No Longer a Front-Page Story, ‘Beatriz’ Continues to Struggle From Denial of Abortion Care

The story of “Beatriz,” the 22-year-old woman caught in the firestorm of the abortion conflict in El Salvador, no longer appears on the front pages of the country’s newspapers nor on TV nightly news. Beatriz, however, continues to struggle daily.

The story of “Beatriz,” the 22-year-old woman caught in the firestorm of the abortion conflict in El Salvador, no longer appears on the front pages of the country’s newspapers nor on TV nightly news. Beatriz, however, struggles daily with poor health resulting from denial of abortion care, while trying to build a life for herself and her 20-month-old son.

Beatriz’s story garnered international coverage in April when she was denied an abortion by the government of El Salvador, even though her fetus was not viable and her doctors had determined continuing the pregnancy was putting her life in grave danger. In El Salvador, abortion is illegal even when the mother’s life is in danger, a policy supported by both the current government, the powerful Catholic bishops of El Salvador, and equally powerful anti-choice groups allied with ultra-conservative Catholic theology. Despite the law, in early April 2013 doctors advised Beatriz of the dire consequences of continuing her pregnancy, and she requested an abortion. Under Salvadoran law, a woman who has an abortion and anyone who assists in providing one both face prison terms of up to 50 years. Still, Beatriz persevered in pressing her case.

With the support of the Salvadoran organization, Agrupación Ciudadana por la Despenalización del Aborto Terapéutico, Ético y Eugenésico (Citizen Group for the Decriminalization of Therapeutic, Ethical or Eugenic Abortion), Beatriz appealed to the Salvadoran Supreme Court. The court delayed its response for several weeks—during which time Beatriz’s health continued to decline—and then refused to take any effective action. Finally, the InterAmerican Human Rights Court, to which Beatriz had also appealed, ordered the Salvadoran government to act, and her doctors performed the abortion. Though her life was saved in the short term, Beatriz’s health was severely impaired by weeks of needless suffering and the denial of swift treatment at an earlier stage in her pregnancy. Moreover, anti-choice groups and even the judges from the Salvadoran Supreme Court continued to argue that Beatriz was never in any real danger and was being manipulated by feminist groups.

Compounding the emotional stress during her hospitalization, anti-choice groups managed to contact Beatriz by phone to attempt to convince her to change her mind about requesting an abortion. They offered to move her from the under-funded and overcrowded public maternity hospital to an exclusive private hospital, which they described as equivalent to a five–star hotel, and to take care of all her expenses. However, Beatriz chose to stay in the public hospital and continue her alliance with the Agrupación. In an on-the-ground interview with Rewire in El Salvador, Morena Herrera, president of the Agrupación, said “the most disgusting and inhumane” episode occurred when the anti-choice group brought Beatriz a basket of baby clothes, including small knitted caps to cover the head of the anencephalic fetus she was carrying.

Beatriz’s fight to save her own life provided the citizens of El Salvador a real-time view of the actual meaning and costs of a law about which a large share of the population previously had little awareness.

Three months after the abortion, Beatriz is holding her own for the moment. However, her future, both short- and long-term, remains quite uncertain because of permanent health problems, including aggravated lupus and kidney disease. She is home with her family, most importantly with her son, as she figures out options for medical treatments, employment possibilities, the needs of her son, and her living situation. The torture and humiliation of fighting for a medically indicated abortion, the stress of her illnesses, and the pain of the brief life and inevitable death of the anencephalic baby she had wanted seriously compromised her already fragile health.

The Agrupación, the Colectiva Feminista and other feminist groups maintain close contact with Beatriz and provide regular support. Morena Herrera explained in a phone interview with Rewire that the organization is talking with the Ministry of Health to ensure that the government complies with the follow-up treatment Beatriz was assured she would receive. Her lupus symptoms are worsening and the condition of her kidneys still has not been determined. Even with medication, she suffers constant pain. The Agrupación is working to get her to get more in-depth, comprehensive medical tests in order to have a clear diagnosis and treatment plan. They have also helped her obtain psychological counseling.

But, these efforts cannot reverse the damage done by to her body and her health by a pregnancy that should have been terminated much earlier.

In a conversation with Rewire on the ground in El Salvador, Beatriz recalled the two months she spent in the hospital awaiting the procedure she requested to save her life:

The time in the hospital was really difficult, and I suffered a lot. From the pregnancy the lupus gave me spots and rashes all over my body as if it were burned. I never slept well. I was stressed the whole time. All I could think about was my son without me. I just wanted to be with him.

During her hospital stay the Salvadoran Supreme Court summoned her to testify about her request for an abortion. “I’m not sure that they believed me. The Institute of Legal Medicine said nothing serious was going to happen to me. I felt really bad when they said that. Only I know how I feel in my body, not them.”

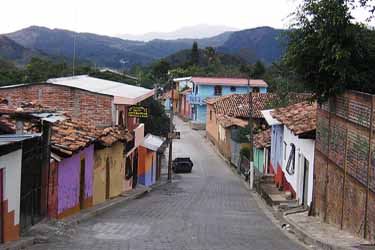

Beatriz currently lives with family members in an isolated rural area of the country located about a three-hour drive from San Salvador. A section of that journey is over barely passable unpaved roads. The region provides almost no opportunities for employment. She attempts to generate at least a minimal income through a small store she set up on shelves in the front of her house where she sells a few basic goods to her neighbors. Feminist groups helped her with business skills and continue to provide her with a small amount of funding, business advice and moral support. In addition, she devotes much of her attention to her 20-month old son who had a difficult premature birth and then a lengthy separation from his mother. He requires medical attention to address developmental delays in walking and talking. She would like to study cosmetology, but poor health and the need for frequent medical appointments for herself and her son prevent her from doing so. Appointments are complicated to schedule because of the long distances and the limited bus transportation to the city. She is also considering moving to another rural community where other family members live.

As a woman who is young, poor, and rural, Beatriz fits the profile of women negatively affected by the country’s draconian abortion laws. At a huge cost to her physical and emotional health, and almost her life, she fought to have the life-saving abortion she requested and deserved.

How does she see the Salvadoran law that could have killed her? “I don’t think they should let happen to any other woman what happened to me. When a woman is extremely sick and is pregnant, they should interrupt the pregnancy, so that nothing bad happens like what happened to me.”

Her struggle to save her life placed the question of the abortion squarely on the public agenda in El Salvador. Abortion has been transformed from a word that was almost never spoken aloud to a subject of intense public concern and discussion. This dramatic change has energized feminists, youth groups, university students, human rights organizers, and inclusive religious groups who want to keep the momentum alive. The Agrupación continues its ongoing commitment to organizing legal cases to secure the release of women imprisoned with abortion-related convictions, as well as its long-term goal of legislative change to decriminalize abortion. But the road ahead remains steep, arduous, and uncertain, like the one Beatriz continues to climb.