Welcome to the Gorsuch Court

John Roberts may still be the chief justice, but we are about to enter the age of the Gorsuch Court.

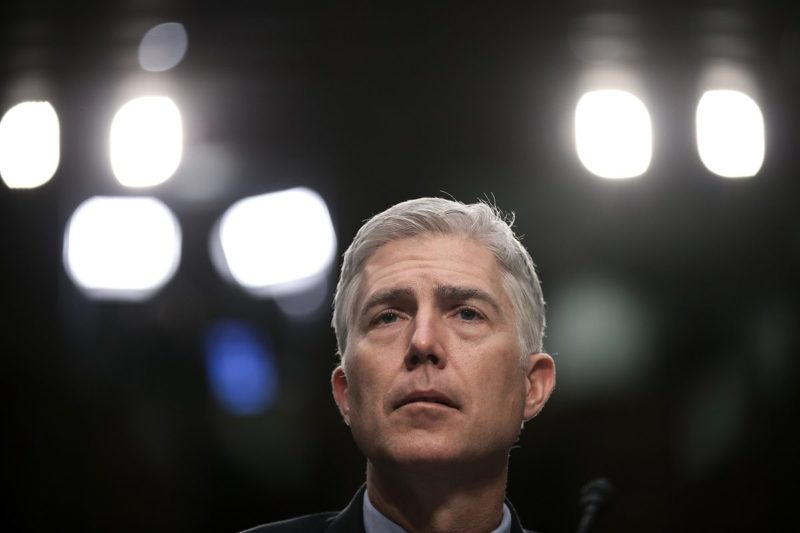

Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Neil Gorsuch is now Associate Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch. His nomination and confirmation is all but proof that conservatives’ long-game strategy of establishing an ideological hold on the federal judiciary has paid off.

As soon as President Donald Trump won the November election, it was clear that Republican Sen. Mitch McConnell’s political gamble of obstructing the nomination of Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court was devious but effective politics. It is all but guaranteed that the U.S. Supreme Court remains a conservative institution, which will protect business and religious interests at the expense of marginalized communities for decades to come.

Gorsuch’s confirmation doesn’t shift the political makeup of the Court the way Garland’s would have. But the fact that Gorsuch is a conservative replacing a conservative shouldn’t ease progressives’ concerns about his appointment, despite what commentators like former Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal argue. Yes, Gorsuch is a conservative ideologue in the mold of Scalia and thus will likely vote with the rest of the conservatives on the Court. But the combination of the politics that got Gorsuch confirmed to the Court, and the professional history that got him nominated in the first place, all but guarantees that it will not stay the Roberts Court for long.

John Roberts may still be the chief justice, but we are about to enter the age of the Gorsuch Court.

Gorsuch will forever and inextricably be linked to both congressional Republican obstruction and the never-ending swirling scandal that is the Trump administration. His confirmation is, in a way, the mirror opposite of the Roberts confirmation. Like Gorsuch, supporters of Roberts’ nomination focused on Roberts’ personality and reputation of building consensus among his colleagues. Those opposing Roberts’ nomination, though, pressed him on his record—and unlike Gorsuch, Roberts mostly responded with substantive answers. Roberts ultimately was confirmed in large part because, despite his conservative ideology, his promise to act as an “umpire” at least created the appearance that Roberts was independent from the Bush administration and would possibly hold it to account for any overstep. By contrast, Gorsuch’s refusal to separate himself from the Trump administration leaves open the very serious question: Just how independent from the president and his policies will Justice Gorsuch be?

Then there is the question of the influence Gorsuch will have on his fellow justices. There is a very real concern, for instance, that as a former clerk for Justice Anthony Kennedy, Gorsuch will pull Kennedy to the right in key areas of the law. He already did so as a Tenth Appeals Court judge in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, expanding significantly the ability of corporations to claim religious objections to regulations and and laws they do not like. He could, and likely will, do so on other cases as well. Consider, for example, the direct clash between claims of religious freedom, constitutionally protected free expression, and the rights of the LGBTQ community that is likely to get heard by the justices next term. There is the real possibility that legal challenges to the Trump administration’s Muslim ban will also land before the Court. Gorsuch will hear the very first test of the boundaries of the separation of church and state next week in oral arguments for Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer, an important case on the direct funding with state money of religious institutions.

With Gorsuch on the bench, just how important is the legacy of Kennedy’s “dignity doctrine,” which he has invoked in opinions lifting some discrimination against the LGBTQ community? Can Gorsuch get Kennedy to slide in favor of invoking religious imposition at the cost of individual liberty, as Kennedy did in Hobby Lobby? Kennedy didn’t want to answer the question of just how far religious imposition protections should stretch in opposing government regulations in the Little Sisters case last term. Instead, he avoided it by sending the string of cases challenging the religious accommodation process to the Affordable Care Act’s birth control benefit back to the appellate courts, including Gorsuch’s own Tenth Circuit. Those cases are still pending, providing another test of the kind of jurisprudential influence Gorsuch may be able to throw around on the Court.

These are, of course, not the only cases that should concern progressives. There are lurking and ongoing challenges to public union fees and sex and gender discrimination under civil rights laws, along with those trying to end the use of capital punishment and questioning the scope of executive administrative agency power.

And I didn’t even mention the possible challenges to abortion rights.

Gorsuch, and his time as Kennedy’s clerk matters, if his old-boys’-club confirmation hearing is any indication of how insulated the justices often are from the rest of the country. Will Gorsuch help keep Justice Kennedy in line with the other conservatives on these key issues, and roll back decades of civil rights advances in the process?

We don’t know yet.

Yes, Gorsuch would have likely voted as Scalia would have in almost every case that will come before the Court. But thanks in part to his personality, pedigree, and political history, Gorsuch may have more power and influence on the Court than Scalia ever did.