How Did Emergency Contraception Get Excluded From VAWA?

By all accounts, the women’s rights advocates who fought to reauthorize VAWA never made EC a priority.

Women’s health advocates in the United States often pride themselves on leading the world toward greater gender equality. The celebration over S.47, the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 (VAWA), was no exception. Passage of VAWA required sustained and public fights to ensure it included protections for sexual minorities, immigrants, and Native women and access for individuals in need of post-exposure HIV prophylaxis treatment, which prevents possible HIV infection after unprotected sex.

Yet despite these considerable gains, the advocates failed to ensure that the bill fully protects rape survivors from the psychological and physical threat of unwanted pregnancy.

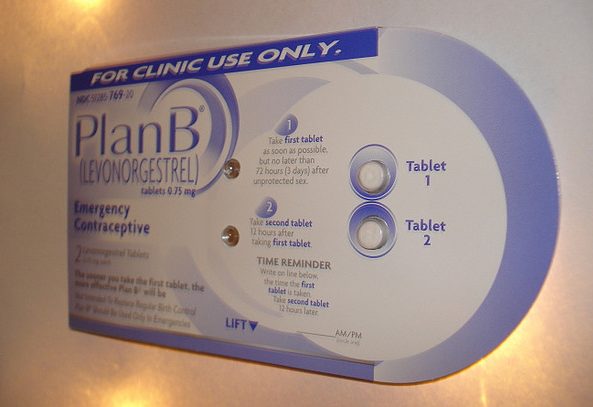

VAWA makes no explicit mention of emergency contraception (EC), also known as the morning-after pill, which is the only available method to prevent pregnancy after unprotected sex. The exclusion of EC from VAWA was not the result of opposition from the usual suspects. Rather, by all accounts, the women’s rights advocates who fought to reauthorize VAWA never made EC a priority.

In a conversation over email, a committee aide for Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT), the primary author of the VAWA reauthorization, told me the following: “The law requires states to make sure defendants get tested for HIV within 48 hours or they lose a certain percentage of money from one of the grant programs. Basically, the focus has always been around HIV, and emergency contraception was not an issue raised by any of the groups that the Chairman worked so closely with to reauthorize VAWA.”

I also talked to members of women’s health advocacy groups involved in passing VAWA to find out more about EC’s exclusion. None were willing to speak with me on the record. They all, however, confirmed what Leahy’s staffer said: The failure to include language on pregnancy prevention in the final version of VAWA did not result from fear that the bipartisan law would be rejected. Rather, EC was simply not a top priority for advocates, who instead chose to focus specifically on HIV prevention.

Several sources from these organizations also told me that ensuring access to EC for rape survivors was not significant enough to merit inclusion in federal legislation. They contended that states, not Congress, should adopt laws requiring EC in post-rape care.

The reality, however, is that state legislatures have largely failed to do this, and given the climate of current state EC laws, they cannot be expected to, either.

The majority of states have no requirements regarding the provision of EC to survivors of sexual assault. Only 16 states require hospitals to offer information and counseling about EC, and only 12 of those states (California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin) plus the District of Columbia also mandate that hospitals provide EC on-site to victims. (Hawaii’s Senate recently passed a bill requiring hospitals to dispense EC to rape survivors, but it has not yet become law.)

While I believe that most health workers do their best to offer compassionate post-rape care, lack of federal policy on EC provision leaves women in 34 states vulnerable to the whims of individual providers or hospital policies. As brought to light by organizations such as MergerWatch and Catholics For Choice, the increasing number of Catholic hospital mergers has greatly limited access to EC, even for rape survivors. In addition, pharmacists in several states refuse to provide EC on grounds of conscientious objection, a move that has been supported in federal court.

In addition, age restrictions for EC persist. Currently, only women and men age 17 and older are allowed to purchase EC over the counter. Forcing a teenage girl who has already been violated to seek a prescription or ask an older friend to purchase EC for her adds to her trauma. Age restriction policies are also unnecessary.

EC is safe and effective for all ages, and has been approved for adolescent use by both the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the American Academy of Pediatrics. However, Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius overruled the FDA in 2011, requiring adolescents under the age of 17 to present a prescription for EC. (Some state laws also require doctors to prescribe EC to adolescent rape survivors if necessary, but, again, these laws are few and far between.) Moreover, Sebelius overruled the FDA’s approval of EC as an on-the-shelf product, rather than a behind-the-counter drug.

Women and teens who need EC must therefore wait until pharmacies are open to buy the drug and also hope that the pharmacist will not object to selling EC. Because EC is only effective within five days of unprotected sex, unnecessary delays jeopardize a woman’s chance to prevent pregnancy, which is especially egregious if the woman was raped. Lack of EC services within VAWA therefore obstructs adolescents’ and women’s already limited access to EC at a time when they are most likely to need it.

Given all of these obstacles to EC access, especially for sexual assault survivors, it is notable that reproductive health advocates overlooked the possibility to incorporate language on EC into the reauthorization of VAWA. Indeed, very few advocates have critically analyzed VAWA, perhaps because many do not recognize the law’s exclusion of EC access and other pregnancy-related services.

For example, after the passage of VAWA, Chloë Cooney of Planned Parenthood Global published a commentary on Rewire urging international leaders to model resolutions after VAWA. She was specifically speaking to U.S. delegates at the UN Commission on the Status of Women (CSW)—which last week concluded a conference on violence against women—encouraging them to “leverage this victory and momentum for women’s rights and turn our attention to women and girls beyond our borders” by including “a commitment to expand access to sexual and reproductive health services” in CSW’s annual resolution.

Cooney perhaps did not realize that U.S. women’s rights advocates failed to include EC in VAWA. However, her call for widening access to reproductive health services was achieved when the international partners at CSW moved beyond the scope of VAWA by strengthening the commitment to expand EC access at the global level.

Less than one week after President Obama signed VAWA, delegates at CSW agreed to global commitments for eliminating and preventing violence against women. Despite opposition from conservative representatives, including those from Iran, Russia, and the Vatican, the majority of CSW’s 45 member states were able to push forward language that explicitly included post-exposure HIV prophylaxis and EC as well as safe abortion services (where legal), which were also excluded from VAWA.

Comparing CSW’s progress on reproductive health guidelines to that of VAWA is in many ways disheartening. Despite VAWA’s passage, we have at best a scattershot approach to providing survivors of sexual assault with the means of preventing pregnancy resulting from rape. The failure on our part to do so causes further violence to them and clouds any mission to help women “beyond our borders.”