No Clapping Matter: Antibiotic-Resistant Gonorrhea Is On the Way and We Are Not Prepared

For years, even those in the public heath community paid little attention to gonorrhea because it was easy to prevent, easy to screen for, and easy to treat—at least it was until now. Gonorrhea is caused by wily bacteria that has become resistant to all-but-one class of antibiotics and we don't have any others to throw at it. It's time to take start taking notice.

When I was a peer sexuality educator at UMASS-Amherst back in the early 1990s we used to joke about the fact that the only gynecologist on staff at the health center was named Dr. Daniel Clap. At the time it seemed hilarious that the man charged with prescribing our pills and diagnosing our sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) seemed to be named after one of the most common STDs. None of us knew why gonorrhea was called the clap (more on that later). In truth, apart from making the joke about the gynecologist’s name, none of us thought much about this bacterial infection that had been reduced a nuisance by the advent of antibiotics long before we were born. Sure, we stressed how condoms can prevent gonorrhea and how important it was to get tested for it because it often has no symptoms but in the workshops we led we paid far more attention to the “4-H club” because these diseases—HPV, HIV, Hepatitis B, and Herpes—were ones you might have to live with for the rest of your life.

We were not alone in our complacency around gonorrhea. The disease is easily prevented by condoms, easily tested for in STD clinics, and easily cured. HIV got attention for being potentially life threatening. HPV got attention for being so widespread and leading to cervical cancer. Gonorrhea was annoying but not much of a menace. Deborah Arrindell, Vice President, Health Policy for the American Social Health Association (ASHA), explained it this way:

“We think of gonorrhea as a funny infection—the clap—that doesn’t kill anybody. But the consequences of untreated gonorrhea are quite serious; infertility, increased risk of HIV, and a big impact on our national wallet…nothing to clap about there.”

Today, many in the public health community will admit that we collectively took our eyes off the ball because Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a very clever bug that has developed the ability to resist nearly all of the antibiotics that have been thrown in its path. It has steadily developed resistance to entire classes of antibiotics—as early as the 1940s it was resistant to sulfanilamides, by the 1980s penicillins and tetracyclines no longer worked, and in 2007 the CDC stopped recommending the use of fluoroquinolones (the class of drugs that includes Cipro, which we may all remember as the thing to stockpile in case of an anthrax attack). Today, the only class of antibiotics that remains effective are cephalosporins, but its susceptibility to these drugs is declining rapidly in the United States and other countries have already seen cephalosporin-resistant cases.

In February the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sounded the alarm about this growing threat and suggested that we need to change the way we screen for and treat gonorrhea in this country in order to respond to this wily germ. Last week, the World Health Organization (WHO) released a statement on this issue and, more importantly, a global action plan for stemming the spread of drug-resistant gonorrhea. As the resistant cases emerge, it is a good time to look at how we got here and what we can do to ensure that gonorrhea does not become a major public health threat.

Cephalosporin-Resistant Gonorrhea is Coming

Physicians in southern Japan saw their first case of gonorrhea that was less susceptible to the usual cephalosporin drug regimen as early as 1999. Sweden followed in 2002, England in 2005, and Norway in 2010. Many of these cases seem to originate in Japan. For example, in 2010 a Swedish man contracted gonorrhea from a woman he met on a trip to Japan. He required four times the standard dose of cefitriaxone to eradicate the bacteria. The following year, Japanese researchers announced that a sex worker in Kyoto was infected with a “highly resistant” strain that was cured only after multiple intravenous antibiotics. A similar case was reported in France.

Here, the CDC began the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) to monitor trends in antimicrobial resistance of gonorrhea in 1986. For this project, isolates are collected from the first 25 men with urethral gonorrhea attending STD clinics each month in approximately 28 cities in the United States. These isolates are then tested at one of four or five regional laboratories to determine their susceptibility to penicillin, tetracycline, spectinomycin, ciprofloxacin, ceftriaxone, cefixime, and azithromycin. The results of these tests have been used to assess the threat and change treatment guidelines numerous times as resistance to various drugs emerged.

There have not yet been any treatment failures in the United States but the occurrence of partial resistance to cephalosporins (meaning that the drugs only succumb to unusually high doses) has increased 17 percent since 2006. In addition, GISP tested 5,900 samples of bacteria from around the country and found that 1.4 percent of them had diminished susceptibility to cephalosporins.

