Peace for the Abortion War, Part II

In a war for human dignity, you cannot ask opponents to split the difference.

Researchers in the Middle East

recently asked citizens what it would take to bring about peace in their

war-torn region. What they found might

surprise you. In what many in the West

might consider a "common-sense" offer, Palestinians would be asked to give up

their right to return in exchange for a two-state solution and a $10 billion

per year for 100 years. Yet both Israelis and Palestinians from across the

political spectrum rejected these options.

They would not sacrifice for peace.

But, if researchers suggested that the deal would come with

an official apology from Israel,

the whole picture changed. "Yes, an

apology is important, as a beginning," said Mousa Abu Marzook, the deputy

chairman of Hamas. When Benjamin

Netanyahu, a hard-line former Israeli prime minister was asked whether he would

consider a two-state solution if Hamas recognized the Jewish people’s right to

an independent state, he replied, "OK, but the Palestinians would have to show

they mean it." The researchers, Scott Atran and Jeremy Ginges, concluded in

their New York

Times editorial in January that "making these kinds of wholly intangible

symbolic concessions, like an apology or recognition of a right to exist,

simply doesn’t compute on any utilitarian calculus. And yet, the science says they may be the

best way to start cutting [through] the great symbolic knot [of Palestine] that is the

‘mother of all problems."

Imagine that: an apology. Not land, or money, or

sovereignty. A symbolic act of

recognition, an act that says I see you and I understand, can have more impact

than "material and quality of life matters" on the possibilities for

peace.

There are several things to learn from this. First, researchers did not survey the

hard-line leaders. They went to the

citizenry and asked them what they needed as conditions for peace. They raised the silent voices of those who

are most impacted by the conflict and presented their responses to the

leaders. Second, the researchers found a

way to get at the heart of what is at stake, beyond the concrete and typical

concerns about electricity, water, and the economy that are often the focus of

negotiations. Their research clarified

that for anyone involved in a conflict as long-lasting, deeply-felt and

consequential as the conflict in the Middle East,

the sacrifice of values and beliefs is considered unacceptable and could never

lead to peace.

If you have been following my posts on how to bring peace

to the abortion war here on Rewire, or have read Amanda

Marcotte’s critique

of my theory, you probably know where I am headed. In my posts I have proposed that the voices

of women who have had abortions should lead the dialogue about abortion in the United States,

not the current leaders of either side, as part of a strategy that I call

pro-voice.

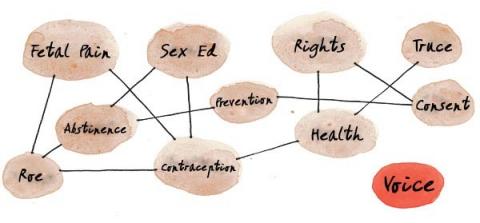

What I hope to convey now is that addressing abortion as a

matter of the heart and soul, rather than an issue of legal rights, can open up

new possibilities for peace. I will show

why compromise or politically-minded "common ground" solutions will not resolve

our war: the abortion war.

Many readers have questioned my use of the term "abortion

war" despite the fact that this terminology is a common cultural

reference. I understand their concerns. In conflict, the ability to define the debate

is part of the battle. Each side wants

to name the problem in a way that supports their goals, and hurts their

opponents. This is also true for the abortion war. If you ask people with a

range of political views what the "abortion war" is about, you are bound to get

very different answers. Some will say

that the war is waged to save innocent unborn babies, and others argue that it

was drummed up to drive a wedge between people who may otherwise agree. Still others say that the "abortion war" is

in fact a patriarchal assault on women, their bodies, rights and

sexuality. Fighting over the inherent

meaning, the root cause, of any given conflict is intrinsic to every

conflict.

Despite their disagreement, what people on different sides

of the issue have in common is a deep and fundamental belief that their fight

is not only important and justified, it is an opportunity and a privilege to

fight for what they believe. In essence,

this war isn’t about any one particular issue or right, it is about the

importance of who we are, our own human dignity, and the strength of our

conviction to fight on our own behalf.

I offer myself as an example.

