Boom! Lawyered: SLAPP Edition

The recent brouhaha over Kanye, Taylor Swift, and the Snapchat heard 'round the world is a perfect way to learn about Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPP), which are meritless lawsuits meant to bully a defendant and stifle speech.

Hello again, fellow law nerds! It’s time for another law lesson. Today, I’m going to discuss SLAPP lawsuits.

SLAPP stands for Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation. A SLAPP suit is a meritless lawsuit filed by a plaintiff whose only goal is to bully a defendant and make them less likely to exercise their constitutional right of freedom of speech.

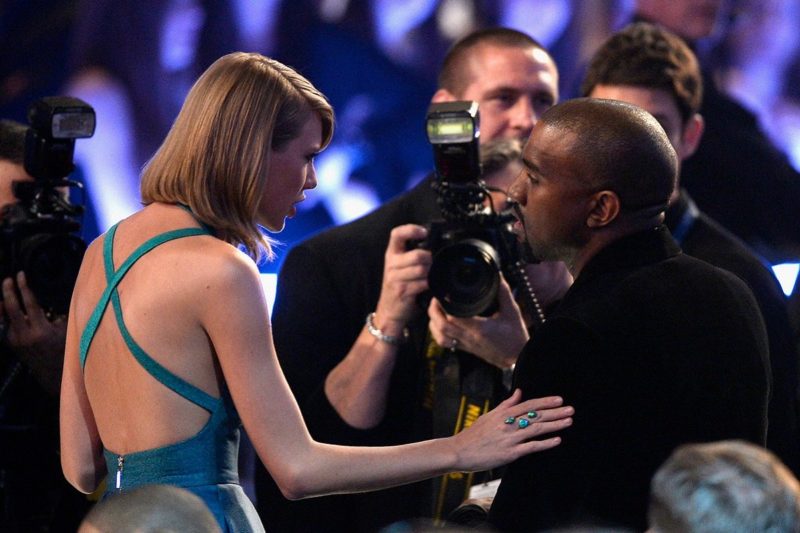

More than half the states in this country have anti-SLAPP statutes, which entitle a defendant to protection from such frivolous and malicious lawsuits. I’m going to focus on California’s anti-SLAPP statute, because that’s where I live and it is one of the most broad and protective anti-SLAPP statutes in the country. I’ll use the ongoing saga between Kanye West and Taylor Swift, which began in 2009 with West’s infamous “Hold Up, Imma Let You Finish” disruption at the MTV Video Music Awards, to explain how California’s anti-SLAPP statute operates.

In February of this year, Kanye West released a wildly bizarre video for his song “Famous,” featuring wax figures of various famous people—Donald Trump, Anna Wintour, Chris Brown, Rihanna, and yes, Taylor Swift—lying in bed together. (Honestly, “wildly bizarre” doesn’t even capture how fucking wildly bizarre Kanye’s video is.)

In West’s opening lines, he raps that he thinks he and Swift “might still have sex” because he “made that bitch famous.” At the time, Swifties (or whatever the hell Taylor Swift’s fans call themselves … Swiftheads? Swiffers?) were outraged.

Cut to six months later—on Sunday night, Kim Kardashian West released a Snapchat video of a phone conversation either she or her husband had recorded with Taylor Swift, in which Swift appears to give West carte blanche to use that line in his song. (Swift has since claimed that she gave approval for the “we might still have sex” line, but not for the “I made that bitch famous” line. Whether or not that’s credible is something that is currently being debated across social media and gossip sites.)

In the wake of the Snapchat reveal, Swift has threatened to sue the Wests. So for the purposes of this explainer, let’s say that Taylor files a lawsuit against Kimye (that’s Kanye and Kim) for defamation.

According to Taylor, she did not know that she was being recorded and Kanye never told her that he would call her “that bitch.” “Being falsely painted as a liar when I was never given the full story or played any part of the song is character assassination,” she said via Instagram.

Given that Taylor had originally claimed that she never heard the song and didn’t approve it, and Kim has, with her Snapchat, proven incontrovertibly that Taylor actually did hear and approve at least part of the song, Kimye might want to argue that Taylor’s lawsuit is an attempt to chill Kimye’s speech, and they might want to counter Taylor’s lawsuit by filing what’s called a motion to strike the complaint under the California anti-SLAPP statute.

The California anti-SLAPP statute protects “acts taken in furtherance of their right of petition or free speech under the United States or California Constitution in connection with a public issue”, meaning:

(1) any written or oral statement or writing made before a legislative, executive, or judicial proceeding, or any other official proceeding authorized by law, (2) any written or oral statement or writing made in connection with an issue under consideration or review by a legislative, executive, or judicial body, or any other official proceeding authorized by law, (3) any written or oral statement or writing made in a place open to the public or a public forum in connection with an issue of public interest, or (4) any other conduct in furtherance of the exercise of the constitutional right of petition or the constitutional right of free speech in connection with a public issue or an issue of public interest.

Upon filing the motion—sometimes called an anti-SLAPP motion—to strike a complaint under the anti-SLAPP statute, discovery in the case is immediately stayed. In other words, discovery grinds to a halt.

