Gay Is Not the New Black: The Supreme Court and the Politics of Misrecognition

LGBTQ rights are not the single civil rights issue of our time. To think otherwise, as all too many do, is the same sort of misrecognition that shaped the Supreme Court’s VRA ruling: the notion that the work of the civil rights movement is done, and it’s time for LGBTQ people to take up their mantle.

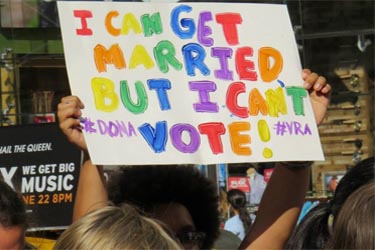

Like many queer people of color, my celebration of the Supreme Court’s recent rulings on the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) and Proposition 8 has been tempered with concern over the Court’s mixed ruling on affirmative action and rage over its gutting of voting rights and Native sovereignty. It’s particularly infuriating that the difference between DOMA being struck down and a key section of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) being stripped of its effectiveness ultimately came down to a single powerful, white, straight man: perennial swing vote Justice Anthony Kennedy.

The Politics of Misrecognition

What makes Justice Kennedy able to see the need for equal protections for same-sex couples when he apparently doesn’t for robust measures protecting the voting rights of Black and other marginalized citizens? There’s an important lesson here for liberals and progressives in this seeming paradox. Both decisions are examples of what political scientist and MSNBC host Melissa Harris-Perry describes in her book Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America as a “politics of recognition” and “misrecognition.”

If, as Hegelian political philosophy argues, full participation in public life as a citizen depends on accurate recognition of one’s “humanity and uniqueness,” misrecognition of the lives of marginalized individuals and groups—such as stereotypes—materially hinder their access to the rights and privileges of citizenship. For example, the image of single Black mothers who use government assistance as “welfare queens” profoundly shapes welfare and health policy, as racist welfare reforms, legislative attacks on Planned Parenthood, and efforts to dismantle programs that disproportionately serve women of color amply demonstrate.

The majority opinion invalidating the current formulation of Section 5.4 of the Voting Rights Act reveals a similar sort of misrecognition. The crux of Chief Justice John Roberts’ opinion is the conviction that the “pervasive,” “flagrant,” “widespread,” and “rampant” racism that the 1965 Voting Rights Act was meant to redress no longer existed when the VRA was renewed in 2006, and doesn’t exist today. Rather, requiring pre-clearance of new voting laws for certain states but not others based on their history (and ongoing pattern) of disenfranchising voters of color is based on “40 year old facts having no logical relation to the present day” and unfairly seeks to “punish” those states for the past. Roberts insists, “History since 1965 cannot be ignored,” while simultaneously declaring history before 1965 irrelevant to the present day, despite the rash of draconian voter ID laws and district gerrymandering in the very states covered by Section 5.4 of the VRA.

What is apparently ancient history for Chief Justice Roberts and the majority is not even past for most Black Americans. Thus the ruling’s implication that “serious” racism is effectively over can be understood as an act of misrecognition. Implicit in the ruling is the sentiment, explicitly held by many whites, that Black people are being oversensitive or even deceitful when we talk about the continued relevance of racism in our lives. This is the seamy underbelly of the belief that “extraordinary” measures are no longer necessary to ensure the equal protection of people of color under the law—the corollary that when people of color agitate for such measures, we are demanding not equal access and opportunity, but undue “racial entitlements” (to use Justice Scalia’s own words about the VRA and affirmative action).

In other words, those of us who insist that race still matters are demanding more than our fair share, more than we’ve earned or deserve; we’re greedy, shiftless, and either deceived or lying about our lived realities. “Racial entitlements,” by this thinking, necessarily implies taking something that rightfully belongs to white people. When Chief Justice Roberts claims that states once covered by the VRA were being punished, and Scalia complains that “once Confederate state[s]” are “familiar objects of the [Supreme] Court’s scorn,” they suggest that racial aggrievement—if not outright malice—on the part of people of color makes whites the real victims of racial revenge fantasies.

Misrecognition matters because the power to decide and shape policy on issues of discrimination almost always rests in the hands of people who don’t experience (and often don’t or refuse to understand) the discrimination in question. Chief Justice Roberts, writing for a majority that was four-fifths white men, got to decide what constitutes reality for people of color with respect to racism—to decide that what most people of color say about our lives is in fact not true. As Harris-Perry writes in Sister Citizen, “to be a person of relative power and privilege viewing a person of less power and privilege” is inherently “a political act.”

This statement is as true for white liberals and progressives “viewing” communities of color as it is of white conservatives. In the weeks leading up to these rulings, I observed a typical but nonetheless disturbing discrepancy between white queers and organizations eagerly anticipating “major rulings” that only included DOMA and Prop 8, and not rulings on the VRA, affirmative action, Native sovereignty, or other issues that straight and queer people of color were also anxiously awaiting. Since these rulings, the response from mainstream LGBTQ organizations and media—dominated by white, cisgender, affluent voices—and their base has been at best tepid disapproval, if not disinterest.