I love a good debate. I love to be challenged to think in

new, critical ways and equally enjoy pushing others to do the same. I believe fundamentally in people’s inherent

goodness and in each person’s innate desire to strive to be better – and I

believe that we can harness that drive to improve all of our lives. And I have had an abortion, something I never

thought I would do, which has forever changed the way I look at the world. After my abortion, I came to understand the

value of the phrase "Don’t judge others until you have walked a mile in their

shoes" in a whole new way. I made a promise to myself to practice that value

every day of my life. My abortion was an awakening, a maturing, and a loss of

innocence, in the best and the most difficult sense of the term. Through direct personal experience with the

issue, in combination with my own personal passions and drive, I have found

this difficult debate over abortion to be an incredibly compelling place to put

all my experiences, values and beliefs into practice.

This war gives me something to do, something valuable and

something important. I do not want to

give up that sense of purpose in my life.

Neither do many of the women and men who have formed an identity as a

pro-choice or pro-life crusader and who have invested time, passion, and money

in their cause. That is why it is not

effective when outsiders call for an end to war through compromise. Even though both sides can probably understand

why "Americans are just tired of fighting over abortion" – as Jean Schroedel, a

political scientist at Claremont

Graduate University

told the Wall Street Journal

recently – crusaders won’t accept compromise as a political solution

because it demands that they sacrifice deep and profound parts of who they are

and they will not. They cannot. I won’t.

In a war for human dignity, you cannot ask opponents to

split the difference.

But, the fight over abortion has created a conflict of epic

proportions, attacks are personal and crusaders are hurt. Feelings of

disrespect, humiliation, and worse, misunderstanding, at the hands of opponents

make the need to be seen and heard, to be proven right, even stronger. This is how conflict works, how it escalates

and polarizes. With a deeper

understanding about the cycle of conflict, not only can we de-escalate and

transform the abortion war, we can take the steps that lead towards peace.

I believe that it is possible that as a society we may

arrive at a time when we are able to discuss the role government should play in

matters of sexuality, pregnancy and parenting without choosing sides through

the lens of war, without worrying whether a decision will strengthen or weaken

the political power of the pro-choice or pro-life movements. Peace does not mean that we all agree, but

that we focus our higher purpose on transforming the conflict instead of

feeding a war.

It is an interesting and unlikely time to plan for peace in

the abortion war. After years of political losses, there is a clear pro-choice

majority in all three branches of government and it is safe to assume that

peace is not in the political interest of winners. And yet, after a long and vicious battle,

wins are no longer as sweet for either side.

Warriors, while as committed and passionate as always, are tired. The

dramatic wins they hoped for have not occurred.

One side has not captured the heart and soul of all Americans. In fact, Americans have demonstrated

remarkable consistency on the issue – poll after poll demonstrates that most

people don’t like the idea of abortion very much, think it’s a pretty

significant emotional experience for women, and believe that it ends a human

life-of-some-kind, but are against making it always or mostly illegal, and hate

the idea of government regulating their private, personal lives.

Rather than continuing to invest in what is bound to be a

long, vicious slog on an issue that feels increasingly irrelevant to Americans

confronting grave threats to our planet and economy, we can invest in

transforming the conflict and start addressing matters of the heart. We can begin with an apology ("I’m sorry I

called you a baby-killer/vicious misogynist), a recognition ("The value you

place on life/rights is admirable"), or a symbolic concession ("I believe

abortion can be emotional for women/I believe in protecting the health of

pregnant women"). We begin by saying: "I

see you and I understand."

Leaders on both sides can and should be the first and set an

example for the rest. And, instead of

trying to recruit more Americans to the fight, when we already know they are

tired of it, leaders should invite Americans to join them: to grow our

collective understanding about the experiences of women who have had abortions

and to co-create a vision of care and support for women and their

families. Americans are great

problem-solvers – all we need is a little inspiration and someone ready and

willing to lead the way.

Together, we can and we should venture towards peace.

Related Posts

- Aspen Baker, The Pro-Voice Solution

- Amanda Marcotte, Peace through Pro-Voice?

- Aspen Baker, Peace for the Abortion War

This piece was also posted at Aspen Baker’s blog.