Sorrow Like a River: Forcing the World to Listen

Advocates like Miller Tanner, the Wiyabe Project, and the Sing Our Rivers Red group are building a wave of resistance to the longstanding indifference surrounding missing and murdered women in their communities.

This piece, the third installment, was cross-posted from Indian Country Today with permission as part of a joint series about the missing and murdered Native women in the United States and Canada. You can read the other pieces in the series here.

Most advocates for missing and murdered Indigenous women are motivated by the loss of a family member or friend as well as ongoing stories of loss in their communities.

When Makoons Miller Tanner works on her volunteer blog, she often thinks of her grandmother, who passed away in the 1940s, long before she was born. “She was in her 20s when she was killed. The authorities declared her death to be the result of her hitting her head on a rock after a seizure. This for a woman with no history of a seizure disorder,” Miller Tanner said. “She hit her head on that rock nearly 75 times.”

Her family still speaks of the hurt and anger over the injustice surrounding her grandmother’s death. After hearing the story repeated many times, she grew determined to contribute somehow to helping others find justice for their loved ones.

“Her story has been an inspiration for me to keep going,” said Miller Tanner.

She began keeping her blog in December 2015 and has completed almost 200 profiles of missing/murdered Native women in the United States and Canada. During the course of the work she has noticed that if Native women have any sort of criminal history, they don’t get treated as deserving victims.

She also noted a tendency to disregard spates of murders if police determine that they were not the work of a serial killer. “It’s like there is less danger to the broader community. It’s just Indians drinking and killing each other; it’s business as usual,” she said.

Advocates like Miller Tanner, the Wiyabe Project, and the Sing Our Rivers Red (SORR) group, however, are building a wave of resistance to the longstanding indifference surrounding missing and murdered women in their communities.

SORR with its symbolic focus on the Red River, which flows north from the United States to Canada, has helped unite Indigenous peoples from both countries in their common concern over violence against women in their communities.

In 2014, seven bodies of indigenous women were found in the Red River, which flows through Winnipeg.

The Red River has become the most recent focal point of the missing and murdered Indigenous women issue in Canada. Volunteers have organized to drag the river, hoping to find remains of some of the dozens of women reported missing each year in Canada.

Winnipeg police, however, declined to help these efforts, calling them inefficient allocation of law enforcement resources.

With the help of public donations, families, friends, and supporters banded together and dragged the river, desperately hoping to find clues to the whereabouts of loved ones.

According to advocates such as Clinton Alexander, director of the Native American Center of Fargo, secluded spots along the river in and around Fargo are known as dangerous places for Indigenous women.

Located in east central North Dakota and close to bordering Minnesota, Fargo is a well-known stopping off place for Native peoples enroute to the various reservations in this vast area.

Native people make up a large portion of the homeless population here. “People turn a blind eye to violence that occurs among a population that they see as marginal. There’s an attitude that women who are on the streets are ‘bad victims’ and don’t deserve help and support,” he said.

Alexander said that systematic and collective racism among the community and law enforcement contributes to Native women’s fear of reporting sexual assault. As Jacqueline Aqtuca of the National Indigenous Women’s Resource and U.S. Associate Attorney General Thomas Perrelli of the Department of Justice have noted, unrecorded sexual violence directly contributes to increased incidents of women going missing.

“We encourage them to report the incidents to police but they say, ‘What’s the point? Police won’t do anything.'” Alexander said.

Alexander described a case in which a Native woman in Fargo, North Dakota, flagged down police after her friend was sexually assaulted only to be arrested for public intoxication herself.

He also told of going to the emergency room with a Native woman who had been raped. “She didn’t want to make a police report, she just wanted to be examined and get Plan B contraception,” he recalled.

The police officer at the hospital insisted on being present in the room despite being told the victim didn’t want him there and the case was a “Jane Doe” report. In such reports, victims do not have to agree to immediately press charges against the perpetrator; they can do so at a later date.

“The woman was very traumatized by her treatment at the hospital. Law enforcement sent the message that she couldn’t be trusted. In the end she chose not to press charges,” he said.

“Native women are afraid to report rape. They say it’s like being victimized all over again,” he said.

Cathy, who requested only her first name be used, described how she was raped and sodomized under the Veterans Bridge in Fargo last year.

“It was still daylight,” she recalled.

After 11 years of sobriety, she had relapsed and was drinking with a man who she thought was her boyfriend. She had passed out under the bridge but woke to find him and another man assaulting her. “I tried to get away but they held me down. [The ‘boyfriend’] said he would tell my family I was working as a prostitute if I called the cops.”

She was not but knew police would be unlikely to take her report seriously. “I knew that since I was using, the cops wouldn’t do anything, so I didn’t report it,” she said. “The cops don’t have time to listen to you, they say, “Oh, you’re just another drunk Indian, take her to detox,” she added.

Cathy sometimes blames herself for her attack but added, “It shouldn’t matter what kind of shape I was in; I didn’t deserve that.”

Cathy is currently in a nursing home in Duluth recovering from an accident and hopeful she can “get back on track.” In the meantime, she said, “I have a hard time sleeping at night; I need to have all the lights on.”

Advocates such as Alexander and organizers of the Sing Our Rivers Red project fear that the number of missing, murdered, and assaulted Indigenous women may also be far higher than official data indicate.

Tanya Red Road, program coordinator for the Fargo Native American Center, reported that she receives several calls each week from people seeking information about missing women from all over Indian country. “So many people are searching for missing loved ones,” she said. “We take their names and promise to keep an eye out for them.”

SORR organizers have created a display of over 1,000 single earrings sent to them by volunteers to honor the missing and murdered. The display, which includes information about the issue both in the United States and Canada, is available for display to communities.

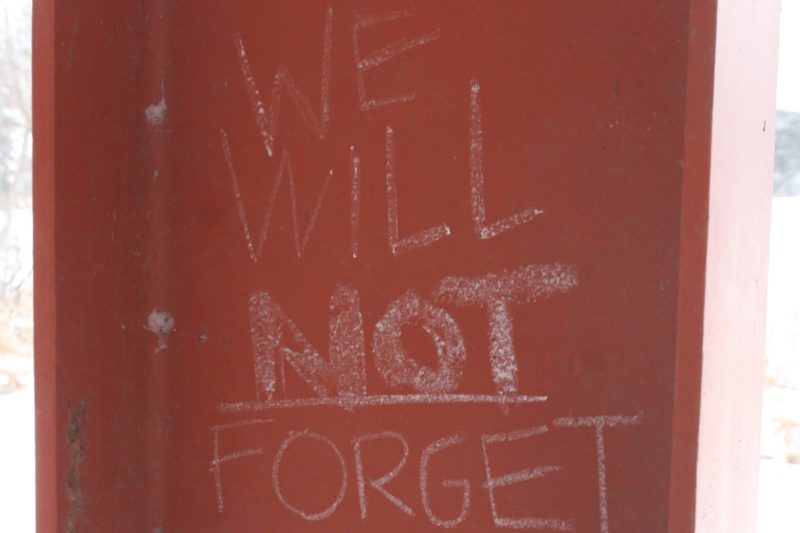

Although their numbers were small, local Indigenous women and supporters marched in solidarity with their sisters in Winnipeg to bring attention to the unreported violence against Indigenous women. During a stop under the Veterans bridge, elders held a brief ceremony on that icy Valentine’s Day. SORR organizer Hannabah Blue said, “We are letting the perpetrators and community know that we are watching.”