What Happens When DACA Goes Away? Immigrant Youth Share Their Stories

In their own words, ten young adults share their experiences with being protected by Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA): what it has meant and where it has fallen short. "DACA may end, but our focus to protect our community will not," 19-year-old Samuel Cervantes told Rewire.

Read more personal stories from DACA recipients here at Rewire.

In the days following President Donald Trump’s inauguration, there were whispers he would do away with the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. In anticipation of such a blow to young immigrants nationwide, I put out a call on social media, asking DACA recipients to share their stories with me: What was life like pre-DACA? How did DACA change their personal lives, their families’ lives, their community? What would happen if DACA was taken away?

The Obama-era immigration program has drastically changed the lives of an estimated 800,000 young people who because of DACA, can legally work, drive, and travel abroad. Perhaps most important of all, it has meant they have not had to fear deportation—until they had to renew their status.

Fears that Trump would end DACA were assuaged in February when he promised to “deal with DACA with heart.” In the meantime, Trump and his administration have used their authority to make the 11 million people in the United States without authorization deportable. Then-Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security John Kelly signaled in May that Haitian immigrants will no longer receive temporary protected status after January 2018, despite an ongoing cholera outbreak in the country. Trump endorsed a bill in Congress earlier this month that would drastically limit “legal immigration,” shattering the primary pathways Black immigrants use to come to the United States. And Attorney General Jeff Sessions has hammered away at so-called sanctuary cities, emboldening other anti-immigrant lawmakers like Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R), who signed SB 4 into law in May. SB 4, which a federal judge temporarily blocked a day before it was set to take effect, allows law enforcement to racially profile people for the purpose of detainment and deportation. But still, Trump had left DACA alone.

This program is now in jeopardy in real ways. Ten states have threatened to sue the Trump administration if it doesn’t rescind DACA by September 5. There are rumors Trump is willing to throw DACA recipients under the bus for additional border wall funding, as he may have done to transgender people serving in the military and disaster relief funds. ABC News has reported that Trump will end DACA this week.

As of publication, Fox News is reporting he will end the program as it currently exists, though there is no official statement from the White House as of yet supporting that claim. Many of the DACA recipients who shared their stories with Rewire expressed that this uncertainty is perhaps the worst part of all of this, as the president is seemingly unaware that the livelihoods of 800,000 young people are hanging in the balance. Rewire will continue to collect narratives from DACA recipients. Those interested in sharing their stories can contact us here.

In their own words, here are some thoughts, concerns, and stories from some of the nation’s DACA recipients.

Name: Manuel Vasquez

Name: Manuel VasquezAge: 27

Location: Raleigh, NC

“I first learned about DACA when Obama made the announcement five years ago. I was in a group of friends who were active in the immigrant rights movement and posted updates about it. I applied immediately, and got it when I was around 22.

“I grew up with people who were active in the immigrant rights movement and that was really empowering for me, so there wasn’t anything I was really afraid of. I felt like I had people in my life who had my back, and that helped a lot.

“When I was younger, before DACA, I was very careful about not staying out too late, not driving past certain times, or driving on weekends because of police. Now I have a license. My family is undocumented, so I’m the one who does the driving, the long-distance driving when we visit family. It’s a small piece of paper, but it allows me to get through airport security without problems. It allows me to drive my family without fear. For me, it’s this small stuff that people don’t necessarily think about, everyday life stuff, that DACA has helped.

“Even from the beginning, people in my community felt DACA wasn’t anything permanent. I mean, we have to renew it, but I always felt like there was a possibility it would end. It’s never felt like a permanent solution. Right now, it’s just up in the air in a different way. As a community, we need to be ready for whatever happens and figure out our next steps.

“Because of having DACA, I personally feel like my life has been in a place of privilege. I have something people in my family don’t have. If this all ends tomorrow, I know I have a support group around me, friends in the immigrant rights movement who work to make things better. There are people in the [undocumented] community who don’t have that, who don’t have that support group and rely on DACA completely.

