Sentenced to Abuse: Trans People in Prison Suffer Rape, Coercion, Denial of Medical Treatment

Trans prisoners continue to be housed in facilities with the opposite gender, resulting in discrimination, trauma, and rape.

Read other pieces in Rewire’s Women, Incarcerated series here.

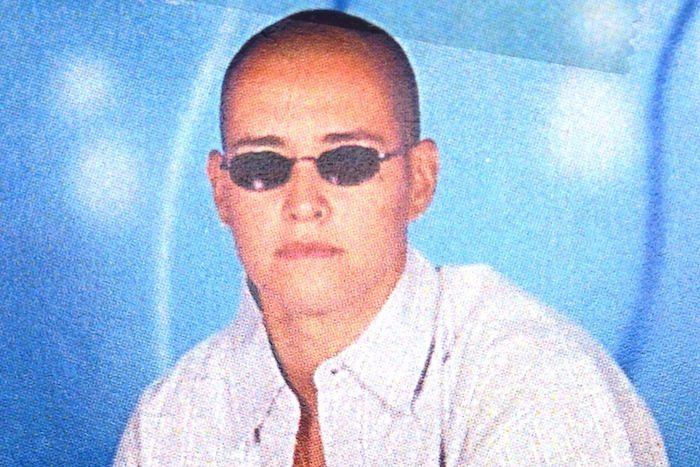

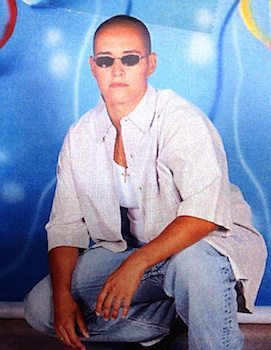

In 2009, Janetta Johnson was sentenced to 71 months for possession and intent to distribute methamphetamine. When the economy plummeted in 2008, Johnson says she panicked and, like many women offenders, began selling drugs as a way to survive.

What makes Johnson’s case stand out, however, is that she is a trans woman. Designated as male at birth, Johnson has identified and lived as a woman since she was a child.

Nonetheless at her sentencing, the judge presiding over her case sent her to Sheridan federal correctional institution, a facility 50 miles southwest of Portland, Oregon that houses more than 1200 male inmates.

“When I was first sentenced to the men’s facility, I told the judge, ‘You know you’re sentencing me to sexual abuse too,” Johnson told Rewire. “It’s highly likely that a transgender woman in a men’s facility will be sexually assaulted. There’s no ifs, ands, or buts about it.”

Johnson’s prediction turned out to be correct. At Sheridan, she says she experienced sustained sexual assault, including resorting to oral sex to avoid penetrative rape. She also endured harassment from guards, and inadequate medical treatment for her gender dysphoria. The officials charged with her protection often made things worse.

“When we as transgender people make a request for safety, they feel like we’re asking for extra privilege,” Johnson told Rewire.

Johnson was released from custody in April 2013. She is now the program director for the Transgender, Gender Variant, and Intersex Justice Project, an activist organization made up of low-income transgender women of color and their families, who are in prison, formerly incarcerated, or targeted by the police. She is focused specifically on re-entry services for trans women of color leaving prison.

Johnson’s experience of sexual violence in prison is not unique among trans individuals, who, because of continued social stigma and exclusion, are overrepresented among the nation’s incarcerated population.

Discriminated against for housing and employment, trans people face homelessness and poverty at exceptionally high rates. In a 2000 survey of 252 gender variant residents of Washington, D.C., 29 percent of respondents reported no source of income. Another 31 percent reported annual incomes under $10,000. Poverty and lack of opportunity lead to crimes of survival, like sex work, drug sales, and theft, according to a 2007 report by the Sylvia Rivera Law Project.

Despite these realities, correctional systems have so far failed to meet the needs of the trans people, who continue to suffer severe sexual assault, as well as psychological harm from consistent denial of medically necessary hormone treatment, gender-appropriate clothing and personal hygiene products. And, like Johnson, trans individuals are almost always mis-housed in facilities intended for people of the opposite gender.

“Overall, prisons are incredibly gendered spaces,” Jennifer Orthwein at the Transgender Law Center told Rewire. “Right now trans prisoners are at extreme risk for a whole host of damaging and traumatic consequences.”

Rewire’s Women, Incarcerated series documents systemic abuses in prisons and jails that affect women, whose numbers behind bars continue to grow. The experience of trans people further underscores the brutally gendered nature of incarceration.

“I Had to Negotiate”

The word trans encompasses a whole range of identities on the gender spectrum, including people who are transgender, transsexual, genderqueer, and gender nonconforming. Trans is a term for someone who is not a cisgender woman or man.

In the past year, there has been a slow but steady increase in mainstream knowledge and understanding of trans people and the issues they confront.

