Mapping Out Missing and Murdered Native Women: ‘I Would Want My Story to Have Meaning’

The cartographer behind a new atlas project hopes it will provide an indigenous perspective of the milieu surrounding and contributing to the high rates of missing and murdered Native women and girls.

![[Photo: A crowd of people listen speakers raising awareness of missing and murdered Indigenous women]](https://rewirenewsgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/GettyImages-907790320-800x533.jpg)

Inspired by the Cheyenne concept of “netaevananova’htsemane” (which translates to, “let us recognize ourselves again”), Annita Lucchesi is working to create a mapping tool that recognizes and honors the geographies in which missing and murdered Native women live and die.

“Hand-drawn maps have great potential to reflect our ways of knowing,” said Lucchesi in an interview with Rewire.News.

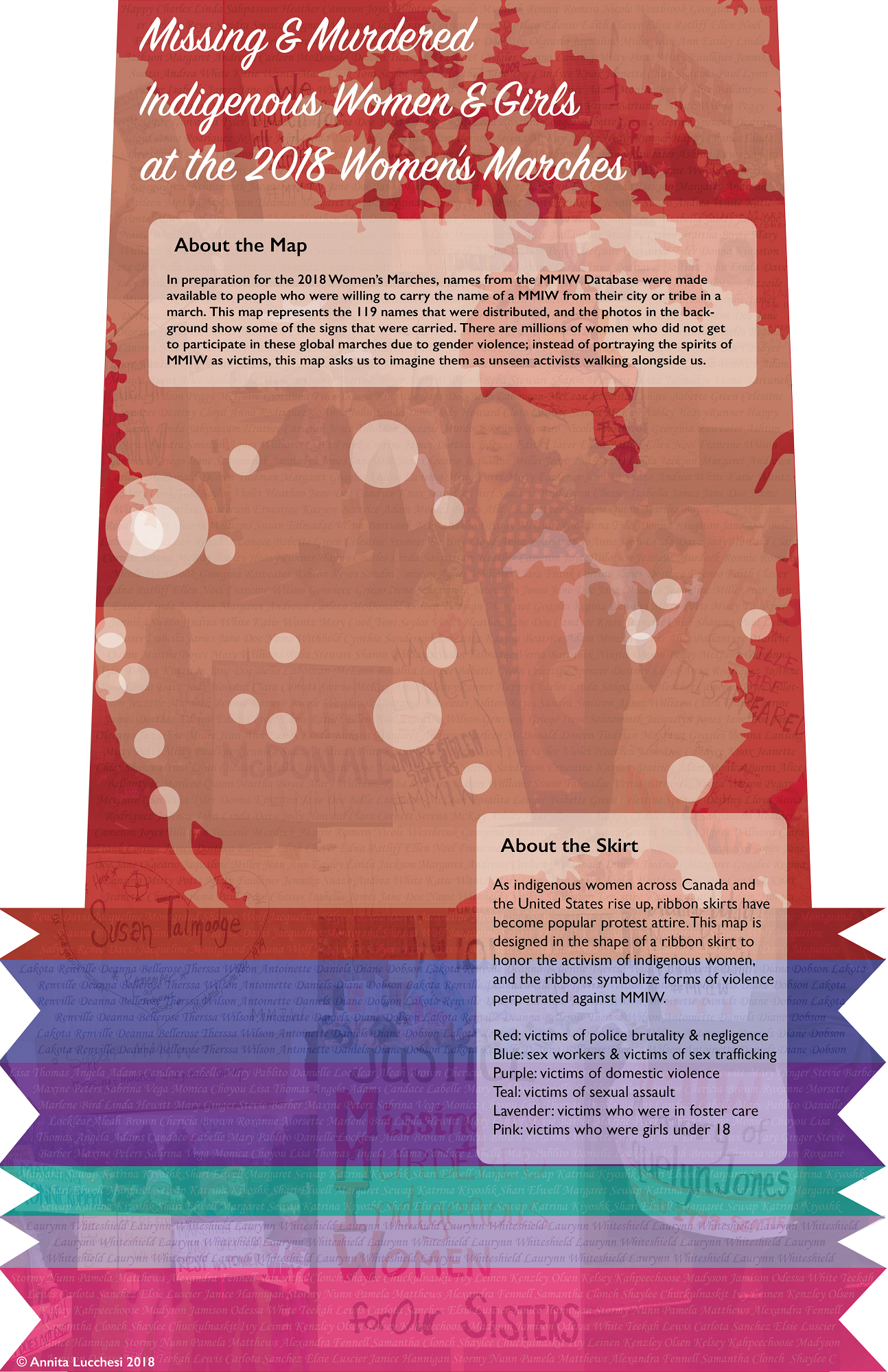

A recent example of this is a map Lucchesi created in preparation for the 2018 Women’s Marches. The map (shared below) features an image of a ribbon skirt, often worn as sign of respect and honor among Native women, with names of missing and murdered indigenous women incorporated into the design of skirt.

Using mainstream technology, Lucchesi seeks to infuse the work of the Atlas of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls in the United States and Canada with Native ways of thinking or epistemologies that are guided by community needs.

“Every element of the atlas is voluntary. My hope is that it will be a model to honor people dealing with these issues, by offering skills with which they can build the work themselves,” said Lucchesi. She added that “reducing peoples very real experience of violence into data points alone felt gross.”

A descendent of the Southern Cheyenne tribe, Lucchesi is all too familiar with the ways in which indiscriminate use and publication of such information can result in second-hand trauma for Native women. She hopes that the atlas will provide an indigenous perspective of the milieu surrounding and contributing to the high rates of missing and murdered Native women and girls and further empower communities to address the situation in their own ways.

Lucchesi, a cartographer and doctoral student at the University of Lethbridge’s Cultural, Social and Political Thought program, recently created and published an online database logging cases of missing and murdered indigenous women and two spirit people. She began gathering information for the database in 2015 from news articles, online databases, lists compiled by Native advocates and community members, family members, social media, federal and state missing persons databases, and law enforcement records gathered through public records requests.

She personally vets all information she receives before adding it to the database. Cases date from 1900 to the present; as of April 2018, she has found 2,501 cases of missing and murdered women and two spirit people in the United States and Canada.