In a February editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Gail Bolan of the CDC pointed out that the pattern of declining cephalosporin susceptibility is reminiscent of the emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant gonorrhea less than a decade ago. She concluded:

“We should anticipate the emergence of fit cephalosporin-resistant strains that can spread widely.”

Holes in the System

Gonorrhea is a widespread problem. With an estimated 600,000 new cases per year, it ranks as the second-most reported infectious disease in the United States. (Chlamydia is the first.) Still, until recently few people worried about it because both screening and treatment were easy and relatively inexpensive—important factors in the control of STDs.

For many years now, a patient who comes to an STD clinic is tested for gonorrhea using a sample of the patient’s urine and something called a Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (NAAT). These tests are simple to do and inexpensive to run and give you a lot of “bang for your buck” as it costs only $2 more to run a test for both gonorrhea and Chlamydia at the same time. If a patient tested positive for gonorrhea today, he or she would be given one injected dose of ceftriaxone (a cephalosporin) and would take home a seven day course of either azithromycin or doxycycline. If the health care provider was not set up to give an injection, the dose of ceftriaxone could be given orally instead. For the majority of individuals that would be the end of their interaction with a health care provider—most often there is no further tracking of the patient and no re-tests to ensure that the infection is really gone. Patients and providers alike simply assume the infection has been cured by the antibiotics despite the fact that gonorrhea is often asymptomatic. If a patient returned to the clinic with symptoms, it is likely that the health care provider would assume a new infection and start over.

This structure has been great in many ways because it has allowed for widespread screening and treatment which is one of the most effective ways to stop the spread of disease. As cases of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea emerge, however, it is becoming clear that there are problems with what we’ve done and holes in the system that will make it harder to address the disease moving forward.

The first problem is that we don’t test everywhere the bacteria are likely to live. The urine test is essentially a genital sample. It can tell whether an individual has gonorrhea in his/her urethra or cervix. But gonorrhea can also be spread to the throat and the anus during oral and anal sex. Men who have sex with men (MSM) are especially likely to have infections in these areas. A 2003 study of gay and bisexual men in the San Francisco area illustrates the problem. Participants were screened for Chlamydia and gonorrhea in their throat, urethra, and anus. The study found that if this population had only been given the urine test or urethral swabs, 53 percent of the Chlamydia cases and 64 percent of the gonorrhea cases would have been missed. Limiting screening to urine tests not only misses the opportunity to treat the individual in front of you but also allows these individuals to unknowingly spread the infection to others. Moreover, some public health professionals believe that years of undiagnosed infections of the throat is part of what allowed gonorrhea—which adapts by borrowing DNA from other bacteria and organisms—to become resistant in the first place. (Other reasons include over-use and misuse of antibiotics and anti-microbials both in treating medical problems and in our day-to-day life.)

The second problem is that while NAAT tests are inexpensive and simple, they don’t uncover all of the information we need. In order to determine if a patient is infected with a resistant strain, health care providers would have to swab the potentially infected area and use a culture to grow the bacteria. (I’m picturing the giant q-tip and red petri dish that Killer Kleckner, the nurse at Warensdorfer school, used to test us for strep throat.) Most providers—even those who regularly screen for STDs—are not set up to do this. From discomfort with the swabbing process, to a lack of training on how to culture, to a dearth of laboratories set up to run such cultures, to the transportation required to get the samples to the lab—many pieces of this puzzle are missing. As William Smith, executive director of the National Coalition of STD Directors (NCSD) explains:

“We’ve lost our ability to culture.”

I casually asked my pediatrician about how he tests for gonorrhea (because what mother who brings in her 21-month old for a cough doesn’t inquire about that) and he said he can do the urine test but isn’t set up to do cultures. He added that he might swab the urethra of teenage boy but would automatically send a young woman to a gynecologist. Moreover, he said that while he knows how to do culture by virtue of his age, he is pretty sure that individuals just a few years behind him in training would have never been taught that skill.

