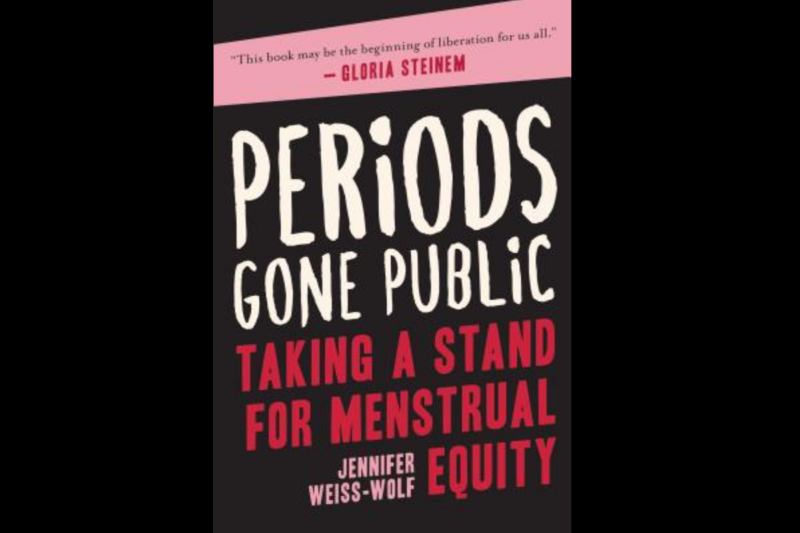

Menstrual Inequity Is a Global ‘Code Red Crisis,’ Says Book ‘Periods Gone Public’

On any given day, more than 800 million people are having their period worldwide. But far too many of them don't have access to sanitary products or facilities for hygiene or disposal.

In the patchwork known as the United States, each state has the right to decide which items to tax and which to exempt. In California, for example, there is a tax exemption for Pop-Tarts. In Florida, marshmallows are tax-free. Mississippi doesn’t tax coffins, and Maine gives Bibles a pass. The state of Wisconsin exempts some types of gun club memberships.

As reported by author, attorney, and menstrual activist Jennifer Weiss-Wolf in her book Periods Gone Public, products dubbed tax-exempt are a seemingly random and inessential lot. But turn to menstrual products, the pads and tampons used by more than half the U.S. population, and 37 states and many of the world’s countries impose a tax on them. About a dozen states—Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and Pennsylvania—have scrapped the tax.

Not surprisingly, such changes resulted from feminist organizing campaigns that have pointed out the arbitrary classification of menstrual products as taxable while exempting prescription drugs—including Rogaine and Viagra—as well as over-the-counter incontinence pads, dandruff shampoo, and lip balm from the tax collector’s reach.

It’s goofy. And it’s also unjust.

Weiss-Wolf interrogates this inequity, not just stateside, but in the lives of girls, women, and transmen across the globe. She further addresses how a “do-it-yourself” movement has emerged to provide affordable, and sometimes free, menstrual products to impoverished people in Central and South America; India; African countries such as Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda; and the United States. This movement, she writes, works in tandem with organizations that are trying to both demystify menstruation and dispel the stigma that has traditionally classified women as unclean during their cycles.

These themes make Periods Gone Public an uplifting read. At the same time, Weiss-Wolf does not sugarcoat the reality of patriarchal pushback or the problems caused by intense poverty, among them a lack of clean running water and a way to safely dispose of used menstrual products.

“On any given day,” Weiss-Wolf writes, “more than eight hundred million people are menstruating, and at least five hundred million of them lack adequate resources—including supplies, education, and facilities—for managing their periods.”

The upshot is sobering, if not shocking. In numerous countries, including our own, girls skip school when they have their periods. The reasons? For some, there is an inability to afford pads or tampons. For others, Weiss-Wolf explains—especially those living in the poorest corners of the planet—it’s a question of facilities. In those locales, she writes, “less than half of all schools and public places have working toilets.”

It’s a startlingly awful situation, and it’s not the only one Weiss-Wolf chronicles. Students in Bolivia, she continues, can’t dispose their used pads at school due to the widespread belief that bloody sanitary products can make people sick. Even more extreme, she writes that in parts of Nepal, menstruating girls are shut out of their homes and forced to dwell in isolated outdoor huts, no matter the weather.

“Entrenched stigma marginalizes menstruation and exacerbates the conditions of poverty, not only undermining the health and endangering the lives of women and girls, but also curtailing their opportunities,” she concludes. Weiss-Wolf calls it a “Code Red Crisis” and makes clear that it extends beyond the developing world to include low-income and transgender communities in Australia, Canada, the United States, and various European countries.

