Boom! Lawyered: Standing Edition

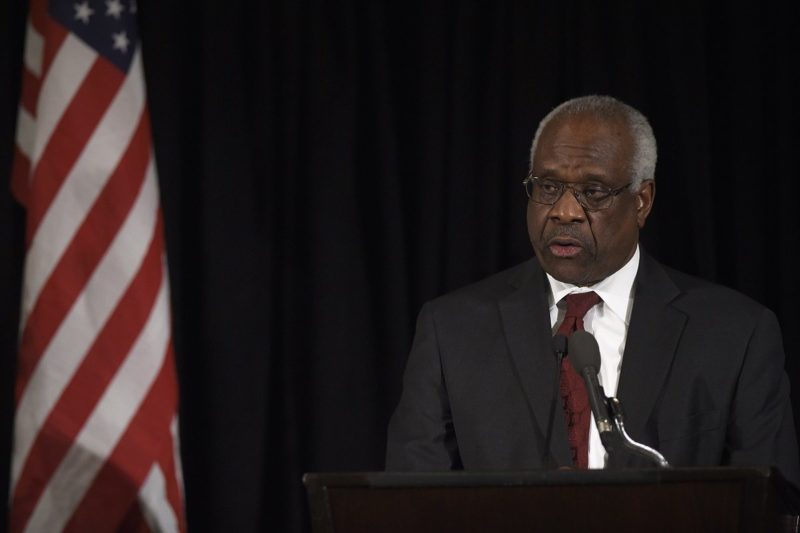

This week we’re going to talk about "standing," which is a term you may be familiar with, especially if you read Justice Clarence Thomas' complaint in his dissent in Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt.

Hello again, friends. Time to continue your informal education with another edition of Boom! Lawyered. This week is our 11th edition of Boom Lawyered, so let me take this time to encourage you to go back and read the first ten editions. By the time you do, you’ll practically be ready to take the Bar.

(No you won’t, and in any event, don’t take the Bar. Do something else with your life. The Bar is the worst. Trust us. Unless you’re already in law school, in which case the Bar is really not that bad and you’ll do just fine. We believe in you.)

But we digress.

This week we’re going to talk about “standing,” which is a term you may be familiar with, especially if you read Justice Clarence Thomas’ multipage complaint in his dissent in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt: He said that in multiple cases, the U.S. Supreme Court has wrongly ruled that doctors and clinics have standing to challenge laws that interfere with the constitutional right of women seeking abortion.

We’re also going to briefly discuss the “case or controversy” requirement and mootness because they are both important limitations on a federal court’s judicial power and are related to standing.

Article III of the U.S. Constitution grants federal courts the authority to resolve legal questions only if it is necessary to do so in the course of deciding an actual “case” or “controversy.” That means courts are not in the business of making legal pronouncements just for the hell of it. There needs to be a case between two interested parties who have asked a federal court to resolve a particular controversy.

And it’s not enough that a party asking the court to resolve the dispute has an interest in the issue. The party must also have “standing,” which requires three elements: (1) that the party has suffered a concrete injury; (2) that the injury can be fairly traceable to the conduct that the party is challenging in court; and (3) that the injury is likely to be redressed (or remedied) by a favorable judicial decision.

Now let’s set standing aside for just a moment and talk about mootness. The doctrine of mootness is intertwined with standing doctrine: Sometimes at the outset of a lawsuit, a party meets the standing requirement—she has suffered a concrete injury that can be traceable to the conduct that the party is challenging in court, and that can be remedied by a favorable judicial standing—but during the course of the litigation that injury disappears, rendering the lawsuit moot. Most of the time.

For example, if in Whole Woman’s Health Texas had repealed HB 2 on its own, Whole Woman’s Health’s case would have been moot, and the Supreme Court would have dismissed it on those grounds.

