‘Winning Lies Not in a Single Victory,’ Writes Author of Buoyant New Book on Activism

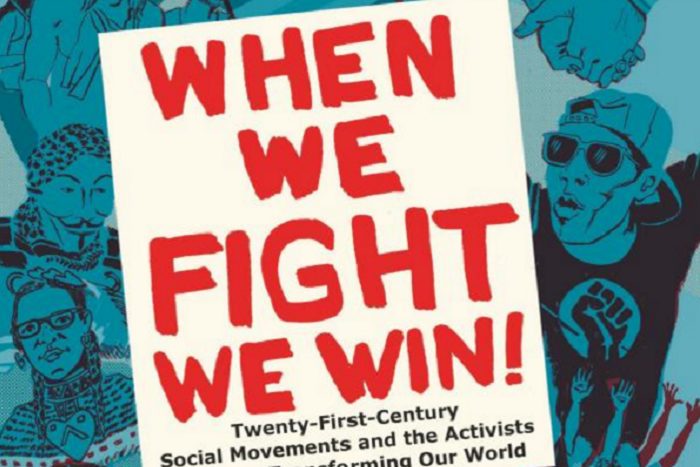

An inspiring—if perhaps overly optimistic—book, When We Fight We Win!: Twenty-First-Century Social Movements and the Activists That Are Transforming Our World, showcases six areas in which progressive shifts have already happened or are possible thanks to long-range activism and political vision.

On any given day, all it takes is a quick look at the headlines to see the sorry state of world politics: Hunger, poverty, war, environmental degradation, campus shootings and stabbings, child abuse and neglect, and police brutality are just some of the atrocities that make the future seem bleak, if not hopeless.

But not everyone is filled with despair.

For one, Schott Foundation for Public Education Board Co-Chair Greg Jobin-Leeds, himself a seasoned Cambridge, Massachusetts-based community organizer, sees numerous possibilities in today’s political morass. Indeed, his inspiring—if perhaps overly optimistic—new book, When We Fight We Win!: Twenty-First-Century Social Movements and the Activists That Are Transforming Our World, showcases six areas in which he believes progressive shifts have already happened or are possible thanks to long-range activism and political vision. These include campaigns for LGBTQ equality; efforts to preserve and defend public education; challenges to mass incarceration and prison privatization; immigrant rights; and the promotion of economic and environmental justice. Each section includes interviews and case studies, as well as illustrations by members of AgitArte, an activist art collective with chapters in Puerto Rico and Massachusetts, underscoring the role of visual culture in popularizing activism.

“I asked leaders of … thriving social movements, ‘What are the lessons you’ve learned that you would like to pass on to new activists?'” Jobin-Leeds writes in an introduction to the text. Eager to parse organizing strategies and better understand the incremental steps that lead to bigger, bolder victories, Jobin-Leeds interrogates what successful campaigners have done to increase the likelihood of victory, and questions how they remain upbeat despite working in a less-than-progressive political milieu. He was not looking for conformity, he writes: Instead, he was eager to capture a range of organizing experiences.

In the book’s foreword, for example, Rinku Sen, publisher of Colorlines and president and executive director of Race Forward: The Center for Racial Justice Innovation, takes a measured approach when compared with Jobin-Leeds’ buoyant point of view. She notes the enormity of challenging the status quo, writing, “Whether or not we win will be based on many things other than our own strategy and strength. Even strong, huge movements sometimes fail.” She continues, “There is, however, no path to victory without trying.”

Tapping into the desire to push back rather than fold in the face of obstacles is at the heart of When We Fight We Win! and Jobin-Leeds spent years interviewing activists to try and determine why they feel compelled to do this work. He also wanted to better understand how movements can create real and enduring change; tease out strategies that are consistently successful; and find effective tools to deflect apathy. These in-depth interviews supplement Jobin-Leeds’ more general points and give a hands-on immediacy to the stories and research he presents.

His introduction sets the stage and posits the benefits gleaned from organizing:

When we fight—building an organization, joining a community of activists—we win not only communal victories but also our own personal transformation, enabling us to discover common root causes to problems that had seemed unconnected before. Understanding root causes can ally us with others—across issues, cultures, identities. This aggregates individual fights into broad movement struggles, and by working in solidarity together we can realize far-reaching, systemic change. Winning lies not in a single victory, but in many victories and the lifelong struggle to change injustice and create a future based on a bold, transformative vision.

This philosophy, of course, requires us to celebrate incremental wins, no matter how small. It also requires us to acknowledge the enormous rush that comes from disrupting business-as-usual and its powerful enforcers. After all, if fighting back is joyless, why do it?

Case in point: the movement for LGBTQ equality.

Jobin-Leeds reminds us that five decades ago, sodomy was a crime in every U.S. state and the idea of marriage equality was a pipe dream writ large. So what happened? In a word, he says, AIDS: an unanticipated health crisis and mass tragedy that gave the LGBTQ community new prominence in the public eye. Rea Carey, executive director of the National LGBTQ Task Force, tells Jobin-Leeds that when people started becoming ill, “There were a lot of men—including men in urban areas who had some level of class or race privilege—who were being denied access to their partners as they were dying in hospitals because they weren’t ‘family.’” Their stories of emotional trauma were heartbreaking and led, years later, to a demand that their relationships be recognized and validated.