“The main thing people should know is that from the beginning, DACA wasn’t a final solution; it was a Band-Aid. We were asking for a pathway to citizenship, DACA is not that. I’ve heard people refer to DACA as all kinds of things—as amnesty, as the DREAM Act. It’s not those things either. If this gets taken away, we need to keep the pressure on for more and for better.”

Age: 19

Location: Texas

“I am a sophomore at the University of Texas double majoring in government and communications. When DACA was introduced, I was a freshman in high school. The idea of having a work permit and not fearing deportation was comforting, and the access that DACA has allowed me has been critical and indispensable. I could finally relate to all the activities my friends were enjoying: I was able to obtain a driver’s license in Texas, work my senior year of high school, and travel outside of Texas. But ultimately, DACA has a been a vehicle to attend college. DACA was not a solution to my status; it is merely an ephemeral period of comfort—a period of time where I have enjoyed the privileges for which my parents came to this country. If Trump ends DACA, I fear for not being able to financially support myself while living in a different city than my parents. There is a psychological and emotional toll of having to be vigilant of my surroundings and to calculate my every move to not be at the wrong place during the wrong time. But as my father would say, Ponte las pilas y echale ganas. DACA may end, but our focus to protect our community will not.”

Name: Yosimar Reyes

Age: 28

Location: Los Angeles, CA

“My greatest concern over DACA being repealed is that for many of us, we are the only ones with a work permit. Taking this permit away from us has a greater effect on our families since we cannot continue to support them. I am scared that without a work permit, I will not be able to help pay my grandmother’s rent.”

Age: 21

Location: Austin, TX

“I’m a chemistry senior at UT Austin and part of the University Leadership Initiative where I have been part of the team that implemented DACA educational forums and DACA clinics to help families fill out and prepare the application. I received DACA in 2012, and having a work permit enabled me to drive with a license and no longer fear a police officer pulling me over and questioning my status. DACA also allowed me to obtain a social security number [and] to be employed by UT Austin. A part-time job gave me the economic freedom to no longer be a burden on my parents. DACA has allowed me to safely travel within the United States without fear of being stopped at security gates. DACA has allowed me to independently finance and continue my undergraduate career. Terminating DACA will put many professional, college-educated individuals on an uncertain path where they can no longer give back to their own country—by working and paying taxes in this economy.”

Name: Alexa

Name: AlexaAge: 28

Location: San Bernardino, CA

“My biggest concern isn’t for me; it’s for my sister, who is supporting her two small, American daughters who depend on their undocumented, hard-working mother who has DACA. I’ve always made it as undocumented because I didn’t have someone depending on me to provide shelter, food, and an education. It would break my heart to see my sister lose her job she’s worked so hard to have and have to worry about how to keep her family afloat.”

Name: Nanci Palacios

Age: 28

Location: Florida

“I was one of the DREAMers who fought for DACA and when it passed, I considered it an organizing victory for the undocumented community. I still remember getting a call from a national organizer who knew DACA was happening prior to Obama making the official announcement. I applied the day it went into effect: August 15, 2012. Since then, I’ve renewed DACA twice.

“Because of DACA, I obtained a job where I do what I love: Organize communities that are marginalized and vulnerable. This job gives me benefits and health care, and I can support my family. I’m the main means of support in my family and I’ve helped my parents buy their first home. I finally have a car and I was able to re-enroll into college. I’m paying for college out of pocket, but this job has ensured I can pay for my college degree. With DACA’s advanced parole, I was able to visit Mexico for the first time in 20 years and see my grandma and my mom’s side of family. Traveling has been so fulfilling. I’ve been able to do things and go to places I could have never imagined. DACA has given me the ability to envision this life I could have if I had a permanent status. DACA has its restrictions, but it’s showed me the possibilities.

“Before, I was fearful. I was driving without a license. I was never sure if I’d have a job. I was living in a mobile home with three siblings and my parents, all of us compacted into a two-bedroom mobile home where we were constantly threatened with eviction because we were undocumented. Despite paying our way, my family never had anything they could call their own. DACA has given me this freedom of being, of existing, of driving—and now once again, we’re being confronted with uncertainty again. We don’t know what today or tomorrow will bring. It’s a huge burden, not just for myself, but for my family, for our communities.