There is no reliable national collection point or method to gathering comprehensive statistics on the number of missing and murdered Native women in the United States. This was emphasized in a 2015 series by Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting, which noted that there is no dependable national data source in the United States regarding missing murdered people or unidentified remains.

For Native people, available data is scattered throughout various tribal, federal, state, and other jurisdictions. Although the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NAMUS) functions as the U.S Department of Justice’s publicly accessible database, its information is dependent on data provided by various jurisdictions on a volunteer basis.

NAMUS does, indeed, provide a search option for missing persons by race, including Native Americans. Currently, NAMUS lists 102 cases of Native American women reported missing and 16 cases of Native American female unidentified remains—an undercount, as advocates have argued. Meanwhile, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released a 2013 report that found 1,181 missing or murdered Aboriginal females in Canada.

The results in NAMUS are especially unreliable for Native peoples due to the confusing question of jurisdictional reporting responsibility, which can include tribal, state, federal, or county agencies. For instance, tribal law enforcement agencies can take missing persons reports, but there is no guarantee that the report will be passed along to other agencies or be investigated. Tribal courts lack authority to prosecute major criminal cases and have limited resources for investigations. So depending on the state in which the tribe is located, either federal, county, or state authorities decide if they will pursue such cases.

Tribal and other police lose a great deal of time deciding which agency is ultimately responsible for an investigation. In missing persons’ cases, time can be of the essence.

Further, much about Indian Country falls outside of western-based data and information collection methods. Native people may be reluctant to report missing persons and communities may lack resources to investigate. Caught in a maddening Catch-22, Native communities are also typically on the bottom of the list for receiving federal and state support for infrastructure-building efforts, such as improving law enforcement and judiciary systems, which could help bolster data collection systems in the United States.

As reported in Rewire.News, generations of distrust among Native peoples for mainstream law enforcement agencies contributes to the lack of data.

“There is so much fear and distrust of law enforcement among our people that they are often reluctant to report loved ones as missing or to report sexual violence,” Carmen O’Leary, coordinator of the Native Women’s Society of the Great Plains in South Dakota, noted at the time. The Native Women’s Society is a coalition of Native programs that provide services to women who experience violence.