This reality, of course, is quite grim, but Weiss-Wolf does not languish in the negative. Instead, she turns to the many ongoing social change efforts that have emerged to put menstrual goods into the hands of those who need them.

She introduces Arunachalam Muruganantham, an entrepreneur living in the Southern India state of Tamil Nadu. “A high school dropout and son of a widowed mother, he is the creator of the world’s foremost menstrual micro-enterprise model,” Weiss-Wolf writes. After getting married in 1998, Muruganantham learned that a package of disposable pads cost 20 rupees, a sum equal to expenditures for three or four days of groceries. His wife, like other women in his village, could not afford this, so used rags that she hand-washed, but was too embarrassed to dry in the sun. As a result, Weiss-Wolf matter-of-factly reports that “the cloth was never fully clean, dry, or disinfected.”

This angered Muruganantham, and he decided to do something to make women’s lives easier. It took years—and included countless setbacks—but after a great deal of experimentation, he eventually perfected a machine that turned pulverized wood fiber into high-quality disposable pads.

Today, women’s groups, rural nonprofits, and job developers use Muruganantham’s device to make pads, which they sell for a fraction of the cost of corporate-made products. What’s more, one machine can make up to 100,000 pads a year and provide an income for 10 workers. Not surprisingly, more than 4,000 Muruganantham-inspired production centers currently exist in India and elsewhere.

Numerous other entrepreneurial models have also been developed, including Rwanda’s Sustainable Health Enterprises (SHE), which utilizes banana trunk fibers to create eco-friendly pads, and Femme International, an East African group that partners with local schools to run workshops on menstrual health. Additionally, SHE provides students with menstrual cups, reusable pads, and soap, a towel, and a steel bowl for boiling water and sterilizing materials. This enables them to take the precautions necessary to avoid toxic shock syndrome and infections that can result from reusing contaminated goods.

Weiss-Wolf writes that stigma-busting often goes hand-in-hand with product creation and there are innovations here, too. Writer Aditi Gupta developed a series of graphic novels called Menstrupedia, intended for adolescents and filled with concrete information about menstruation, self-care, and how best to help a friend or family member when she has her period. Since launching in 2014, the books have been translated into 16 Indian languages as well as Russian and Spanish. Similarly, a UNICEF team in Indonesia has launched a widely-distributed ten-page comic for teenage girls and boys to educate them about reproductive health, with a focus on menstruation. Similarly, in Madagascar, a video called Girls Just Wanna Have Pads (yes, it’s a nod to Cyndi Lauper) is shown in middle schools and combines information on sexual health with the provision of washable sanitary pads, a cycle-tracking calendar, and a carrying case.

In the United States, efforts to remove the tampon tax are ongoing, and feminist organizers continue to push for free pads and tampons in all public schools, homeless shelters, jails, and government buildings, with a goal of making them as available as toilet paper, soap, and hand towels. Activists are also working to allow food stamp recipients to use their benefits to purchase sanitary goods and provide WIC recipients with menstrual supplies alongside supplemental food and nutritional resources.

All told, Weiss-Wolf maintains that providing free tampons and pads is in the interest of public health and safety. It is further noteworthy that she stipulates that both women’s and men’s bathrooms should be stocked to accommodate transgender individuals. “A holistic agenda for menstrual access must include trans people who are dealing with periods in some of the most difficult and dangerous circumstances,” she concludes.

In fact, despite the ongoing domestic brouhaha over bathroom access, Weiss-Wolf maintains that menstrual equity has broad bipartisan support throughout the United States and is a winnable issue if we mobilize and demand it. She maintains that we can not only win removal of the tampon tax in all 50 states, but also provide free sanitary supplies to students, the homeless, prisoners, and the poor as a matter of course.

Nonetheless, when it comes to strategy, Weiss-Wolf advocates severing reproductive justice from menstrual equity—a position that is certainly ripe for debate. As she sees it, because menstrual equity can be presented as a matter of public health, it sidesteps the controversy that typically surrounds other reproductive justice issues, from abortion to sex ed. There is something to be said for the pragmatism of working incrementally, but in the long-term, I think this stance is a tactical mistake since if we demand less than we need, we’ll likely win very little. But no matter where you stand on this, Periods Gone Public is eye-opening, fascinating, and simultaneously practical, enraging, and encouraging.

It also touches numerous themes that can be further developed, from how to encourage greater use of reusable products to how best to incorporate menstruation into a sex education curriculum that goes beyond nuts-and-bolts to address the idea of gender itself. Weiss-Wolf has left these doors ajar; it’s now up to us to push through them and organize our communities for meaningful menstrual equity.