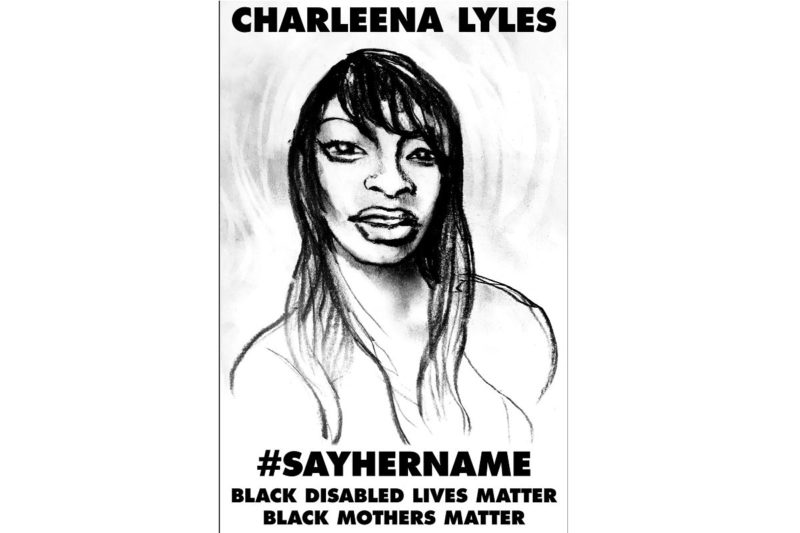

A Deadly Three Minutes: The Web of Police Violence That Killed Charleena Lyles

Bias against Black mothers, perceptions of people in mental health crisis, and policing of poverty may have all played a role in the fatal shooting of the 30-year-old pregnant Seattle woman.

For more anti-racism resources, check out our guide, Racial Justice Is Reproductive Justice.

In the midst of a weekend of nationwide protests demanding accountability for the police shooting of Philando Castile in front of his partner and her child, two Seattle police officers responded Sunday to a call for help from Charleena Lyles, a 30-year-old Black mother of four. She was reporting a burglary.

What happened next weaves together several strands of a deadly web of police violence against Black women—including police perceptions of Black mothers and Black women in mental health crisis, police responses to domestic violence, and policing of poverty.

Once the officers arrived at the apartment complex where she lived, Lyles can be heard on audio recorded by the officers’ dashboard camera. She let the officers into her apartment building and calmly and rationally answered their questions. She said that someone broke into her house while she was at the store, told the officers that she had no idea who it was, and described what was taken. The sounds of children are audible in the background.

Suddenly, the officers begin shouting, “Get back! Get back!” One officer calmly suggests using a Taser; another responds, equally calmly, that he doesn’t have one. Within seconds, a series of shots ring out.

The officers had entered the apartment at 9:37 a.m. By 9:40 a.m., they were shooting.

Although completely inaudible on the recording, the Seattle Police Department transcript of the camera footage claims that within seconds of telling officers that the intruders went through an open bag of clothes on her bed, Lyles suddenly said “get ready, motherfuckers” and was holding two knives. Given that the incident took place inside her home, where only Lyles and her children were present, away from other witnesses or cop-watching cameras, we may never know the truth of what happened in that moment.

What we do know is that the two white officers shot Lyles, who was five months pregnant, to death in front of her three children aged 11, 4, and 1, during her request for police help.

Her cousin, Wanda Cockerhern, later said, “They destroyed the four lives of her children. …. Her 11-year-old son had to walk over his mother’s dead body …. I want justice, and we want answers.”

When police violence is framed as a reproductive justice issue, the focus tends—rightfully—to be on Black mothers’ right to parent without fear that their children will be killed by police. However, equally critical to a reproductive justice analysis of policing is the reality that Black pregnant women and mothers like Lyles are also direct targets of police violence, often in front of their children.

While not always deadly, police disdain for pregnant Black women is strikingly common. At times, such violence is explicitly couched in hatred of Black motherhood. For instance, Nicola Robinson said a Chicago police officer yelled, “You Black bitch, you better be glad I didn’t hit you hard enough to make you lose your fucking baby” when he punched her in the belly while she was eight months pregnant in 2015. In another incident, an unidentified Black woman cited in a police brutality lawsuit reported that another Chicago officer said, “We don’t like Black pregnant women” and his partner slapped her.

At other times, as in Lyles’ case, officers exhibit deliberate disregard for the health and well-being of Black mothers and their children—in this egregious instance by shooting into an apartment full of children, hitting and killing a woman who was five months pregnant. In one 2012 incident, Kwamesha Sharp recounted that Harvey, Illinois, officer Richard Jones told her he didn’t care she was pregnant as he drove his knee into her belly; she later had a miscarriage and was awarded $500,000 in a settlement; the same officer was accused of raping another pregnant woman. The same year, Chicago Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy offhandedly defended officers who used a stun gun on visibly pregnant Tiffany Rent in front of her two children during an interaction over an alleged parking violation, saying “Well, first of all, you can’t always tell whether somebody is pregnant.” A Baltimore officer said, “[We] hear it all the time,” after wrapping his arm around Starr Brown’s neck, slamming her face to the ground and pushing his knee in her back as she and her neighbors repeatedly told him she was pregnant in 2009; Brown was later awarded a settlement of $125,000.

