‘Medicare for All’ Bill Could Be Single Greatest Advancement in Reproductive Health Care in a Century

The bill from Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) would unapologetically cover comprehensive reproductive health care (yes, including abortion) for everyone in the United States.

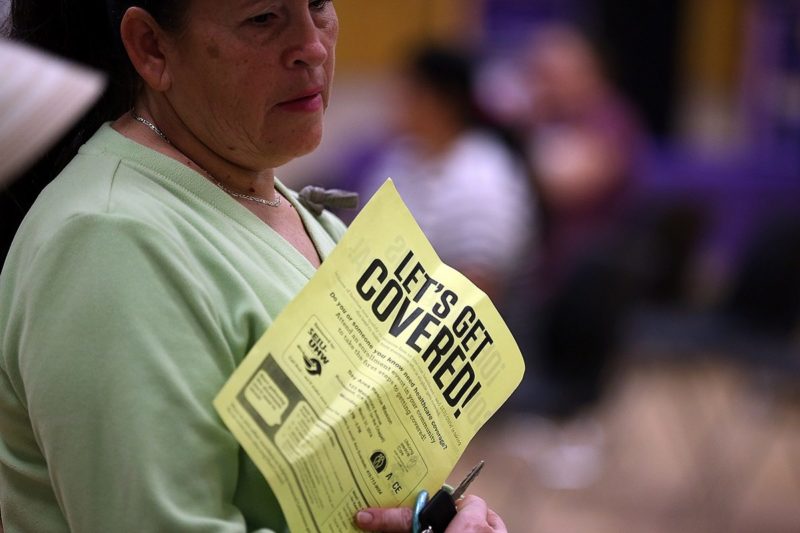

As the GOP continues to look for ways to take health insurance coverage away from millions of people in the United States, and the Trump administration does its part to sabotage Obamacare insurance markets and enrollments, Senate Democrats are quickly coalescing around a “Medicare for All Act of 2017” to be introduced Wednesday by Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT). Rewire reviewed an advanced copy of the legislation, which would establish a national health insurance program for every resident of the United States.

Once derided by many in the media and even some Democrats as a “crazy liberal pipe dream,” Sanders’ legislation is a first step toward fulfilling the fundamental human right of everyone in the United States to have access to primary preventive and curative care—irrespective of income, geography, race, gender, sexual orientation, or pre-existing condition. It establishes a Universal Medicare Trust Fund under the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), paid for by taxes and through other means and with funds to be appropriated by Congress. Each resident is “enrolled” upon birth and provided a health-care card to use when seeking care.

By unapologetically covering comprehensive reproductive health care (yes, including abortion) for everyone, the Sanders bill would also spur perhaps the greatest expansion in access to reproductive health care in this country in the last century.

In its draft form, the bill clearly sends the message to all individuals in the United States: You deserve health care. You have a right to health care.

The legislation, which currently has 15 Senate Democratic co-sponsors, galvanizes a much-delayed and oft-belittled public conversation about universal access to care that goes well beyond where the Affordable Care Act (ACA), as important as that is, can take us. The ACA, or Obamacare—originally passed in 2010 and until then also considered by many pundits and lack-of-visionaries as “a liberal pipe dream”—dramatically reduced the number of uninsured people in the United States, from just under 50 million in 2010 to roughly 28 million in 2016. Millions remain uninsured due in part to the continued reliance by the ACA on private insurance companies, but even more so as a consequence of vociferous Republican opposition to reducing the costs of premiums, expanding Medicaid for low-income populations, and including an essential benefits package. Under our current system, medical care tends to concentrate in larger urban areas, so geography also plays a large role: Some 60 million U.S. people in America live in areas without sufficient access to primary health-care providers.

Sanders’ approach seeks to eliminate these gaps. That means the hourly worker at Walmart would have the same access to basic health care as the Equifax executive pulling down $14 million per year.

Moreover, the bill is transformative in other ways. While the ACA includes many reproductive health services in its own essential benefits package, the Obama administration caved to so-called conservative and religious ideologues in carving out exceptions for the birth control benefit, which guarantees patients access to contraception without a co-pay. These exceptions were later used in court by opponents of contraception to further weaken the benefit. Further, the administration acceded to demands of far-right legislators in accepting amendments to the ACA that grossly limited access to abortion care and helped spur the elimination of private insurance coverage of abortion at the state and national level, coverage that the vast majority of women with private insurance already had. In addition, the administration used executive power through HHS to expand application of the Hyde Amendment, which bans federal funding from being used for most abortion care.

Sanders’ bill explicitly places reproductive health care where it belongs: as part of primary preventive care accessible to anyone who needs it. It also explicitly prohibits application of the Hyde Amendment to the Trust Fund set up to pay for health services. In short: abortion care is covered. And the bill was “written to cover abortion, explicitly,” said a Sanders staffer.

By proactively stating the aim of eliminating the Hyde Amendment, Sanders will hopefully force ostensibly pro-evidence Democrats to actually understand and become comfortable discussing the public health, medical, and human rights aspects of reproductive health care, including contraception and abortion care. This is an area in which, for all their “pro-choiceiness,” Democrats have historically fallen far short. The bill also ensures that the HHS secretary, charged with overseeing the fund, can’t discriminate against reproductive health-care providers.

What does universal access to reproductive health care mean for the United States? This country lags far behind other high-income countries on virtually every measurable reproductive health outcome. We have higher maternal mortality rates (especially among Black women) and higher rates of neonatal and infant deaths (especially among infants of color) than do other economically and medically advanced countries. We sustain far higher rates of unintended and unwanted pregnancies because too few sexually active people have access to and understand how to use contraception. We have higher rates of sexually transmitted infections. And we pay dearly for these outcomes both individually and as a society. Sanders’ bill is the first and only bill among those now being circulated that addresses these and other concerns without hesitation or apology.

It is perfect? No. There is no explicit mention, for example of comprehensive sexual health care, which is integrally related to but often separate from reproductive health care and is needed by a far broader population than those who may become pregnant. It does not yet effectively address the clash in this country between “religious belief” and public health, especially when it comes to women and LGBTQ people. Sanders’ staffers underscored that the bill is not a “panacea for racial inequities in health care,” but rather seeks as a starting place to address economic disparities. And it does not at this stage tackle how on the one hand to ensure that health-care decisions are made on the basis of available public health and medical evidence, and at the same time, to provide counterweights to lobbies in the medical and insurance industries who, for financial gain, might push for a specific set of treatments or drugs even when proven ineffective. There are also many other areas of debate raised by the draft bill otherwise beyond the scope of this piece.

Debate is, according to Sanders’ staffers, the point of this draft bill. Like any piece of bold legislation, it has to start somewhere by inviting discussion and critique. It is a blueprint, an outline, a point of departure. There are many issues left to be considered and a million details to be ironed out. But to create a program, you have to have a vision, and the draft of Medicare for All is far more detailed than most at this point in its evolution.

Perhaps the greatest uncertainty in achieving universal access to reproductive health care in a Medicare for All program rests with the Democratic Party and progressives writ large. Such a bill would be a test of how deeply Democrats—and Senator Sanders himself—understand and are committed to promoting evidence-based coverage of reproductive health care as critical public health and human rights imperatives and how committed they are to leading and educating the country on these issues instead of bowing to the lowest common denominators in discourse about abortion care, or if they will fail as leaders in an area of critical health care they have so often used as a bargaining chip.