Police may be more interested in the criminal background of missing Native women than in working to find them; this creates a chilling effect on families’ likelihood of filing missing reports, according to O’Leary and other advocates.

Native people may also be reluctant to provide DNA samples for inclusion in federal databases. As noted in a 2015 article in the Atlantic, Native peoples have reason to be suspicious of Western based data gathering and research projects. “Native Americans … have witnessed their artifacts, remains, and land taken away, shared, and discussed among academics for centuries,” wrote Rose Eveleth.

Lucchesi is keenly aware of this exploitative history, and she doesn’t make the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) database information available in its entirety to all visitors to the site. She maintains the data via Excel spreadsheets with the help of volunteers. Potential users must first provide information on the type of data required, as well as their plans for using it.

For Lucchesi, navigating the material is a ceremony. “I think of navigating the data as prayer. Like ceremony, I have attached protocol in its use,” she said. “I don’t consider myself an owner of this information, but rather a caretaker. I want to ensure that women will be honored by the use of their data.”

Lucchesi asks those submitting reports of missing and murdered women to include greater depth of information than required by mainstream databases. For instance, the MMIW database includes tribal affiliation, an essential descriptor for Native peoples. Listings may also include information regarding life circumstances that may have led to victim going missing.

Although Reveal created what journalists there describe as a more streamlined tool to search for missing and murdered people, the program does not indicate tribal affiliation for Native subjects.

A Tradition of Map Making

Lucchesi is taking her perspective as a Native researcher to a new level in the upcoming creation of the atlas, an approved research project for her doctoral thesis.

Native communities, families, and advocates will determine the scope and use of the atlas, according to Lucchesi, who plans to bring the atlas project only to communities that reach out and ask her to bring the project to them. Waiting for an invitation from local people ensures buy-in and engenders a spirit of choice and empowerment. As word spreads that the atlas project is community-directed research, she hopes that more communities will participate.

After providing a brief history and explanation of the MMIW database and basic training in cartography, she wants to assist people in drafting their own MMIW maps. “You don’t need a lot of technical training and fancy software to create your own maps,” said Lucchesi, who plans to use an illustrator software rather than complicated Geographic Information System (GIS) technology.

In the institutional and academic traditions of cartography, scientists would often assume that indigenous mapping is non-existent, or, if it exists, is adapted from Western convention, according to Lucchesi. Western-trained cartographers assumed that Native peoples lacked the conceptual capacity to create their own maps.

She points to examples such as pre-contact Shoshone rock carvings as evidence that Native peoples have a long tradition of map making. When white settlers discovered the images created by ancestors of the Shoshone in Wyoming around 500 C.E., they viewed them through a European lens that sees art as primarily decorative. In recent years, archaeologists began asking help from local Shoshone people in understanding the images. The images make reference to contemporary Shoshone spiritual stories. These images may be maps of the spirit, guiding people in searches for guidance and the right relationship with their surroundings.

“Virtually no scholarship bringing together indigenous cartography and violence against women exists today. This is because cartography is dominated by white men who just never thought to address colonial gender violence,” Lucchesi said.

Rather than a singular map depicting incident locations, the atlas will include a collection of broad information depicting individual victim’s life paths and changes in their geography that put them at greater risk. For instance, atlas listings may include a history of family searches for victims and historical information about location from where a person went missing; location may be the area from which several other Native women have gone missing. Data points might also include background about what may have contributed to a victim’s involvement in risky behavior (if that is the case), such as history of sexual assault or the death of a child. Ultimately, community members creating the maps will determine the information that is listed.

The atlas will be publicly available online and hopefully in a book as well, explained Lucchesi.

A survivor of domestic and sexual violence, Lucchesi was almost a victim on the lists she maintains, she told Rewire.News. “If any of the men who almost killed me had succeeded, I would want to be honored and remembered. I would want my story and the violence I experienced to have meaning. I would want to be part of the fight for future generations of Indian girls not to have to go through such violence,” she said.

CORRECTION: The translation of the Cheyenne phrase in the piece has been updated.