Is God a Winning Strategy for Democrats?

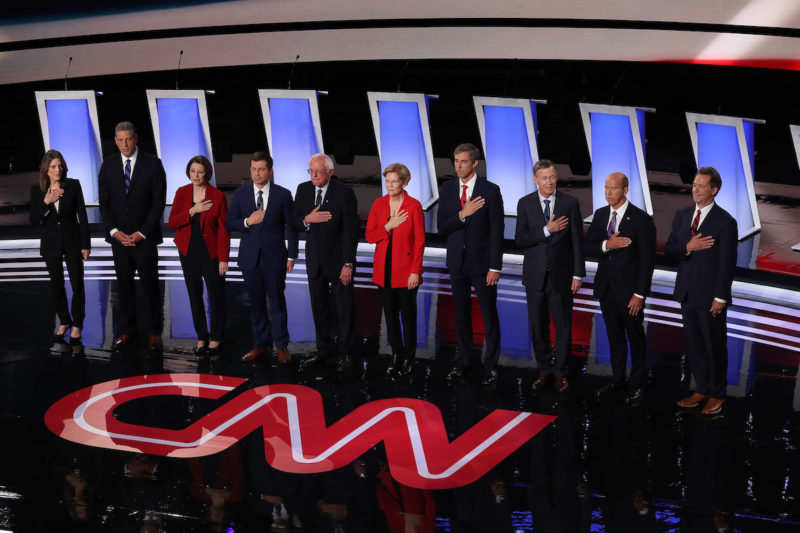

Pete Buttigieg and other Democrats have begun to talk up their Christian beliefs in hope of appealing to more voters, but there are a few problems with that approach.

Conservative Christians aren’t real Christians. That seems to be the argument Democratic hopeful Pete Buttigieg was making when he lambasted “so-called conservative Christian senators” at this week’s Democratic Debate. Then he quoted Proverbs. Mayor Pete was building on the “#FakeChristian” line of attack used against Vice President Pence after his trip to the border.

This rhetoric may seem effective because many Christian voters don’t like the Trump administration using their religion to justify putting children in cages. But the rhetoric is unsound for two reasons. First, one can easily find biblical or theological support for either side of the issue, and second, it’s less likely to sway a swing voter than it is to turn off the fastest growing voting bloc: the “Nones.”

Mayor Pete said something similar in the last debate.

The Republican party likes to cloak itself in the language of religion. Now, our party doesn’t talk about that as much, largely for a very good reason, which was: We are committed to the separation of church and state and we stand for people of any religion and people with no religion

But we should call out hypocrisy when we see it. And for a party that associates itself with Christianity, to say that it is okay to suggest that God would smile on the division of families at the hands of federal agents, that God would condone putting children in cages, has lost all claim to ever use religious language again.

I cheered. I cheered for the lines and especially for the mention of state-church separation in the debate and I wish more candidates would proudly invoke that American invention.

But Buttigieg’s argument does not necessarily flow from the Bible he quotes. Though he thinks it impossible “that God would smile on the division of families,” Jesus himself said he came to divide families: “Do not think that I came to bring peace on earth. I did not come to bring peace but a sword. For I have come to set a man against his father, a daughter against her mother … and a man’s enemies will be those of his own household.” In Luke, he explicitly says, “Do you think I came to bring peace on earth? No, I tell you, but division.”

And sure, Jesus was talking about dividing families along religious lines, but remember that the White House also justified the child separation with Romans 13. To argue against division and family separation is the morally superior position, but it is not the only biblically-sanctioned one.

That liberal Christians like Buttigieg adopt the morally superior position isn’t surprising—most Christians are better than Christianity. They employ their personal moral code, choosing the moral morsels from the Bible that square with their contemporary sensibility.

The Bible does not portray Jesus as a liberal powerhouse. Or at least, not solely as the man liberal Christians claim. We need look no further than hell to prove this point. Americans possess an unparalled degree of religious liberty, but Jesus promises eternal torture if they exercise that freedom to worship anyone but him. His musings that we should “turn the other cheek” and “love our enemies” from Matthew 5 are lovely sentiments, but they are—and should be—tempered by the everlasting torment Jesus implies in passages like Mark 16:16, in which he says “…the one who does not believe will be condemned.”

In his recent op-ed in The Atlantic, Senator Chris Coons (D-Del.) argued that Democrats should speak more openly about their religion, pointing to Senator Sherrod Brown as an example. In this retelling, Brown won re-election in 2018 because he took Coons’ advice. Never mind the pesky facts that incumbents win reelection well over 80% of the time and that Brown had won his previous two races by an average of over 9%.

Throughout history, religious, theological, and biblical arguments have been used to justify slavery, segregation, and the subjugation of women. Even Martin Luther King, Jr.—who some readers have already mentally invoked as a counter argument on reading this article—understood this at some level, though his arguments blazed the trail Buttigieg and Coons are walking. King’s Letter from the Birmingham Jail is addressed to “My Fellow Clergymen.” In that original letter and elsewhere, he criticized the church for being a taillight and not a headlight, inadvertently echoing the argument that secular activism often drags religion into progressive causes. Again, most Christians are better than Christianity.

Liberal believers might need to argue over which party a “true” Christian would support, but politicians do not need to make these arguments. Which brings us back to the 2020 election.

Coons suggested that the Democrats inject more religion into their party. Buttigieg seems to agree and is using it as a cudgel against Republicans. A better suggestion, one that both parties should employ, is the one Tara Isabella Burton made over at Religion News Service in a story about some campaigns hiring faith engagement specialists: “In coming years, Democratic candidates in particular may need to focus on hiring a ‘nones engagement’ specialist alongside a faith-based one.”

Invoking religion is unlikely to convince conservative Christians to come over to liberal Christianity. It may, however, energize conservative Christians, white evangelicals, and Christian nationalists while turning off the “nones” at a time when they are ripe for political courting.