With Black Women at High Risk for HIV, Why Are So Few Taking the Prevention Pill?

One in 48 Black women in the United States will contract HIV in her lifetime. But knowledge of—and access to—the pill that can prevent infection remains a problem.

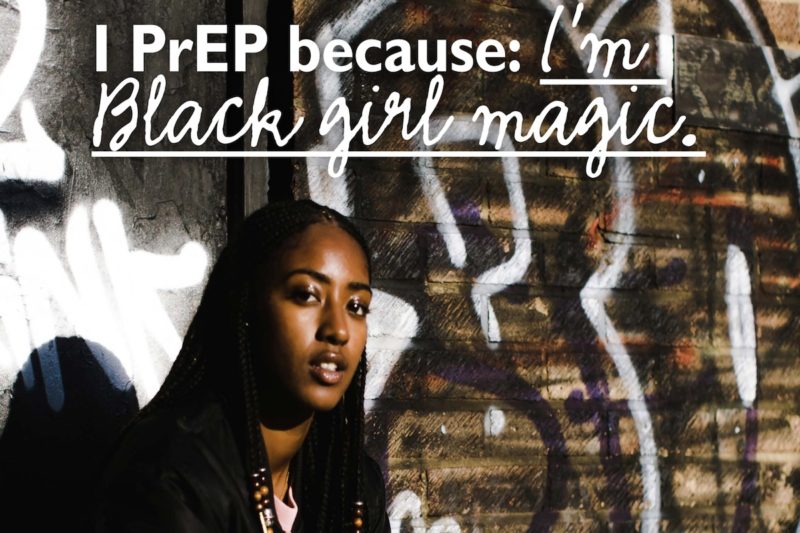

A Black woman with close-cropped hair and bright orange painted nails smiles confidently from a poster hanging inside a Planned Parenthood. Written above her image is the sentence, “I PrEP because: I’m Black girl magic.”

This poster—and alternative versions of it—appears in various health departments, universities, and faith institutions across the United States. Although the posters’ wording varies, their message is the same, bold and simple: Use PrEP.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a prescription drug, Truvada, that helps prevent HIV infection in people who are HIV-negative. If taken orally daily and as directed, it can reduce the risk of contracting HIV up to 92 percent, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The Black AIDS Institute designed the posters as part of its campaign to increase PrEP awareness among Black women.

Sixty-one percent of women living with HIV in the United States are Black, according to HIV.gov, and one in 48 Black women will contract HIV in her lifetime. These statistics underscore the risk to Black women and their partners.

Yet when it comes to PrEP prescriptions, 94 percent of its users in 2017 were men, according to AidsVu, a site that aims to make HIV data accessible.

“We spoke with a lot of Black women about using PrEP, and the majority weren’t aware of what it was,” said Fatima Hyacinthe, who leads the Black AIDS Institute’s PrEP campaign. “When we spoke with them about the information, a lot of women were upset that they weren’t aware of PrEP. They were upset that no one told them and that their doctors didn’t inform them on the choices they have to protect themselves.”

Since PrEP is either prescribed by a health-care provider or accessible through health departments, disconnects between medical staff and institutions are an issue for people who could benefit from it. In a 2013 study, three-fourths of U.S. infectious disease physicians surveyed agreed that PrEP should be available to some patients. But among all respondents, a third believed that PrEP was not relevant to their practices. Few had prescribed PrEP, which had just been rolled out by the FDA in 2012; many may have hesitated to push a new drug, and the CDC had not yet issued recommendations about its use.

And health-care providers—especially those who provide routine or primary care, such as the doctor who performs your annual physical—generally receive little training on how to elicit a comprehensive sexual history and help patients assess their risk. If medical professionals aren’t equipped to talk about sexual health, risk, or PrEP, their patients will miss the opportunity to learn.

That was borne out by the results of a 2015 study of almost 150 women considered high risk for HIV contraction. More than 90 percent of those women were Black, and only 10 percent of all the study participants had heard of PrEP, though they indicated a willingness to talk with their doctors about the regimen.

Hyacinthe of the Black AIDS Institute noted cost as another obstacle to PrEP use among Black women. While the cost of the pills are usually covered by most insurance companies and Medicaid (it can cost up to $2,000 monthly), those who take must do quarterly lab visits to monitor the body’s response to the medicine. And for those who have insurance, that still can mean out-of-pocket expenses. In that 2015 study, many women felt the cost of PrEP should be covered by public funds.

“When you’re explaining to people about everything that’s required when taking PrEP, it can start to sound pretty expensive,” said Hyacinthe. “If it’s already hard for someone to cover their co-pay, going to the doctor four times a year for lab tests may seem pretty expensive,” even for those with insurance coverage.

As with many health disparities, access to prevention and treatment is a complex issue. Black women have less access to insurance, specialty care, and are affected by racism, misogyny, homophobia, and transphobia.

“We have to stop blaming Black women for problems that are structural and systemic,” said Venita Ray, the deputy director of the Positive Women’s Network, an organization of women living with HIV in the United States.

Hyacinthe explained that one of the biggest problems regarding HIV and PrEP awareness is accessibility to communities that are majority-Black. Geography and racial segregation matter.

“You can look at a map of who is offering PrEP in San Francisco, an area that we know has a large population of people who identify as gay white men, and see a lot of places in which they can get information about PrEP,” she said. “If we look at Oakland, a community that’s only about 20 minutes away from San Francisco and is known as an area that has a high Black population, you will find very few places that people can go to for PrEP. That community needs the same amount of access to these services.”

AidsVu provides a location map of some of the health departments, clinics, and other institutions that offer PrEP around the country. The map currently has 1,800 locations and pulls data from the National Prevention Information Network’s directory of PrEP providers. While San Francisco lists more 30 locations people in the area can visit to receive PrEP, Oakland only has six.

“It’s not about just changing our behavior, and the problem just goes away,” said Ray. “It’s also about raising awareness and helping people to get a better understanding of the issue. It’s about getting better access to health care and educating more physicians on HIV and PrEP. There’s a lot more to it then just telling people to wear a condom.”

Promoting PrEP requires engaging not just doctors, but community networks and media. It was only earlier this year that the company that makes Truvada, Gilead Sciences, launched TV ads for the drug.

Leisha McKinley-Beach, a Florida resident who’s been working to raise awareness about HIV for almost 30 years, believes another factor contributing to the small numbers of Black women using PrEP is the stereotype that HIV is a white gay male issue. And that may extend to PrEP, if people think it’s only for white gay men, who have higher rates of uptake than Black gay men or Black women.

“Until recently, there haven’t been many visuals or information that suggested different,” said McKinley-Beach. “I remember when AIDS was first [portrayed] in the U.S. as a white gay male issue. [Due to that stereotype] I feel like the Black community had a ‘it don’t involve us’ attitude …. But it did involve us, and it was impacting our community from the very beginning.”

That’s why the Black AIDS Institute created the posters that are part of the Black Women and PrEP toolkit. They consciously picked images of Black women they believed to relatable, someone who looks like a friend or family member Black women might already know and trust.

“This series is created by Black women for Black women,” she said. “We wanted to make sure that the visuals and language we used in the material really connected with women.”

The stakes to reach Black women are high. Although the number of HIV diagnoses among Black women fell 20 percent between 2011 and 2015, the rate at which Black women contract it still far outpaces women in other racial groups.

That means Ray and advocates will keep centering Black women as they talk about HIV and PrEP.

“As a Black woman living with HIV, I don’t want to see another new diagnosis or another death related to HIV,” said Ray. “I want this all to end. I want the epidemic to be over.”