Surveillance is also a problem. Given that we now anticipate cases of gonorrhea that are resistant to cephalosporins, it is important to have a monitoring system in place that can catch these news strains quickly in order to ensure that they are not spread widely into the population. Our current system is chronically under-funded and not prepared to do this.

The biggest problem with how we do things now, however, is simply a lack of drugs that can work. And this problem is truly alarming because it’s just about gonorrhea anymore.

No Drugs In the Pipeline

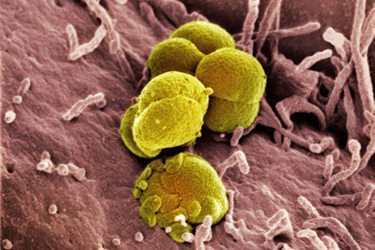

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is part of a group of bacteria know as gram-negative because they do not retain crystal violet dye in the Gram staining protocol. These microbes can cause serious diseases, including meningitis, pneumonia, and gonorrhea, as well as infections of the blood, urinary tract, and intestines. (E-coli, for example, are gram-negative bacteria). Such bacteria are increasingly resistant to most available antibiotics. As the CDC explains, “these bacteria have built-in abilities to find new ways to be resistant and can pass along genetic materials that allow other bacteria to become drug-resistant as well.” These are not the only bacteria that are becoming resistant to existing antibiotic—the infection known as MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) has gotten a good deal of media attention in the past few years. Like MRSA, gram-negative infections often occur in hospital settings. One major difference, however, is that there are new drugs—some approved in just the last few years—that are effective against MRSA.

In contrast, no new family of drugs to fight gram-negative bacteria has been introduced since the 1970s and there are no known trials in the pipeline. (After the post-9/11 anthrax scare the government did focus on development of new drugs but the results of this are not yet public.) Pharmaceutical companies have developed stronger drugs within the same family but that does not help once bacteria become truly resistant. A double membrane makes these bacteria harder to attack than those that are gram-positive but the real reason for a lack of new drugs seems to be less about the science and more about the money. Antibiotics are not money makers. Smith points out that antibiotics are relatively inexpensive and taken for a short period of time:

“Pharmaceutical companies are driven by profit and it is much more profitable to invest in the development of a drug someone is going to take for the rest of their life than something they are going to take for a week.”

In fact, a recent analysis found that at discovery a new antibiotic would have a value of minus 50 million dollars compared to a musculoskeletal drug which has a value of one billion dollars at discovery. The threshold for internal investment from drug companies is considered to be 200 million dollars. So it is not surprising that these companies are simply not investing their research and development dollars here. But it is a big problem and Smith believes that it’s time for the government to take action:

“When private enterprise isn’t doing what it needs to do to protect the public health, the role of the government is to step in. Thus far the government has failed to fulfill its responsibility to incentivize the development of good drugs.”

In a presentation for NCSD, Board Chair Dr. Peter Leone pointed out that antibiotics are unique because they are the only drugs that experience resistance that can be spread from person to person.

“If we don’t develop any new blood pressure drugs, in 50 years the drugs we have today will still work. If we don’t develop new antibiotics, we won’t have any effective antibiotics in 50 years.”

Leone argues that:

“In essence, antibiotics are public health community property.”

Progress has been made in recent weeks with the passage of the GAIN ACT, Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now Act of 2011. This legislation “seeks to increase the commercial value of antibiotics by extending the term of exclusivity granted to innovator drugs by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).” It also allows for a fast-track process for gaining FDA approval in an attempt to eliminate some of the uncertainty in the process which is often cited as a barrier to the development of new drugs. The Senate and the House both passed the GAIN ACT as part of the FDA reauthorization legislation at the end of May.

While we are waiting for the government and the drug companies to begin to develop new drugs, the CDC, the NIH, and WHO are working on new treatment plans that combine existing antibiotics to better attack the bacteria.

Change Is Needed But It Won’t Be Cheap

In addition to developing new drugs and treatment plans there are many things we can be doing to stem this looming health crisis. We need to scale up prevention education for both providers and patients as gonorrhea is one of the STDs that is most easily preventable using condoms. We need to develop state and local capacity to detect treatment failures and resistant strains. STD screening sites either have to become equipped to perform cultures or enter into partnerships with laboratories that have this capability. It might also mean that health care providers have to “test for a cure” —bring patients back post-treatment to ensure that the antibiotics worked. Public health professionals sometimes use the term “treatment-as-prevention.” The belief is that if we screen widely and treat those who are infected, they will not infect others. But this only works if the treatment is effective and with increasingly resistant strains we might need to start confirming that it was.