Popular television shows feature trans characters, and most recently, former Olympian and reality TV star Bruce Jenner publicly announced that he is in transition, becoming a woman. The White House has taken steps to expand legal protections to transgender people.

But trans advocates told Rewire that pop culture can paint a misleadingly rosy picture of life for many trans men and women. Experts were quick to point out that if Laverne Cox’s character in Orange Is the New Black went to prison in real life, she would almost certainly be sent to a men’s facility, where being the sole woman among hundreds of men would jeopardize her physical and mental safety.

It’s difficult to determine how many trans individuals are currently in prisons or jails. The Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates that there were 3,209 transgender prisoners in state and federal facilities in 2011-2012, or about 0.22 percent of the national prison population, according to National Center for Transgender Equality calculations. The justice bureau estimated there were 1,709 transgender inmates in local jails, or about 0.23 percent of the national jail population.

But trans experts say these numbers are likely a gross underestimate. Most corrections facilities don’t keep track of people who identify as trans, and the justice bureau’s data are based on the narrow questions on the National Inmate Survey, which only offers prisoners three options for their gender identity: male, female, or transgender. When the question is asked this way, a large number of transgender people may simply check off “male” or “female,” according to the National Center for Transgender Equality.

The danger of identifying as transgender in prison could also skew the numbers, according to the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, an organization that provides free legal aid to low-income transgender, gender non-conforming, and intersex people of color. Attorneys and advocates at the project say that often prisoners will write two or three letters to them before actually identifying as trans, because of the stigma and vulnerability of that identity in prison, as well on the outside.

In 2011, the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force surveyed 6,450 transgender and gender non-conforming people across the country. Sixteen percent of respondents reported they had been incarcerated at some point in their lives. The risk of incarceration was more pronounced for people of color: 47 percent of Black respondents and 30 percent of American Indian respondents reported they had been incarcerated.

In the past few months, trans prisoners and activists have cautiously celebrated two legal developments that signal progress in the treatment of incarcerated transgender people: Georgia agreed to provide hormone therapy for transgender inmates in state prisons, and a federal judge in California ordered that the California Department of Corrections grant a transgender inmate access to gender-affirming surgery.

But in most jurisdictions, conditions remain deplorable, in part because the vast majority of trans people are housed with inmates of the opposite gender.

At Sheridan, Janetta Johnson says she was the only out trans woman on the compound. Her physical appearance prevented her from being able to pass as a man, even if she had wanted to. With long, black hair, carefully made-up features, and an array of necklaces and earrings, today she looks like any other woman on the streets of San Francisco.

“There was no real way I couldn’t be ‘out,” Johnson says. “I have 38 DDs.”

There were a few other inmates who Johnson suspected were trans women, but she says they would not associate with her because they feared for their physical safety. They claimed to have wives and children back home, and they would not speak or make eye contact with Johnson.

Tangela Bivens, Johnson’s sister, was one of Johnson’s main advocates during her incarceration.

“I just feel like they didn’t protect her enough. She used to say that people would threaten her,” Bivens told Rewire. Bivens says she called Sheridan to say that her sister was being threatened, but the situation on the ground didn’t change.

“I would cry and cry,” Bivens said. “I used to work overtime just to make sure that I could send her money, so that if something happened, her excuse wouldn’t be, ‘I didn’t have enough money to call.’”

A National Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) audit, published in April 2014—two years after Johnson’s release—paints a different picture of conditions for trans prisoners at Sheridan than what Johnson says she experienced. The report said there were four transgender people housed at Sheridan, and the facility met all federal PREA standards, including screening prisoners who might be at risk for victimization and abuse, and training staff on how to conduct pat downs on cross-gender and transgender people. No grievances had been filed regarding sexual abuse at Sheridan, according to the report.

It is difficult to determine whether conditions had simply changed since Johnson’s time at the facility. Sheridan did not answer Rewire’s questions about Johnson’s allegations of sustained abuse, or the facility’s current treatment of trans prisoners.

Johnson describes Sheridan as a place of relentless, life-or-death negotiations for safety, with sex as one of the only bargaining chips. Constantly at risk of being raped, she endured some sexual acts in exchange for protection.

“The best way I can describe it is, I was being raped, and I had to negotiate,” Johnson said.

Many trans women in prison submit to coercive sex—a form of sexual violence—for protection or access to hormones, according to National Prison Rape Elimination Commission testimony. A UC Irvine study found that sexual assault is 13 times more prevalent among transgender inmates than the general prison population, with 59 percent of transgender prisoners reporting being sexually assaulted while in a California correctional facility.

Often, Johnson says, she would wake up to find her cellmate touching her breasts and fondling her. She went to report the assault to a guard, but before she could finish, the guard urged her to stop, according to Johnson. The only place he could house her for protection was in the Security Housing Unit (SHU), a solitary confinement cell where she would be locked in for 23 hours a day. In addition to the isolation, the SHU would make Johnson ineligible for the prison’s residential drug treatment program, and the 18-month-early release that went with it. To stay out of the SHU, Johnson realized she had to face the sexual violence by herself.