However, it’s not always cut-and-dried. In Roe v. Wade, Jane Roe filed a lawsuit in March 1970 asking a federal court to rule that Texas’ criminal abortion statutes were unconstitutional. By the time the lawsuit reached the Supreme Court in 1973, Jane Roe was obviously no longer pregnant. A favorable court decision would not have redressed her injury: Jane would no longer need an abortion. But this would always be the case with pregnant women trying to vindicate their rights, and the Court recognized this:

The usual rule in federal cases is that an actual controversy must exist at stages of appellate or certiorari review, and not simply at the date the action is initiated. But when, as here, pregnancy is a significant fact in the litigation, the normal 266-day human gestation period is so short that the pregnancy will come to term before the usual appellate process is complete. If that termination makes a case moot, pregnancy litigation seldom will survive much beyond the trial stage, and appellate review will be effectively denied. Our law should not be that rigid. Pregnancy often comes more than once to the same woman, and in the general population, if man is to survive, it will always be with us. Pregnancy provides a classic justification for a conclusion of nonmootness. It truly could be “capable of repetition, yet evading review.”

We therefore, agree with the District Court that Jane Roe had standing to undertake this litigation, that she presented a justiciable controversy, and that the termination of her 1970 pregnancy has not rendered her case moot.

This is a key point, so keep it in mind. Mootness. Remember that word.

In addition to the standing doctrine found in Article III of the Constitution, there is an important prudential, or judge-made, principle that federal courts frequently wrestle with: third-party standing. It relates to the ability of a plaintiff to represent the constitutional rights of third parties who are not before the court. Generally, a person may represent only her own interest in litigation and not the constitutional interests of someone else.

But courts will make an exception to this rule and permit a litigant to assert the constitutional interest of a third party not involved in the lawsuit if the litigant satisfies the requirements of Article III standing—injury, causation, and redressability—and if given the circumstances of the lawsuit, injured third parties would likely not be able to assert their own rights.

Pregnant people seeking abortions are the quintessential examples. And because of this, the Court routinely permits abortion providers to assert in court the rights of third-party women seeking abortions in addition to their own personal rights.

This vexed Justice Clarence Thomas in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt. In his dissent he complained that “the very existence of this suit is a jurisprudential oddity.”

“Ordinarily, plaintiffs cannot file suits to vindicate the constitutional rights of others. But the Court employees a different approach to rights that it favors,” he wrote. “So in this case and many others, the Court has erroneously allowed doctors and clinics to vicariously vindicate the putative constitutional right of women seeking abortions.”

Thomas’ implication is that the Supreme Court is full of abortion-loving justices who have not only found a constitutional right to abortion where there is none, but have also proven willing to dispense with rules that ordinarily would require women seeking abortions to sue on their own behalf, and not rely on doctors who provide abortions to sue for them.

This is, of course, nonsense.

Yes, the “capable of repetition but evading review” exception to the mootness doctrine provides an exception to the standing rule that would prevent pregnant people from ever vindicating their rights. (I told you to keep that word “mootness” in mind.) But as Cornell Law Professor Michael C. Dorf aptly pointed out, “[G]iven the private nature of the abortion decision, an exception to mootness will not give women adequate incentive to come forward to litigate their cases for the benefit of others, even if they are permitted to do so pseudonymously. Doctors who perform abortions, by contrast, do have such incentives, as repeat players.”

Litigation is a pain in the ass, and even if a woman is permitted to sue using a pseudonym—as Jane Roe did in Roe v. Wade—it is unlikely that a woman will think it’s so likely that she will need another abortion at some point in her life that she will decide to go through the hassle of suing to vindicate that future right.

In his dissent, Thomas provided a list of lawsuits where women had capably asserted their own rights in court, but not one of those cases was litigated in the last 20 years (and most were in the ’70s immediately after the Roe decision). There have certainly been none since 2011 when states embarked on this new effort to eliminate abortion by enacting statutes intended to chip away at abortion access.

It makes sense that doctors who satisfy the constitutional standing requirements—again: injury, causation, and redressability—should also be able to represent the interests of third parties not before the court when challenging the constitutionality of a particular abortion restriction. Then again, it probably only makes sense if you believe that women should have the right to choose what to do with their own goddamn bodies, which Justice Thomas clearly doesn’t.

But that’s a rant for another time.

So there you have it, friends! A quick explainer on standing.

You’re welcome.

Stay tuned: The next edition of Boom! Lawyered is just around the corner.