As Maryn McKenna, author of Superbug and a frequent writer on this topic, points out this might mean STD prevention and care is no longer inexpensive:

“… once you start bringing patients back and giving them additional and different tests, STD control becomes more costly. (That’s not even to mention the additional, distributed costs of developing new education efforts, surveillance systems or drugs.) In my read, that’s the real news in the WHO’s decision to sound a global alarm: a tacit admission that the era of cheap STD control may be over.”

The cost-benefit analysis is quite clear. Dr. Bolan estimates that without action, the incidence of gonorrhea could increase four-fold over the next seven year to 2.4 million new cases per year. This would likely result in 775 new case of HIV (because an active gonorrhea infection makes transmission of HIV easier) which would cost an additional $180 million dollars; 255,000 additional cases of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in women which would cost $585 million dollars and lead to 51,000 cases of infertility; and 50,000 cases of epididymitis (inflammation of the epididymis, a tube inside the testicles) which would cost $15 million dollars. The populations that would be most affected are blacks and men who have sex with men because these communities already have the highest rates of HIV and gonorrhea.

Still, in today’s environment in which the government is pushing for austerity even in the face of facts like these it’s hard to get more money. In fact, federal STD prevention funding has been cut by 5.8 million dollars from 159.6 million dollars in Fiscal Year 2005 to 153.8 million dollars in Fiscal Year 2012. In addition, 69 percent of states have cut funding to their STD programs since 2008. Smith argues:

“Given everything that we now know and the looming public health disaster, now is no time to be looking at cutting budgets on the federal, state, and local level for STD screening and treatment.”

Where’s the Public Outcry?

Every other day, my local news seems to warn me that germs are lurking everywhere—“the 10 germs in your car that make you sick, more at eleven.” I remember a few years ago when the Today Show did a week long expose using an ultraviolet light and cultures to determine what germs were lurking in hotel rooms, shopping carts, and diaper bags. Apparently, germs are everywhere and they can lead to respiratory issues and stomach aches. Uh oh. Despite this fascination with germs, I have yet to hear the mainstream media take up the rallying cry of drug-resistant gonorrhea. If this were strep throat or one of the dozen other childhood bacteria that I have run to Walgreens to cure in my own children, we might have the kind of public outcry we did over Bird Flu or Swine Flu but this has been somewhat quiet.

Arrindell points out that STDs have always gotten short shrift in the public discourse:

“As a nation we have a hard time talking seriously about sexual health. STDs, in particular, are considered a bad thing that happens to people who do bad things. We blame the victim.”

She added that:

“The disproportionate disease burden of gonorrhea is among African Americans and men who have sex with men which makes it even easier to ignore.”

Smith reminds us, though, that gonorrhea is just the tip of the iceberg—as time goes by more bacteria will become resistant to the available antibiotics. He pointed to the media coverage of recent cases of “flesh-eating bacteria” and notes that even there the issue of growing resistance is rarely brought up. He’s right. The stories I’ve seen about the Georgia college student who has thus far lost her left leg, her right foot, and both hands to a bacterial infection have all focused on her strength and her mood. None emphasizes that the “flesh-eating bacteria” she contracted when she fell of a zip line is called Aeromonas hydrophila (another gram-negative bacteria), that it has resulted in multiple amputations because it is not responding to any available antibiotics, or that there are no new antibiotics in development to help the next person who gets this bug. This seems like a bigger story to me than her daily frame of mind.

When I started discussing this article with a friend and began venting about how the public isn’t taking drug- resistant gonorrhea seriously, she said that everyone would pay more attention it made penises fall off. Well, it doesn’t quite do that but one theory of how gonorrhea got nicknamed “the Clap” is that early treatments involved doctors clapping hard on both sides of the penis, or worse, dropping a book on it, to clear the urethra of pus.

Perhaps the threat of going back to the painful old days will be enough to get policymakers, health care providers, public health experts, and drug company executives to begin working together to make sure that treatment options more sophisticated than clapping remain available.