Claire Leary, Johnson’s court-appointed lawyer, represented Johnson from 2009 to August 2010, and received troubling letters and phone calls from Johnson while she was at Sheridan.

“I just remember it was a horrible bind,” Leary told Rewire, of Johnson’s time at Sheridan. “You can’t get the access to services or treatments you need, without being in danger.”

A Matter of Life and Death

In early April of this year, the Justice Department backed a case filed by Ashley Diamond, a trans woman serving time at a maximum-security men’s prison in Georgia. Diamond’s lawsuit details the nightmarish conditions of her incarceration: placement in solitary confinement for “pretending to be a woman,” brutal assaults by fellow inmates, and complete disregard from staff about her safety.

But perhaps most traumatic of all, the lawsuit describes how Diamond was denied the hormones she had taken for 17 years before her incarceration. Without the necessary medication, Diamond “violently transformed,” losing breast tissue and experiencing muscle spasms, according to the lawsuit. Diamond’s lawyer, Chinyere Ezie, said Diamond has attempted to castrate herself so she can go back to being the woman she knows she is.

Since childhood, multiple medical providers had diagnosed Diamond with gender dysphoria, a medical condition in which one’s gender identity differs from the gender assigned at birth, causing clinically significant distress. If gender dysphoria is untreated, it can lead to suicidal ideation, and the impulse to self-castrate and self-harm. People with gender dysphoria are often called transsexual or transgender.

There has long been debate about how to treat people with gender dysphoria. In some areas, draconian policies have given way to more humane ones.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) used to have a “freeze-frame” policy for people who had gender dysphoria, which froze treatment at the level it was when a person was incarcerated. If, for example, a trans woman was not taking any hormones before she was incarcerated, she would be unable to access hormones during her incarceration, even if prison doctors diagnosed her with gender dysphoria while she was behind bars.

In 2011, BOP changed their policy in response to a lawsuit, and released a memo stating, “Treatment options [for people with gender dysphoria] will not be precluded solely due to level of services received, or lack of services, prior to incarceration.”

The National Commission on Correctional Healthcare (NCCHC), which accredits prison health-care programs, has written that freeze frame policies are “inappropriate and out of step with medical standards.” In court filings earlier this month, the Department of Justice wrote that freeze frame policies are unconstitutional, and violate the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment.

Despite medical and legal consensus, trans people in prisons and jails often cannot access the hormones they need.

In the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force survey of 6,450 trans people across the country, 17 percent of people who had been incarcerated reported denial of hormones while in prison. Black and low-income respondents reported even higher rates of denial.

In general, prison healthcare is notoriously bad. Prisoners have sued for being denied prenatal treatment, medically indicated methadone, cancer treatment and mental health services. Even given this backdrop, the authors of the 2007 Sylvia Rivera Law Project report claim that within a context of neglectful and inadequate medical care, trans people in prison receive “additional forms of care-related discrimination and neglect.”

A week after the Justice Department signed on to Diamond’s case, the Georgia Department of Corrections agreed to provide Diamond with hormones. But the dose is still too low to be therapeutic, according to Diamond’s lawyers.

Last week, the federal Department of Corrections transferred Diamond back to a medium-security facility in Georgia after an inmate at the maximum-security prison touched her face, and after Diamond received a sexually threatening note from another inmate, according to news reports. Her lawsuit says that the only time during her incarceration that she has not been subject to sexual abuse was when she was at the same medium-security facility. However, it is unclear whether the transfer will have any effect on her access to hormone therapy.

Diamond is not the only transgender prisoner who has sued for hormones in prison.

Keirra Lacey James is a trans woman currently incarcerated at the Pontiac Correctional Center, a maximum-security prison for men in Illinois. In a handwritten complaint filed in 2012, James detailed how she was denied hormone treatment for her gender dysphoria, even though she had lived as a woman since the age of 16 and had been diagnosed with gender dysphoria by a prison psychiatrist.

When she asked for hormone treatment, the medical director of the prison told James, “We don’t give out hormones. You didn’t get them when you were free, and you won’t now. Deal with it.”

In neat, looping script, James wrote that she had attempted to mutilate her arms, legs, and genitals, and had been on suicide watch multiple times since being denied treatment.

The Illinois Department of Corrections settled with James in October 2014, and denied liability, according to Nicole Wilson, a spokeswoman for IDOC. In an email to Rewire, Wilson said the department could not comment on any specific treatment currently provided to an inmate. She added that the IDOC has not enacted any new policies regarding hormone treatment since the lawsuit.