“If DACA is phased out, I have a year to reconfigure my whole life. My work permit and license would expire in October 2018. I’m two semesters away from graduating. If I knew DACA was going away, I couldn’t use any of my money to continue my education because my priorities will have to shift. My fear isn’t being undocumented again. I know what it’s like to live that way; I’ve done it before and I know I can do it again. We are survivors. But it’s more the feeling that we’re being played with. DACA provided this glimpse into a different life, and it’s going to be taken away. We’re being used as a bargaining chip for someone to fulfill their own agenda, and it’s not the first time this has happened to undocumented communities. What about all of the money we have paid into this country as DACA recipients? We’ve kept social security alive, and we don’t get that benefit. Do we get that money back?

“It doesn’t hurt anyone to allow us to have DACA, and now we are priorities for deportation. That’s something I am fearful of. The administration—because of DACA—has my data; they have my personal information and the information of every DACA recipient. It’s a lot to process. But they won’t instill fear in me. I won’t crawl back into the shadows. We won’t crawl back into the shadows.”

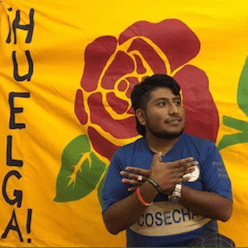

Author’s note: Catalina Adorno, Miriam Zamudio, Catalina Santiago, and Jose Luis Santiago are members of Cosecha, a non-violent movement that fights for the rights of the 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S. These young people are taking part in what they are calling “the largest immigrant-led action” in the country to fight for undocumented immigrants and DACA and TPS recipients with student walkouts planned for September 1 and mass, nationwide protests September 5.

Name: Catalina Adorno

Name: Catalina AdornoAge: 27

Location: Union City, NJ

“I was born in Puebla, Mexico, and came to the United States when I was 9 years old. I have been living in New Jersey for the last 17 years, and have not been to Mexico ever since. I am taking action because I am angry that my community continues to be criminalized. Five years ago I applied for Deferred Action, also known as DACA. Although I received a work permit and a social security number, many loved ones did not, because they didn’t qualify. They were not deemed ‘worthy.’ I saw how although I now had some sort of temporary protection, many loved ones did not. I’ve had enough. I’ve had enough of our community being treated inhumanely. All of us, all 11 million undocumented immigrants, deserve permanent protection, dignity, and respect.”

Name: Miriam Zamudio

Name: Miriam ZamudioLocation: Perth Amboy, NJ

Name: Catalina Santiago

Name: Catalina SantiagoAge: 20

Location: Homestead, Florida

“I am engaging in this civil disobedience to honor my parents’ labor. My parents are one of the most vulnerable workers in this country— they’re farm workers. We migrated from Oaxaca, Mexico, to Homestead, Florida, in 2005. I am standing up for myself and all the 11 million undocumented people. I am fighting back as a small way of honoring the sacrifices that my parents have made, starting with crossing the border and them having left so much in our home country, Mexico. I’ve spent more than half of my life in the United States, missing so many festivals, births, and the death of my paternal grandfather has made me angry. I am going to continue fighting to honor the risks of those undocumented youth that took action to win small victories because the temporary protections were not just handed down to the community.”

Name: Jose Luis Santiago

Name: Jose Luis SantiagoAge: 21

Location: Florida City, FL

“I came to the United States of America at the age of 9. I have been living in Florida City, Florida, for most of my life. That’s where I learned to read and write. That’s where I learned to ride a bike and drive a car. That’s where I have my family and friends. I recently graduated from Miami Dade College with an associate of arts degree. That’s where I want to stay. My family is a motivation for me to participate in Cosecha; it’s not right to deport people and separate families and I am not willing to wait until they attack my family to stand up and do something about it. The message I would like to give to the general public is that you need to join us in making sure this country recognizes and acknowledges its dependency on immigrants like my parents, who have contributed so much to this country.”

Please contact us here to share your story.