‘Overworked and Underpaid’: On Organizing, Black Womanhood, and Self-Care

Accolades and honors do little when a culture of martyrdom—the discouragement to prioritize one’s own emotional and mental health—reigns in the lives of activists.

This piece is published in collaboration with Echoing Ida, a Forward Together project.

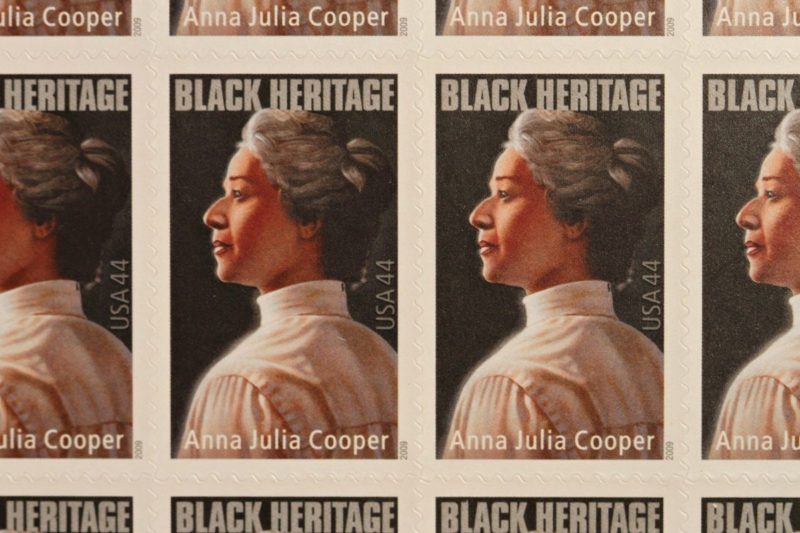

As a researcher, I am interested, indeed positively obsessed, by the long tradition of Black feminist organizing in the United States. Outspoken activists like Ida B. Wells, Anna Julia Cooper, Fannie Lou Hamer, Toni Cade Bambara, and Frances Beal embodied their values to center the voices and thought leadership of Black women. They wrote and delivered speeches about the duality of sexism and racism Black women encountered in this nation, garnering in some cases accolades and honors.

But awards do little when a culture of martyrdom—the discouragement to prioritize one’s own emotional and mental health—reigns in the lives of activists.

I have found in my research that not much has been written about how women of color organizers made space for joy, wellness, and love while fighting against white supremacy and other forms of oppression. With activists today facing a similar struggle, I wanted to know what could we learn from our Black women activist foremothers to avoid burning out.

So I went to the archives—that special place where I could touch a letter or a newspaper. At the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, I examined Triple Jeopardy, the 1970s newspaper of the Third World Women’s Alliance, a radical women of color organization. I saw themes of struggling against oppressive structures and the fatigue that often accompanied the work. For example, the committee responsible for editing and publishing Triple Jeopardy described themselves in the last two editions as “overworked and underpaid.”

Similarly, during archival research at the Spelman College Archives, I came across a letter from writer-activist Toni Cade Bambara to writer-activist Audre Lorde, in which the closing simply, yet very tellingly, read “overwhelmed Toni.”

For me, this admission that they were tired, human, and affected by the oppressions they fought makes room for Black women to name their feelings and share their stories. That vulnerability and space needs to be continuously created because it would allow us to express that we are in need of change, and in need of assistance as we work under multiple pressures—deadlines, limited resources, the constant hovering of oppression, and age-old representations of Black womanhood.

The “Mammy” trope—which depicts Black women as perpetual, asexual servants loyal to white supremacy—is particularly damaging to Black women. It holds that Black women are happiest when they are serving others, which means that they all too often are expected to delay their own self-care and joy. This trope gained popularity in the 19th century, but its remnants remain with us as Black women continue to be thought of as strong. If we take the Mammy trope as an example, a Black woman’s only role is to be in service to everyone outside of herself. Black women activists then become the depository for any affliction that ails people.

Many Black women have tirelessly fought to resist ascribed roles.

Triple Jeopardy and the letters of Bambara and Lorde taught me that Black women used activism and writing as forms of self-care. Self-care is antithetical to the Mammy trope, which represents Black women as self-sacrificing. Black women’s ability to write each other, about their personal, creative, and organizing lives, was deeper than just catching up. Letter writing served as a tool of survival, as the authors reimagined their lives as Black women. They also supported each other, as they provided feedback on each other’s poems and stories; they uplifted each other, and made plans for meetings and celebrations.

Many of the letters I came across in the collections of Bambara and Lorde expressed gratitude to the sender from the recipient whose spirits were lifted after receiving a personal letter. “I got your lovely card, and it picked up my dropping spirits—just like your fiction does,” scholar Mary Helen Washington wrote in a letter to Bambara. In another letter addressed to Bambara, the writer (signed only as “G”) said, “Girl—I just got your letter—and was it ever on time.”

Black women writer-activists also did some form of consciousness-raising via letter writing. They expressed rage and humor at the audacity of people, mostly white male publishers, trying to define them through a white, masculinist, and heteronormative lens. And they sought understanding and reconciliation from each other as Black women and feminists.

In a letter to scholar Evelynn Hammonds, Lorde writes:

Please forgive the delay in this reply to your letter…I wanted to think about issues you raised in your letter reaching beyond the material ones…Evelynn, it is not clear to me the exact nature of the conflicts underlying the history between you and Barbara and Cherrie, nor does it need to be. But the bitterness on both sides is quite obvious…I do not like this. It makes me very sad because I feel it is unnecessarily destructive for us all. We have so little time, and there are so few of us doing real work, and under so much pressure…I ask you to consider: WHO PROFITS FROM THESE SEPARATIONS BETWEEN US, THESE ACRIMONIES, THESE FEUDS? So, I am wondering if there is any way possible for each of the three of you, having been separate now for over a year, to re-examine your relationship to the personal conflicts between you…and consider what some of the real bases are upon which you can deal with each other with some amount of respect and trust?

They gathered strength from each other as they talked of how things are, and how they wanted them to be.

These letters challenged the narrative of the strong and ever-enduring Black woman. They serve as an example of the importance of quality of life for activists, and how they can best be supported.

In order to have sustainable movements, social justice movements and organizations need to center the care of activists.

Organizations and movements can make sure that they are creating space for self-care by prioritizing wellness, and encouraging activists and movement builders to take the time to do the same. I know that the work to destroy all forms of oppression requires all of our time. We are, after all, fighting to bring about a more just and equitable society. However, it is possible to do the work and prioritize health and wellness at the same time.

I know that conversations around self-care can sometimes be elitist and classist. Yoga classes can cost an average of $18 per session, and massages sometimes start at $70. Self-care can quickly become about who can afford to relax and release some tension. But costs don’t necessarily have to be a barrier to relaxation.

Community care is essential to the lives of activists. Activists and organizations can host massage and healing circles, journal together, check in with each other regularly, and seek authentic and honest relationships that affirm them. Instead of being seen as more work, this actually can be an essential part of a wellness routine that can aid activists in their work.

Love for each other, and an investment in our individual as well as collective needs, will help us as we navigate and work to dismantle hostile environments. Activists can encourage each other to take care of their emotional, spiritual, mental, and physical selves. Managers and executive directors can create wellness as part of work culture by checking in with their employees. Some already do. I hope others will catch on.