Joey Mogul, a lawyer for James, says that part of the settlement stipulates that if any changes are made to James’ hormone treatment, the Illinois Department of Corrections must tell James’ lawyers.

“[Keira] courageously sought the treatment on her own,” Mogul told Rewire. “I’m hoping that the tide is turning. All prison and detention institutions have a duty to provide this necessary medical treatment.”

Ezie, Diamond’s lawyer, emphasizes that for transgender inmates like Diamond and James, hormone therapy is not cosmetic.

“It’s not about playing dress up. It’s a matter of life and death,” Ezie told Rewire. “It’s about feeling like you’re living in the right body, and like you have a compelling reason to live.”

Forced Feminization

In addition to high rates of sexual assault and lack of medical care, trans prisoners also describe a general atmosphere of hostility aimed at people who do not express the “correct” gender while incarcerated.

Cookie Concepcion is a trans male activist who has been incarcerated at the Central California Women’s Facility since 1998. In a phone interview with Rewire, Concepcion described a system of “forced feminization,” in which he and other gender non-conforming inmates are disciplined for not obeying rigid gender rules.

The rules can seem bizarre. Concepcion says inmates had to fight to be allowed to purchase products “made for men”—like Axe body wash, or Irish Spring soap—because they live in a women’s prison.

A spokeswoman for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation said, “Our policies allow for transgender inmates to purchase items that particular gender would use.” She added that she did not know whether someone who wasn’t diagnosed as transgender could purchase those products.

“What was a scent going to do to somebody?” Concepcion asked. “If a bar of soap says ‘men’ on it, how does that affect the rehabilitation of someone in this institution?”

The prison’s policies target even minute details that people on the outside often take for granted. If a prisoner is not officially diagnosed with gender dysphoria, that prisoner cannot wear boxers, and must wear women’s underwear. (California’s policy on the treatment of transgender prisoners is available here.)

Concepcion says this policy makes no sense, considering the number of inmates who are lesbian, bisexual, or gender non-conforming, but who do not identify as transgender.

“Anybody can walk into any store, lawfully, and they can purchase any type of undergarment they want, and wear it,” Concepcion says. “I want to know what it is about prison that has to regulate that? What is the safety and security issue?”

Sasha Alexander at the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, says this type of policy is understandable within a system meant to impose control at all levels.

“They’re doing this to break people down and discourage people from having gender self-determination,” Alexander told Rewire. “On the outside, this happens as well, but [prison officials] are even more able to enforce those binary ideas of sex and gender.”

Concepcion believes that no matter what he does, he will never fit the image of a rehabilitated female prisoner that the officials at CCWF are looking for. Originally arrested for gang-related murder, Concepcion says he has changed dramatically. He has participated in an at-risk youth intervention program and multiple self-help groups behind bars. He works as a clerk, providing recreational therapy for developmentally disabled people. He also serves on the board of directors of Justice Now, a human rights organization that provides free legal services to people incarcerated in California women’s prisons.

Even so, Concepcion says administrators see his masculinity as a sign that he is still a criminal.

“Really what’s sad about it is the fact that I am so freely able to claim [my gender identity] shows such a growth in my self-esteem. They have it so backwards,” Concepcion says.

When asked whether masculinity could be seen as a sign that a female inmate has not rehabilitated, the spokeswoman for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation told Rewire, “I’ve never heard anyone say that, and I’ve never known anyone to believe that.”

In terms of how to make prisons safer spaces for trans people, activists and currently and formerly incarcerated people were quick to say that the fundamental problem is the disproportionate policing and incarceration of people in the trans community.

Even so, there are some obvious ways to reform the system, according to Alexander of the Sylvia Rivera Law Project. Department of Corrections staff should be trained so they know what it means to be transgender, and what specific safety and health concerns the transgender community may have. Transgender and gender non-conforming administrators and health-care providers should be hired, and trans-specific programs and self-help groups should be available to incarcerated people. Prison health care (which is often inadequate) should include “safe, affirming access to hormones,” and people should not be housed based on their genitalia, but instead where they feel most safe. Finally, prisons should not use solitary confinement as the primary means of protecting trans people behind bars.

But activists say that to truly change the trans community’s relationship with incarceration, they must tackle the underlying problems of poverty, homelessness, and discrimination on the outside.

As Colby Lenz, a volunteer for the California Coalition for Women Prisoners, told Rewire, “What we don’t need is a better cage. What we need is more support and services and resources for people, before they get trapped in prison.”

Editor’s note: In some cases, the individuals in this story have chosen new names that reflect their gender identity. Rewire has reviewed public records to reference legal names in each of these cases. Rewire uses the names preferred by these individuals. Also, this article uses the word trans to refer to transgender, transsexual, genderqueer, and gender nonconforming individuals. A prior version used the term trans*, but we have clarified the terminology in this piece to reflect the current language used in the LGBTQ community.