Evan Wolfson, founder and president of Freedom to Marry, agrees with Carey, adding, “AIDS broke the silence about gay people’s lives and really prompted non-gay people to think about gay people in a different way. It prompted gay people to embrace this language of inclusion, most preeminently marriage. That, in turn, accelerated our inclusion in society and the change in attitudes.”

AIDS’ public accounting of love and loss presaged a dramatic shift in assumptions and ideas about what it meant to be queer. It also went hand-in-hand with thrillingly defiant public actions in streets, pharmaceutical company boardrooms, and government offices throughout the country.

Of course, homophobia has not been eradicated; nor has AIDS stigma. But as a result of ACT UP and other queer-led organizations, access to life-changing drugs increased. In addition, as family and friends pushed their way into hospital rooms, the broadening of the definition of “kin” took root: Jobin-Leeds and his activist contacts theorize that this is part of what eventually led to marriage equality. All of this is surely worth celebrating; at the same time, progressives understand that the right to wed is but one demand on a long roster of LGBTQ needs.

As Carey explains, “We can’t ask someone to be an undocumented immigrant one day, a lesbian the next, and a mom on the third day … Our vision is about … transforming society so that she can be all of those things every single day and that there would be a connectedness among social justice workers and among the organizations and agendas, if you will, to make her life whole.”

These linkages, Carey said, have led the Task Force to work on a range of issues, including criminal justice reform, liberalized immigration, public education, and economic justice—issues that, she says, the largely white male activists who founded the Task Force initially considered tangential to LGBTQ rights.

Still, both Carey and others stress that not every campaign will result in victory. Paulina Helm-Hernández of Southerners on New Ground (SONG) tells Jobin-Leeds about a 2012 campaign against a same-sex marriage ban in North Carolina, a battle she says the activists anticipated losing. Nonetheless, SONG committed itself to reaching one million people to discuss “the future of our state, and about the divisive tactics of the Right, and about the reality of how integrated LGBT communities in North Carolina actually are to immigrant communities, to other communities of color—it really just became a huge opportunity for us, and I would say a success in terms of helping not just amplify the grassroots organizing that makes moments like that possible, but to say it does matter.” In essence, despite losing the war, they won what they hope will be lasting personal connections with local residents.

What’s more, Helm-Hernández emphasizes another secondary gain: When other folks saw that it was possible for individuals and organizations to stand up and speak out, it empowered them to do likewise.

Among today’s most motivated activists, Jobin-Leeds writes, are the DREAMers, young immigrant women and men whose efforts have led many people to think differently about immigration policy. Although Jobin-Leeds concedes that the United States has still not enacted meaningful reform, he reports that hundreds of immigrant youth have bravely declared themselves not only undocumented, but unafraid. They’ve told their stories, and those of their parents and grandparents, to audiences throughout the country—as well as before Congress—and their efforts have begun to pay off. The New York Times, for one, has stopped using the term “illegal” to describe undocumented people, and several states now allow undocumented residents to pay in-state tuition rates, a change that has allowed many to enroll in two- and four-year degree programs.

“DREAMers from across the country have profoundly changed the national discourse and influenced organizing tactics around immigration—catapulting an issue forward,” Jobin-Leeds reports. “Storytelling combined with direct action transforms people into activists.”

And although obtaining citizenship for the approximately 11 million undocumented U.S residents is proving difficult in today’s political climate, Jobin-Leeds writes that it remains a long-term goal.

Like the DREAMers, activists working on other issues also sometimes set their sights on local gains—targeting a recalcitrant landlord or a bank that is threatening foreclosure, for example—rather than attempting to change national policy, and Jobin-Leeds chronicles the successful efforts of the Boston-based City Life/Vida Urbana to create eviction-free zones in low-income areas. Similarly, the Restaurant Opportunities Centers United have driven companies like the Fireman Hospitality Group to settle claims for back wages and tips, and develop policies to curtail sexual harassment and discrimination. Equally significant, environmental groups such as 350.org have pushed colleges and philanthropies to divest from the fossil fuel industry.

Drops in the bucket? Maybe. But as the organizers in When We Fight We Win! repeatedly remind readers, small changes often lead to bigger ones. Furthermore, organizing requires us to take a long view of history to forestall becoming demoralized. After all, given today’s Republican assault on reproductive justice; the overt expressions of racism and xenophobia by political office holders, presidential candidates, and everyday individuals; the non-stop push to privatize once-public services; and our seemingly endless involvement in numerous wars, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed, angry, and powerless.

When We Fight We Win! admits this, albeit indirectly, and recognizes that there are no guaranteed victories. Nonetheless, the book enthusiastically celebrates activism as personally and politically invigorating. Indeed, when all is said and done, we have two choices: We can either accept the current state of affairs or try to foment change. If we opt for the latter, we may not win everything we dream of, but at least we’ll know we tried. Isn’t that better than languishing in grief and anger?