After Hobby Lobby, Democratic Legislators Push Anew for Equal Rights Amendment

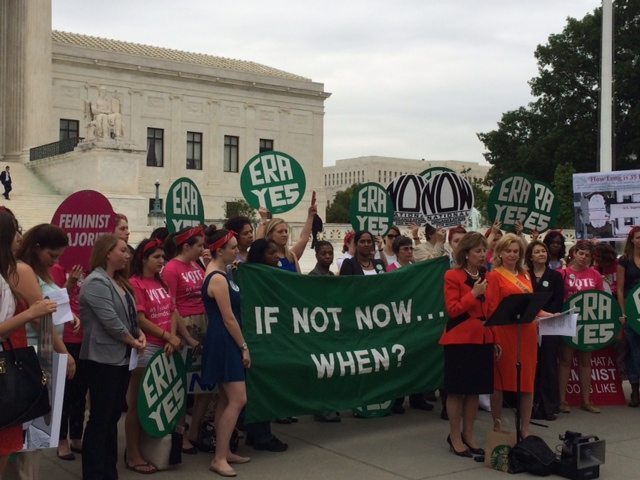

Democratic legislators and women's rights advocates called out the Supreme Court as they rallied to pass an amendment to the U.S. Constitution guaranteeing equal rights to women.

Leah Meredith had worked hard at Geico for four years and gotten several promotions, and she was up for another promotion when she got pregnant. It was a difficult pregnancy, she said, and although by the third trimester she could barely walk, she still kept up her work. But when she was called into a meeting right before she took maternity leave, she was advised that she would not be receiving her promotion. She filed a pregnancy discrimination complaint with human resources, and they said they would investigate.

After she came back from the four months of leave she needed to heal and bond with her daughter, Meredith said, “[the] response was that there was no response. They weren’t sure what my position would be. I had no desk, and my items were packed in broken boxes.”

Pregnancy discrimination on the job is common to this day, despite laws intended to prevent it, and that’s just one of many reasons to ratify an Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the U.S. Constitution, said Democratic legislators and women’s rights advocates at a Thursday morning rally in front of the Supreme Court.

“The Supreme Court has made clear that women are not necessarily considered equal in the Constitution,” said Rep. Jackie Speier (D-CA) at the rally. Speier has introduced a resolution in the House that would make it easier to ratify the ERA.

Choosing the Supreme Court as a protest location rather than, say, Congress, sent the message that the 14th Amendment isn’t always enough to uphold women’s equality in the highest court of the land. A sitting Supreme Court justice, Antonin Scalia, has said outright that the Constitution does not explicitly protect women: “Certainly the Constitution does not require discrimination on the basis of sex. The only issue is whether it prohibits it. It doesn’t.”

The Hobby Lobby decision was fresh in the mind of many speakers, who said it enables sex discrimination because religious employers can effectively force women to pay more for medical care. The Affordable Care Act marks the first time that insurers are not allowed to “charge [a woman] more and give her less,” said Feminist Majority Foundation president Eleanor Smeal, noting that before the ACA passed, women were discriminated against by because they were charged 50 percent more than men and because 80 percent of individual policies did not cover maternity care.

Speakers pointed to the Court’s 100-foot buffer zone as an example of both hypocrisy and unfairness to women, given the recent McCullen v. Coakley decision striking down a 35-foot buffer zone that protected women from protesters at reproductive health clinics. And the 2000 U.S. v. Morrison case, which struck down part of the Violence Against Women Act, was held up as an example of why women need stronger constitutional protections when local courts or schools fail to adequately address sexual violence.

With an ERA, Speier said, women would no longer have to prove not only that an offense occurred, but that it was an intentional act of discrimination. “No longer would legal arguments for women be doubly burdened,” she said.

The ERA was introduced in Congress every session from 1923 to 1972, when it was finally passed. Thirty-five states ratified it, three short of the threshold needed to be included in the Constitution, but conservative campaigns against the ERA stalled its momentum. It failed to reach 38 states before the 1979 deadline that Congress had imposed when the amendment was introduced, and failed again before 1982 when the deadline was extended.

The amendment has been reintroduced every year since 1982, as it has this year in the House by Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D-CA). But a newer strategy, called the “three-state strategy,” has been to try to get Congress to repeal the time restriction on ratifying the amendment. If passed, HJR 113 and SJR 15 would count the ratification votes passed in 35 states between 1972 and 1977, and only three more states would need to get on board for the amendment to be ratified. Illinois is scheduled to vote on the ERA in November, potentially making it state number 36.

A 2012 poll found that 91 percent of Americans supported a Constitutional guarantee of equal rights for men and women. In fact, said Feminist Majority Foundation president Eleanor Smeal, “Most people think we already have one!”

Advocates and legislators said they intend to make the ERA a campaign issue. “We could easily pass it next year if the women and like minded men in this upcoming election would make it a fundamental principle that they will not vote for any candidate who does not say and believe that equal means equal, not in rhetoric, but in the Constitution of the United States, for women and men,” Maloney said.

Attendees of the rally dressed as Rosie the Riveter, echoing another protest this year urging President Obama to pass a federal “Good Jobs” policy. The army of Rosies who took over men’s jobs when they went to war, speakers said, were paid the same wage as the men they replaced—but even that much is sometimes a challenge today.

“We have had to fight, and fight, and lose, and fight, and lose, and get up and fight again, and win, and have it cut back, and fight again, and do it over and over and over and over again,” said Terry O’Neill, president of the National Organization for Women, at the rally. “If we had an Equal Rights Amendment, we wouldn’t have to be spending all of our resources, and all of our energy, and all of our attention, just getting to a little bit more of equality.”