This is a bigger deal than you might think.

Normally, as soon as a plaintiff files a complaint, she can immediately begin discovery—including depositions, requests for documents, third-party subpoenas, and the like. Because the rules governing discovery in California permit discovery of almost anything even remotely related to the case, it permits an asshole plaintiff to harass a defendant by serving mountains of discovery requests and forcing a defendant to spend a pile of money to respond to them.

Another important thing happens when a defendant files an anti-SLAPP motion: A defendant automatically becomes entitled to recoup court costs and attorneys’ fees associated with the lawsuit, should the defendant win the anti-SLAPP motion. This is true even if the plaintiff gets cold feet and decides to withdraw the lawsuit. California’s anti-SLAPP statute really encourages plaintiffs to think long and hard before filing a lawsuit that might chill First Amendment free speech.

So how does a court rule on an anti-SLAPP motion?

In order to win the anti-SLAPP motion in court, Kimye would have the initial burden of proving that Taylor’s claim for defamation arises from “acts taken in furtherance of their right of petition or free speech under the United States or California Constitution in connection with a public issue.”

This should be a pretty easy hurdle to surpass. Kim’s release of the Snapchat video is speech, and given the brouhaha over Kanye’s video, and the fact that the entire kerfuffle involves three very public figures, an easy argument can be made that the video release is in connection with a public issue. After all, almost the entire nation was transfixed by the #KimExposedTaylorParty hashtag last weekend. (California courts construe “public issue” very broadly.)

Let’s say that the court finds that Kimye’s actions fall within the realm of activity that the anti-SLAPP statute was intended to protect. Taylor could still beat Kimye’s anti-SLAPP efforts if she demonstrates a probability of prevailing on the claim. (Because, again, the anti-SLAPP statute is intended to prohibit plaintiffs from bullying defendants in court by filing meritless claims, not meritorious claims.)

So the question becomes, does Taylor’s lawsuit have any teeth?

Well, let’s see.

Truth is a defense to a defamation claim. So assuming Taylor is suing for defamation because she believes her character has been assassinated by implications that she’s a lying liar who lies, she might lose the case: She originally claimed that she had never heard the song, but months later, as Kim revealed via Snapchat, it turns out that not only did Taylor hear the song, but she approved it and called it “tongue-in-cheek.”

Now, of course, Taylor has changed her tune: She claims that she was unaware that Kanye was going to call her a “bitch.” So her defamation argument isn’t that Kanye called her a bitch and she’s not actually a bitch, but rather that Kimye are telling the public that Taylor had agreed to be called “bitch” in the song and that in and of itself is reputationally damaging, given Swift’s squeaky clean quasi-feminist image and how demeaning she feels it is to be called “bitch.”

But months ago, Taylor’s complaint wasn’t that Kanye called her a bitch. She made a big doe-eyed stink about the release of the song in the first place, saying at the Grammys, “As the first woman to win Album of the Year at the Grammys twice, I want to say to all the young women out there: There are going to be people along the way who will try to undercut your success, or take credit for your accomplishments or your fame.”

So it seems like, initially, she was bothered by the very existence of the lyrics in the first place, claiming that she hadn’t heard it. Her initial beef wasn’t that she was bothered about being called “bitch.”

In any event, let’s assume the judge doesn’t believe Taylor’s belated claims. If a judge decides she’s unlikely to prevail on her claim, then Kimye will win their anti-SLAPP motion and the case will be thrown out.

And here’s the kicker: Taylor would have to pay Kimye all of their attorneys’ fees and court costs, which can be quite pricey. (Not for Taylor or even Kimye, obviously, since they likely take daily swims in their pile of gold coins, à la Scrooge McDuck.)

Absent an anti-SLAPP statute, the course of the litigation would play out very differently. Taylor could file a lawsuit for defamation and immediately begin discovery, dumping mountains of requests and subpoenas on Kimye.

In response, Kimye could file a motion to dismiss, but motions to dismiss don’t effectively combat malicious or frivolous lawsuits.

When faced with a motion to dismiss, a court must assume all the facts alleged in the complaint are true, and then determine whether those allegations in the complaint are enough to entitle the plaintiff to relief under the law. The court cannot look at evidence not contained in the complaint and must accept every allegation as true, even if the allegations are lies.

So, if Taylor alleges in her complaint that she unequivocally never heard the song before it was released and that Kanye never called her to ask for her approval, even though the Snapchat demonstrates that’s not true, Kimye would not be able to offer the Snapchat into evidence to show that Taylor is lying. Taylor would win the motion to dismiss, the case would proceed forward, and Kimye would rack up attorneys’ fees.

An anti-SLAPP statute would prevent all that.

So there you have it! That is, essentially, how anti-SLAPP statutes operate.

Anti-SLAPP statutes vary from state to state. You should check to see if your state has one, and if it doesn’t, you should ask your legislators to pass one. You never know when some angry plaintiff might decide to come for you and tie you up in court simply for exercising your right to free speech.