Black women have more to fear than immediate physical violence from law enforcement. Lyles’ family members also noted that she was afraid that authorities intended to take away her children. Such fears are well founded–according to legal scholars and family defense practitioners, “in practice, Black children are more likely than other children to be removed when there is no imminent safety concern, and are less likely to be offered voluntary in-home services so that they can remain at home.” Police play an often invisible role in instigating and facilitating removal of Black children from Black mothers, a reality that deeply informs Black mothers’ interactions with them.

At the core of Lyles’ killing is the question of police responses to people who are or are perceived to be in mental health crisis. As many have noted, existing research indicates that a third to half of police killings involve people with disabilities. Police responses to Black women in mental health crises are driven by long-standing perceptions of Black women as, in the words of historian Sarah Haley, “monstrous,” “deranged subjects,” to be met with force and punishment rather than compassion and care. Such perceptions also proved deadly for Deborah Danner, Shereese Francis, Kayla Moore, Eleanor Bumpurs, and countless others. Before they even walked in the door, despite the fact that Lyles was described by family members as “tiny,” weighing less than 95 pounds, both officers responsible for her death had already framed her as a threat, a factor which no doubt contributed to their decision to shoot rather than making any effort to de-escalate the situation.

The Seattle Police Department (SPD) has a history of police shootings and excessive force involving people who are or are perceived to be in mental health crisis. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) found “a pattern or practice of using unnecessary or excessive force,” noting that the “trend is pronounced in encounters with persons with mental illnesses.” The Seattle Police Department itself estimated that 70 percent of “use of force” encounters involve people with mental illness or under the influence of drugs or alcohol. The DOJ concluded that “instead of consistently attempting to de-escalate these encounters, SPD officers too often resort to force quickly and excessively when engaging with this population.” Sadly, five years after the entry of a consent decree intended to address this pattern, Lyles nevertheless fell victim to it. The DOJ also found that half of cases of excessive force involved people of color—in a city that is nearly 70 percent white.

The officers’ pre-existing perceptions of Lyles were also probably based in part in the report from a June 5 incident. Then, officers responded to a call for help, this time involving domestic violence. They claimed Lyles brandished a pair of scissors and refused to let them leave the apartment. That time, officers simply stayed at a distance, placed furniture between themselves and Lyles as she sat on the couch with her daughter, and waited for a supervisor to successfully de-escalate the situation.

Like many Black women survivors of violence, Lyles was arrested instead of receiving assistance. In her case, she was taken into custody for aggravated assault on a police officer, held in jail for ten days, and mandated to obtain mental health counseling. We can only imagine the impact that experience had on Lyles’ perception of police who responded to her call for help weeks later. But we do know that officers reading the report of that incident were prepared to treat her not as a victim, but as a suspect and a threat.

“Each time she called, it cost her something,” Cockerhern, Lyles’ cousin, said. “This time it cost her her life.”

Last but not least, Lyles lived in housing for people transitioning out of homelessness and located in the affluent, predominantly white neighborhood of North Seattle. Local organizer Senait Brown describes overwhelming police presence in the area, where there is a concentration of Black people isolated from broader Black communities. “Folks have been living in fear, of the police, of losing their housing if something goes wrong,” Brown said in a recent interview. Family members shared that Lyles too was concerned that the company that manages her apartment complex was trying to get rid of her.

Each of these factors—and all of the perceptions of Black women, people with disabilities and low-income people that contributed to Lyles’ killing— deserve the concerted attention of our movements for reproductive, racial and gender justice. Devaluation, demonization, and disregard for the health and well-being of Black mothers and their children informs violent and deadly police responses, the absence of alternatives to police responses to mental health crises and domestic violence, and the criminalization of poverty.

Hundreds joined family members for vigils outside Lyles’ home and marches in Seattle, while people took to the streets in protest in Harlem and on Chicago’s South Side. Black Lives Matter Los Angeles will host a gathering tonight in her honor. Across the country, we have expressed collective outrage over the killing of a woman described by her younger sister, Tiffany Rogers, as “a very sweet, calm person.” She added that Lyles was “full of life …. Her kids were her everything …. Anyone that came across her, she touched them in a special way.”

Family, community, and Color of Change are calling for accountability for the officers involved. Beyond immediate calls for justice for Lyles, our charge is to firmly and permanently expand our analyses of police violence and reproductive justice, along with our demands, to address the full truth of Lyles’ life and death. We must also more deeply commit to envisioning and enacting alternatives to police responses to people in mental health crisis.

Changing police policies and training are clearly not enough: On Wednesday, it was revealed that one of the officers who killed Lyles was “a certified crisis intervention specialist.” In the words of Shanelle Matthews of Black Lives Matter, “It’s time that we innovate on some 21st-century approaches to community safety and accountability.”

That’s the least we can do to to honor the memory of Charleena Lyles and prevent another Black mother’s life from being stolen.