This, too, stems from misrecognition—attitudes like “gay is the new Black” or “gay/LGBTQ rights are the civil rights issue of our day” that see racism as an abstraction or long dead concern. Ennui over attacks on voting rights fails to consider the most marginalized members of the community: LGBTQ people who are poor, trans, and/or of color. They not only fail to recognize that racism is very much still with us, they also fail to learn from the very movements they claim to be heirs to, and the continued, dedicated opposition these movements still face.

More Than Marriage

Advocates of marriage equality often draw parallels between one-time bans on heterosexual interracial marriages and current laws prohibiting recognition of same-sex marriages. The comparison is more apt than many realize. It seems all but inevitable that marriage equality will ultimately gain the national recognition and acceptance that straight interracial unions have, but in both cases it would be a grave mistake to see this as a cut-and-dried sign of progress towards equality.

Consider that theoretically widespread acceptance of interracial marriage (86 percent of the public and 78 percent of conservatives say they approve) exists alongside significant and dogged white opposition to measures to address severe racial disparities—say, in access to voting, and even more basic rights. Indeed, acceptance of interracial marriage is often wielded as evidence that racism is dead and such measures are no longer necessary (if they ever were). Some of the most strident conservative racism deniers, like Clarence Thomas and Ann Coulter, for example, have been or are in interracial relationships.

We’re now seeing the makings of a similar cultural disconnect on LGBTQ issues. Straight conservative politicians like Lisa Murkowski and Rob Portman have come around in support of marriage equality, and there’s good reason to believe that before long, supporting marriage equality will be a—if not the—conservative position on LGBTQ rights. Much as some white Americans, across the political spectrum, point to their approval of interracial marriage as disproving the reality of racism, it’s not difficult to see a day where straight “allies” might point to national marriage equality as proof that sexual minorities are no longer oppressed. (See this image, from 2004, by cartoonist Tony Auth, suggesting that women, people of color, and people with disabilities have already attained equality and that “gay marriage” is “next.”)

It would seem that marriage equality for queer folks and straight people of color alike, even with the considerable time and hard work necessary to secure it, is in some ways a more easily attained milestone than many even more fundamental rights. Extending legal recognition to interracial and queer couples is both subversive and, to quote Kent L. Brintnall, “expanding access” to what remains “an exclusionary institution” that orders family and sexuality in fundamentally conservative ways. It’s not a surprise that the “traditional” beneficiaries of marriage might simultaneously embrace the assimilation of new groups into this institution, while rejecting steps toward equality that require more radical challenges to existing power structures.

Conservatives continue to wage pitched battles at federal and local levels to maintain racial inequity in employment practices, education, housing, health care, and access to public accommodations. (Consider that in 2013, Paula Deen is being sued for, among other things, denying Black employees use of the same entrances and bathrooms as white employees!) Not coincidentally, access to decent shelter, work, health care, and public accommodations are the very issues that are most pressing for LGBTQ Americans—especially those who are poor, trans, and/or of color.

In other words, gay is not the new Black, and LGBTQ rights are not the single civil rights issue of our time. To think otherwise, as all too many do, is the same sort of misrecognition that shaped the Supreme Court’s VRA ruling: the notion that the work of the civil rights movement is done, and it’s time for LGBTQ people (mostly meaning white, cisgender, gay men) to take up their mantle. This misrecognition matters. Shrugged shoulders at rulings undermining the rights of people of color ultimately aids and abets efforts to undermine equality for all.

These assaults on voter rights have far-reaching consequences and implications, some of which we’ve seen just in the past week. The anti-choice omnibus bill rushed through the North Carolina state senate on Tuesday was made possible by extensive district gerrymandering that gave state Republicans 70 percent of seats in the legislature despite winning half the votes. This is just one of many regressive moves from North Carolina Republicans; they’ve also killed unemployment benefits, denied 500,000 North Carolinians access to Medicaid, and attacked a state law aimed at racial disparities in death penalty sentencing.

And it’s not just in the South; in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and elsewhere, the same state legislatures and governors leading the assault on voters’ rights are also pushing legislation that’s anti-choice, anti-public education, anti-worker, and anti-family. And they’re able to get away with it in part because of laws that hinder marginalized groups from voting in people who represent their interests—the same groups, incidentally, who are most likely to support marriage equality.

The seeming paradox of Justice Kennedy’s votes on marriage equality versus voting rights is no paradox at all. It’s reflective of how misrecognition of the reality of racism breeds complacency and indifference about stripping rights from the most marginalized citizens. And it’s an attitude that’s all too common in the LGBTQ rights movement—one we’ll have to address if we ever hope to achieve more than marriage.