-retired Lt. Scott Drewlo of the Duluth Police Department, organized crime in the form of gangs has long-played a large role in trafficking Native girls and women in and around Duluth. For years, citizens, as in so many other cities, looked the other way, regarding prostitution or sex trafficking of Native women as an unavoidable part of the rough and tumble reputation of a port city.

Even “with her face covered, the woman in the mural is visible in a way that all those women who have disappeared or been abused have not been visible,” Howes said.

“The image may make some people in the community uncomfortable, but maybe that’s OK,” she added.

“The mural is powerful, in a spiritually and deep-down emotional way. Its interconnections with the importance of protecting our water, indigenous women, and cultural ways will now be front and center in downtown Duluth,” said Ivy Vainio of the Grand Portage Band of Ojibwe. Vainio is program coordinator at AICHO.

An official mural unveiling ceremony and silent auction are planned on Saturday, September 23, at the Dr. Robert Powless Cultural Center, an auditorium within the AICHO building at 6:00 p.m.

Proceeds of the auction will help pay for artists travel to attend the ceremony.

Speakers will include mural artists Votan Ik and Derek Brown as well as Winona LaDuke, a well-known Ojibwe environmental activist and co-founder of Honor the Earth.