D.C. Metro Rejects Medication Abortion Ads

“Part of what Carafem wanted to do was to speak openly and unapologetically about abortion in the same way that other providers speak about their services,” said Melissa Grant, Carafem's vice president of health-care services. “This feels like a First Amendment issue .... It feels wrong.”

A reproductive health center said the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) is censoring the company’s messages about medication abortion by selectively enforcing its advertising guidelines.

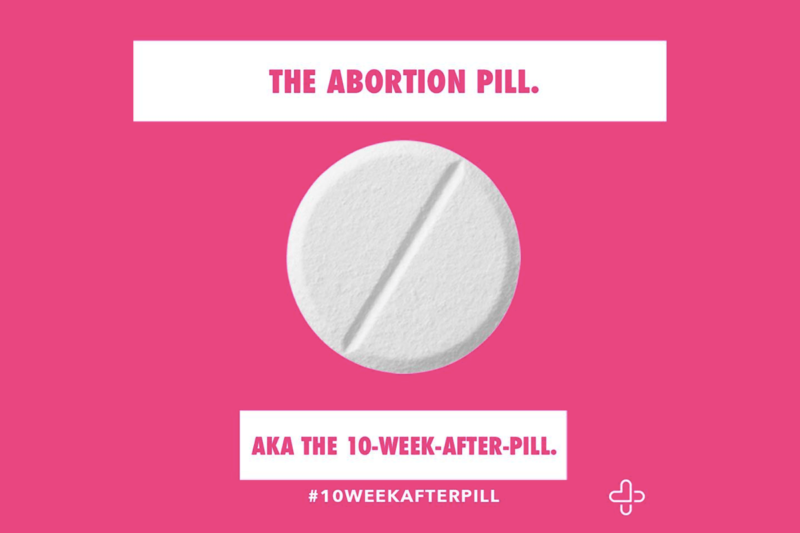

Carafem, which has offices in the D.C. area and Atlanta, planned to spend $23,520 to erect bold pink signs in WMATA train stations as part of its new “10-Week-After Pill” ad campaign.

The effort focuses on promoting the medication, which consists of two different pills—mifepristone and misoprostol—taken in sequence to terminate a pregnancy up to ten weeks.

Carafem officials said the campaign will contribute to public education about the differences between the ten-week abortion pill and emergency contraception, which is only effective up to 72 hours after unprotected sex.

WMATA rejected Carafem’s ads last month, claiming that the messages violate advertising guidelines. Spokesperson Richard Jordan told Rewire in an email that the medication abortion ad was declined because it makes a “medical statement in violation of WMATA Commercial Advertising Guideline 4, which only permits these kinds of statements as provided by or approved by government health organizations.”

The ad also violates WMATA’s advertising guidelines because it “attempts to influence members of the public regarding an issue on which there are varying opinions,” he said.

Researchers have proven the safety of medication abortion, which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). A study released in 2012 found that less than 1 percent of the 233,805 pregnant people that received medication abortion at 317 Planned Parenthood offices experienced a serious side effect or a failed abortion.

The WMATA board in November 2015 adopted a resolution prohibiting commercial advertising for “issue-oriented advertisements, including, but not limited to, political, religious and advocacy advertising.” The ban was instituted after the American Freedom Defense Initiative, an anti-Muslim group, sought to erect ads in Metro train stations, the Washington Post reported.

Carafem successfully ran ads at Metro stations in spring 2015 after opening its office in Chevy Chase, Maryland. But when the company tried to launch a second ad campaign that October, the ads were rejected—a decision that WMATA claimed was a misunderstanding.

WMATA has since reversed its stance again, saying that allowing the Carafem ads to run in late 2015 was an error, the Post reported.

Melissa Grant, Carafem’s vice president of health-care services, told Rewire in a phone interview that the health center did not communicate with WMATA after it passed the 2015 resolution. Previous ad campaigns had been allowed, and so Grant did not anticipate a problem.

“This is the first time we’ve had a clear and firm refusal,” Grant said.

Grant said the company’s legal representative reached out to WMATA last week to question the agency’s decision. A few days earlier, Carafem told the Washington Post it had not ruled out taking legal action against the transportation agency.

“Part of what Carafem wanted to do was to speak openly and unapologetically about abortion in the same way that other providers speak about their services,” Grant said. “This feels like a First Amendment issue … It feels wrong.”

Grant said the ads are not political and are like any other health-care advertising commonly seen inside Metro train stations.

Carafem noted in a blog post that WMATA had allowed a Doctors Without Borders ad about vaccinations as recently as January 5. Other recent signs include a MedStar Georgetown University Hospital ad on prostate cancer treatment and ads from national nonprofits and local health centers such as the Alzheimer’s Association, Reston Hospital Center, and the Virginia Spine Institute.

“Refusing to run ads for abortion services, despite the fact that nearly 1 in 3 women will have an abortion at some point in their life, adds to the stigma associated with abortion. Picking and choosing which health conditions or treatments are okay to advertise is censorship,” Carafem published on its blog.

Donna M. Murray, manager of advertising and market development for Metro, told Carafem in an email that the ads qualified as issue-oriented because they addressed “the controversial topic of abortion,” the Washington Post reported.

Murray added that WMATA will only accept health-related ads from “government health organizations, or if the substance of the message is currently accepted by the American Medical Association and/or the Food and Drug Administration.”

The medication abortion pills Carafem is promoting, however, are recognized by the FDA.

Grant told Rewire that D.C. Metro stations were critical to the ad campaign, allowing the health center’s message to reach a high volume of D.C. residents. The D.C. Metro has 91 metrorail stations, and more than 700,000 people use the Metro every weekday.

While WMATA rejected Carafem’s ad campaign promoting the“10-week-after pill,” the ads appear in bus shelters operated by the District Department of Transportation. The ads also will begin appearing on panel truck billboards throughout the D.C. area from January 19 to January 21, Grant said.